Flamboyant music icon and warrior of artistic independence, Prince passed away on 21 april 2016, but his work still burns bright. From Minneapolis to Paisley Park, he redefined the rules of sound, gender, and power. A look back at the meteoric path of an elusive genius, between rebellion, mysticism, and musical revolution.

Birth of a prodigy

On 7 june 1958, in a modest neighborhood of Minneapolis, a child was born who would never feel comfortable within the margins assigned to others. Prince Rogers Nelson, the result of a cross between the rough swing of jazz and the gentle fervor of gospel, grew up in a household where music was not a luxury but a way to breathe.

His father, John L. Nelson, was a demanding jazz pianist, a man of discipline and heavy silences. He composed under the name Prince Rogers, a pseudonym he would silently pass on to his son like a quiet prophecy. His mother, Mattie Della Shaw, was a singer in a rhythm and blues band, gentle and magnetic, but soon separated from the father. The child grew up between two worlds, two frequencies, two vibrations; and he learned how to make them converse.

The family home was often tense, sometimes broken. But Prince found a sanctuary there: the piano. At seven years old, he was already composing his own pieces. He didn’t play — he incanted. He didn’t rehearse — he translated. His ability to absorb and recompose what he heard went beyond learning; it was a kind of possession.

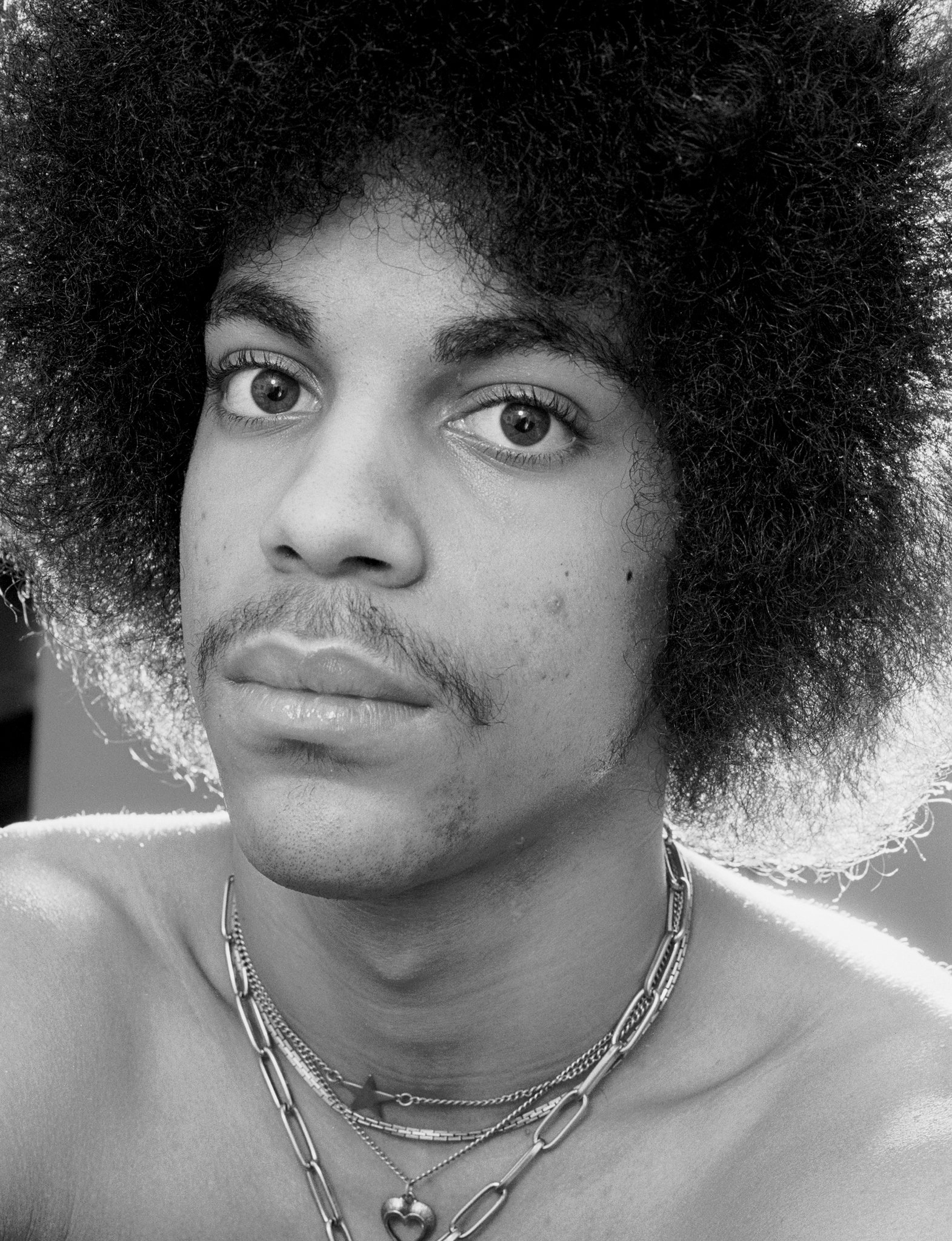

From childhood, he mastered guitar, bass, drums, keyboards. He didn’t learn instruments — he inhabited them. And very early, he knew he was different. Not just talented. Other. Strangely ahead. His body was frail, his voice high-pitched, his demeanor already androgynous. He was mocked. He withdrew. But his solitude became power.

At school, he was a misfit. But in the studios of Minneapolis, he was a silent prodigy, a rough diamond that a few producers began to notice. He moved from a teenage band, Grand Central, to more complex demos. He wanted to do everything himself. He demanded. He composed, arranged, produced. At 19, he signed a contract with Warner Bros.; with an unprecedented clause for such an unknown artist: total control over his music.

Because from the start, Prince rejected the idea of being “managed.” He didn’t just want a career. He wanted to shape a mythology. To be the absolute master of his sound, his body, his story. He hadn’t sung a single public note yet, but he was already fighting for his artistic autonomy.

The birth of Prince was not that of a singer, not even a musician. It was the emergence of an inner world, flamboyant, dense, unsettling. A world where genres were not borders but elements to fuse. A world where Minneapolis became the center of a sound empire. A world where a black, slender, secretive boy turned his vulnerability into creative strength.

The prodigy was born. But what he was preparing was not a career: it was an aesthetic revolution.

The rise to glory

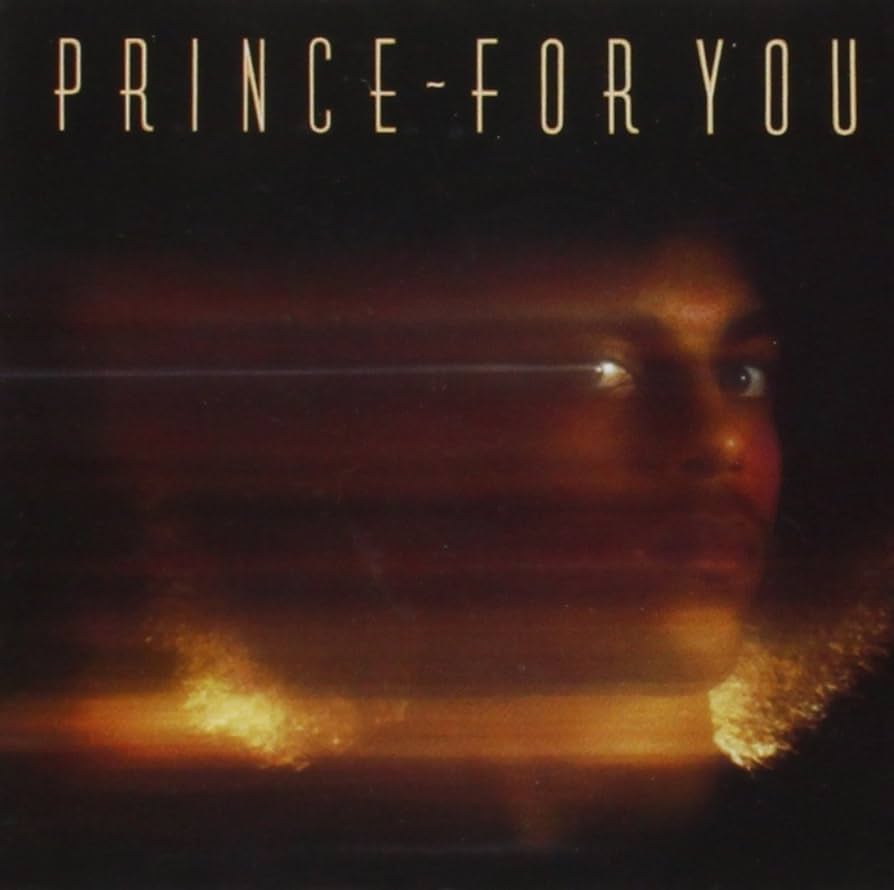

In 1978, at just 20 years old, Prince broke into history. His first album, For You, was both a declaration of independence and an artistic manifesto. Alone, he wrote, composed, arranged, produced, and played all 27 instruments heard on the record. A technical feat, but above all, a statement: no one would speak for him.

He was not yet a star, but already an enigma. On the cover, his fixed, defiant gaze challenged the industry. His style disturbed. His androgynous voice whispered and growled at once. His music slipped between genres like an elusive comet. Funk, soul, pop, rock: he didn’t choose. He fused them. He transcended them.

But it was in 1982, with the album 1999, that the world really began to listen. The record was an electronic firework. Drum machines and synthesizers shone like neon lights in the cold war night. The track 1999, a dancing end-of-the-world anthem, became a global hit. Little Red Corvette became one of the first tracks by a Black artist to receive heavy rotation on MTV. Prince shattered the racial walls of show business.

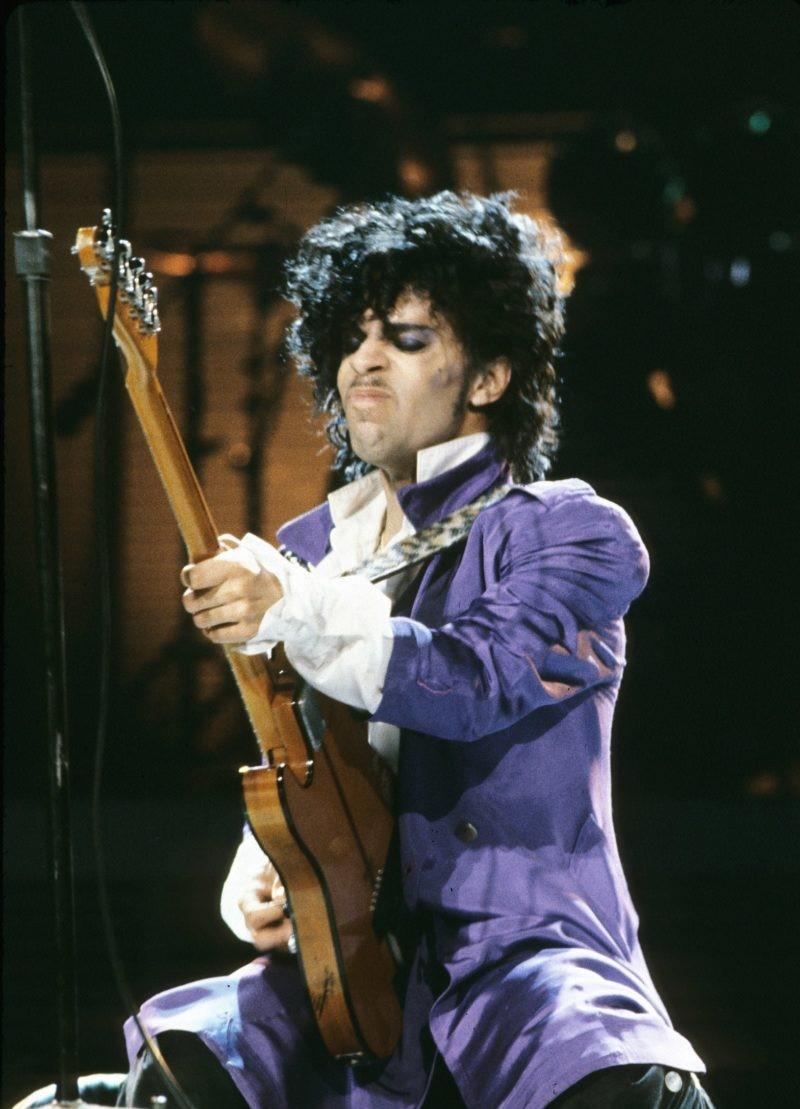

And then came 1984. Purple Rain. The album. The film. The myth.

Purple Rain was not just a success. It was a cultural earthquake. Upon release, the album exploded the charts. It stayed atop the Billboard for 24 weeks. The semi-autobiographical film portrayed a tormented artist in a rainy city, torn between light and shadow, between genius and collapse. Prince played The Kid, a fictional double of himself. He played, sang, bled. He wasn’t acting a role. He embodied a cry.

The audience was fascinated. Bewildered. Spellbound. The final scene, where he performs Purple Rain, is a rare moment of grace in musical cinema. A kind of communion between spiritual ecstasy and carnal urgency. Gospel met rock. Pain became transfiguration.

With Purple Rain, Prince was no longer an eccentric prodigy. He became a global icon, an androgynous sex symbol, a pop prophet who redefined norms of masculinity, Blackness, and success. He inhabited the stage as sacred ground. He seduced without compromise, dressed in lace, leather, ambiguity. He shocked puritan America — but conquered it nonetheless.

And yet, behind the glory, he remained elusive. Where others might have secured their image, Prince defied all expectations. After Purple Rain, he could have rested. He chose experimentation. He became even more radical. He understood that fame was not an end but a battleground.

Because for Prince, glory was never a gilded cage. It was an internal war zone. He didn’t want to be worshipped: he wanted to be free.

Purple Rain wasn’t the peak of his career. It was a launchpad for an even denser, more complex, more liberated body of work.

But in 1984, one thing was certain: the whole world finally knew what Minneapolis had always known. A genius had been born. And he would never settle for a throne; he would shake the palace walls.

The artist in search of freedom

Prince had achieved glory. But he soon understood that fame without control was just another form of slavery. In the 1990s, at the peak of his career, he entered into open conflict with his record label, Warner Bros. The issue: the right to own his music. He recorded, composed, created at a frantic pace; but the industry wanted to slow the tempo, control the releases, exploit the vein.

Prince didn’t want to be a product. He wanted to be a world. He refused to let his art be dictated by profit logic. So he made a radical, theatrical, highly symbolic gesture: he gave up his name. In 1993, he became Love Symbol; an alchemical combination of male and female, of note and cry, of identity and mystery. An unpronounceable glyph that journalists referred to, by default, as The Artist Formerly Known As Prince.

More than a marketing stunt, it was a holy war.

He painted the word “slave” on his cheek. He refused to say his own name as long as he was tied to Warner. He multiplied projects, sometimes released chaotically, but always driven by this obsession: to reclaim his sovereignty. This battle, waged solo against one of the most powerful majors, would inspire generations of artists to fight for the ownership of their masters, to reject the golden chains of the industry.

In this wake, he founded Paisley Park Records, his own label. Better still: he built Paisley Park, a utopian artistic complex on the outskirts of Minneapolis; studio, concert hall, creative lab. A kingdom for the free artist. A place outside of time where creation had no fences, no compromise.

Prince didn’t just want to make music. He wanted to redefine what it meant to be a Black artist, free and master of his own destiny. His fight went beyond contracts. It was about legacy. About memory. About a people too often robbed of their voice.

A prolific discography

In a world where artists are counted in singles, Prince built a world-work, dense, labyrinthine, decidedly unclassifiable. More than 40 studio albums, hundreds of unreleased songs, vaults full of demos and live recordings never published; his genius knew neither pause nor fatigue.

But it’s not the quantity that impresses. It’s the scope. The diversity. The depth.

In 1987, he gave the world Sign o’ the Times. A double album considered by many as his ultimate masterpiece. There, he blended political funk, haunted ballads, incandescent gospel, and electronic experiments. The title track, Sign o’ the Times, was a scan of the modern world: AIDS, nuclear war, urban despair. Prince became a chronicler of disaster, a prophet of fractures — but always carried by a belief in beauty.

He didn’t just entertain. He questioned. He disrupted. He healed.

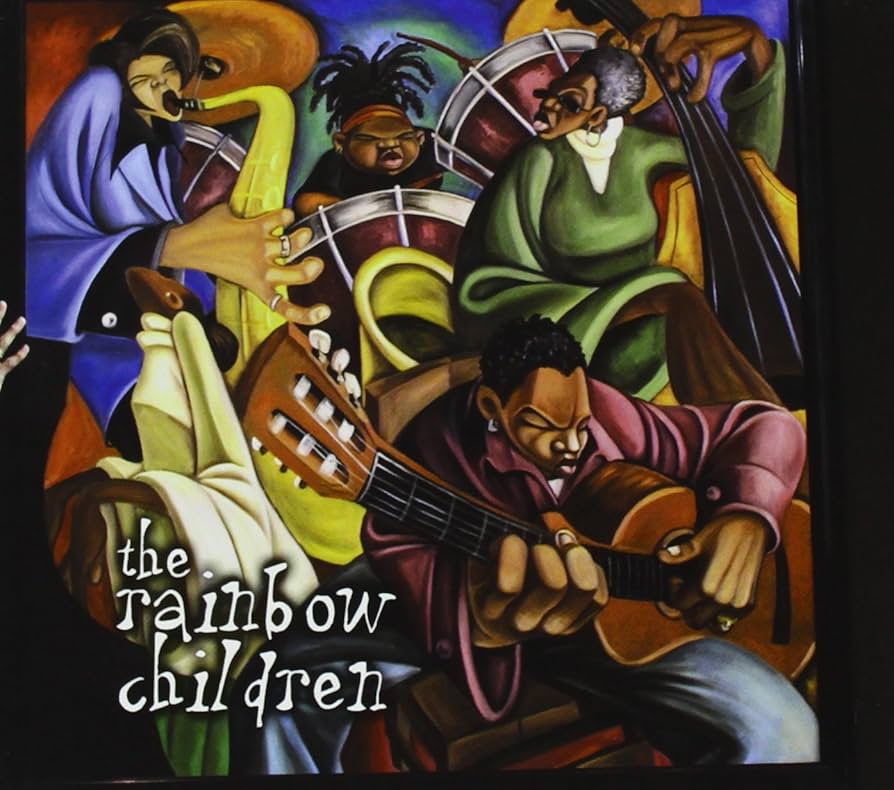

In the 2000s, as the music industry faltered, he released The Rainbow Children (2001). A spiritual, almost mystical album. Not commercial, difficult to access, but of rare intensity. There, he explored his faith, his vision of love, his reflections on race and power. The album sounded like a funk mass, where each track was a coded prayer, a call to awakening.

Prince crossed styles like an alchemist. He embraced psychedelic rock, flirted with jazz fusion, paid tribute to the gospel of his childhood — all while keeping the spine of his art: funk, that living, sweaty, organic matter he reinvented with every album.

Even his lesser-known projects (Come, Chaos and Disorder, Lovesexy, Art Official Age) bore his mark: a stubborn refusal to repeat himself, a drive to explore discomfort, to experiment in the shadows.

Prince wasn’t here to deliver what was expected of him. He was here to create what no one had yet dared to hear. He was the artist of excess, of overflow, of risk. His work isn’t consumed — it is crossed, like a blazing labyrinth, where each turn hides a revelation.

And in every note, one certainty remained: Prince didn’t want to be adored. He wanted to be heard.

On 21 april 2016, Prince passed away at the age of 57, leaving behind a vast musical legacy. His influence endures across generations, inspiring artists like Beyoncé, The Weeknd, and Janelle Monáe. His fight for artists’ rights and his avant-garde vision of music continue to resonate in today’s industry.

notes and references

Obituary – The Guardian, Prince: Musician found dead at 57 at Paisley Park estate, 21 april 2016.

Interview – Rolling Stone Magazine, The High Priest of Pop: Prince Talks Power and Music, 1985.

Unfinished autobiography: The Beautiful Ones, Prince and Dan Piepenbring, Random House, 2019.

ARTE documentary: Prince: le génie du funk, directed by Oliver Schwabe, 2022.

New York Times Archives, Prince’s Reign of Style and Sound, special feature published in april 2016.

Official discography: site princeestate.com, consulted in april 2025.

Critical biography: Let’s Go Crazy: Prince and the Making of Purple Rain, Alan Light, Atria Books, 2014.

Academic analysis: Sign o’ the Times and the Sonic Politics of Black America, Cambridge University Press, journal Popular Music, 2012.

Testimony – Sheila E., The Beat of My Own Drum, Harper Collins, 2014.

Archive statement – Warner Bros. Records, Prince name change and contract dispute, archives 1993–1996.

summary

birth of a prodigy

the rise to glory

the artist in search of freedom

a prolific discography

notes and references