Icon of jazz and priestess of the Black struggle, Nina Simone passed away on an April 21, leaving behind a voice that became a sword against injustice. Between sacred music and political anger, a look back at a burning, indomitable, unforgettable life.

Tryon, North Carolina; Where Revolt Is Born

Before being Nina, she was Eunice. Eunice Kathleen Waymon, born on February 21, 1933, in the small town of Tryon, at the foot of the Appalachians, in a Southern United States that barely hides its violence under a layer of segregationist courtesy. Tryon is a quiet town, the kind where Black people clean White people’s houses while children sing on Sundays at church. A corner of rural America where racism is a habit, not a scandal.

Eunice is the sixth of eight children, from a poor but dignified family, guided by a Methodist preacher mother and a failed artist father turned dry cleaner. Their life is punctuated by Sunday sermons, modest dinners, and hopes suspended on divine grace. It is in this context that little Eunice discovers the piano. At three, she climbs alone onto the stool, listens, reproduces. At five, she plays Bach as naturally as breathing. At eight, she is already too big for Tryon.

But talent is not enough when skin weighs heavily. Eunice wants to become America’s first Black classical pianist. A pure, immense dream, but already cracked by reality. The church becomes her improvised conservatory. She trains there, forges herself, refines a gift that escapes adult understanding. Very quickly, the entire town agrees on her genius. Money is collected, encouragements given. A White woman, her mother’s employer, becomes her patron. Another, Miss Mazzy, offers her free lessons every Saturday morning. It is at her home that the little girl hears Johann Sebastian Bach’s music for the first time. She is overwhelmed: “I thought I was going to faint, it was so beautiful,” she would later recount

But it is at twelve that the mask of the dream definitively cracks.

A recital. A solemn moment. She is on stage, ready to play. Her parents are there, seated in the front row. But White spectators demand they move back. They comply. Eunice sees, understands, refuses. She stops playing. The organizers panic. The room holds its breath. She will only resume once her parents have regained their original seats.

It is there, in the silent crash of that provincial hall, that Eunice Kathleen Waymon becomes more than a child prodigy. She becomes a conscience. An inner voice awakens, a noble, cold, irreparable anger: music will not serve to charm salons. It will be a sword. A mirror. A weapon.

That day, she learns that humiliation can infiltrate even the most sacred silences. And that one does not play to please a world that denies you the right to exist. One plays to rise again. So they hear. So they never forget.

And if Nina Simone was born later, it is here that the spark was ignited. In a dark hall in North Carolina, a Black child defied the White order with only dignity as her shield.

A refused pianist, a liberated voice

Eunice Kathleen Waymon never wanted to become a singer. Her dream was austere, solemn: to be a concert pianist. Not just any. The first Black classical pianist in America. She didn’t want to sing, she wanted to interpret Bach, Chopin, Debussy, with the almost sacred rigor demanded by the closed world of conservatories.

At seventeen, supported by White benefactors moved by her talent, she left North Carolina for New York. She entered the Juilliard School, elitist temple of scholarly music, where the future great performers of the Western world are shaped. There she discovered raw solitude, tense silence, the burden of being the only Black student in a universe designed for the White elite. But she held on. She clung. She trained for hours on end, to exhaustion. She played for Bach, for her mother, for History.

But the dream broke in Philadelphia.

The Curtis Institute, prestigious conservatory where she hoped to perfect her training, rejected her application. The sentence was cold, impersonal. The jury didn’t even bother to explain. Later, she would be told that she might not have had the “profile.” She knows, she feels, she does not forgive. She does not record this refusal as a simple failure, but as a betrayal. That day, it’s not just an institute that rejects her: it’s the entire institution that pushes her away. The little girl’s dream is buried without ceremony. She will not be the first Black classical pianist in America. Not because she failed. Because she wasn’t allowed to try.

So she goes down. Literally. From the heights of New York conservatories to the smoky bars of Atlantic City. There, in the nightclubs where people drink more than they listen, she plays to survive. The piano is no longer a sacred art: it’s a livelihood. But destiny sometimes has the cruel humor of legends.

One night, the Midtown Bar & Grill manager gives her an ultimatum: “If you don’t sing, you don’t play.” She protests. She’s not a singer. She’s a pianist. But she needs to eat. So she sings. Reluctantly. Instinctively. And her voice bursts forth. Deep. Vibrant. Ancient. A voice that doesn’t charm: it disarms.

This moment of constraint becomes a revelation. Singing, which she scorned as a betrayal of her ambitions, becomes a land of fire. She’s no longer the diligent little girl from Tryon. She is Nina. A creature shaped by disappointment, fed by humiliation, freed by necessity.

She takes a new name to hide her new life from her mother: Nina, an intimate little nickname meaning “little girl” in Spanish, and Simone, in homage to French actress Simone Signoret, whom she admires for her gravity, her raw elegance. Eunice Waymon disappears. Nina Simone is born in the shadows of clubs, between two drinks, between two solitudes.

On stage, she no longer just plays. She reigns. Her style is already there, in fusion: classical arpeggios to jazzy harmonies, gospel breaths to blues cries. She improvises as one rebels, mixes Chopin with Duke Ellington, spits truths in minor chords. She’s no longer just a musician. She becomes a voice. A presence. A war.

Rejected by the academy, Nina Simone creates her own school. A school of fire and pain, of rage and beauty. She sings because she was prevented from playing. And every note becomes a revenge.

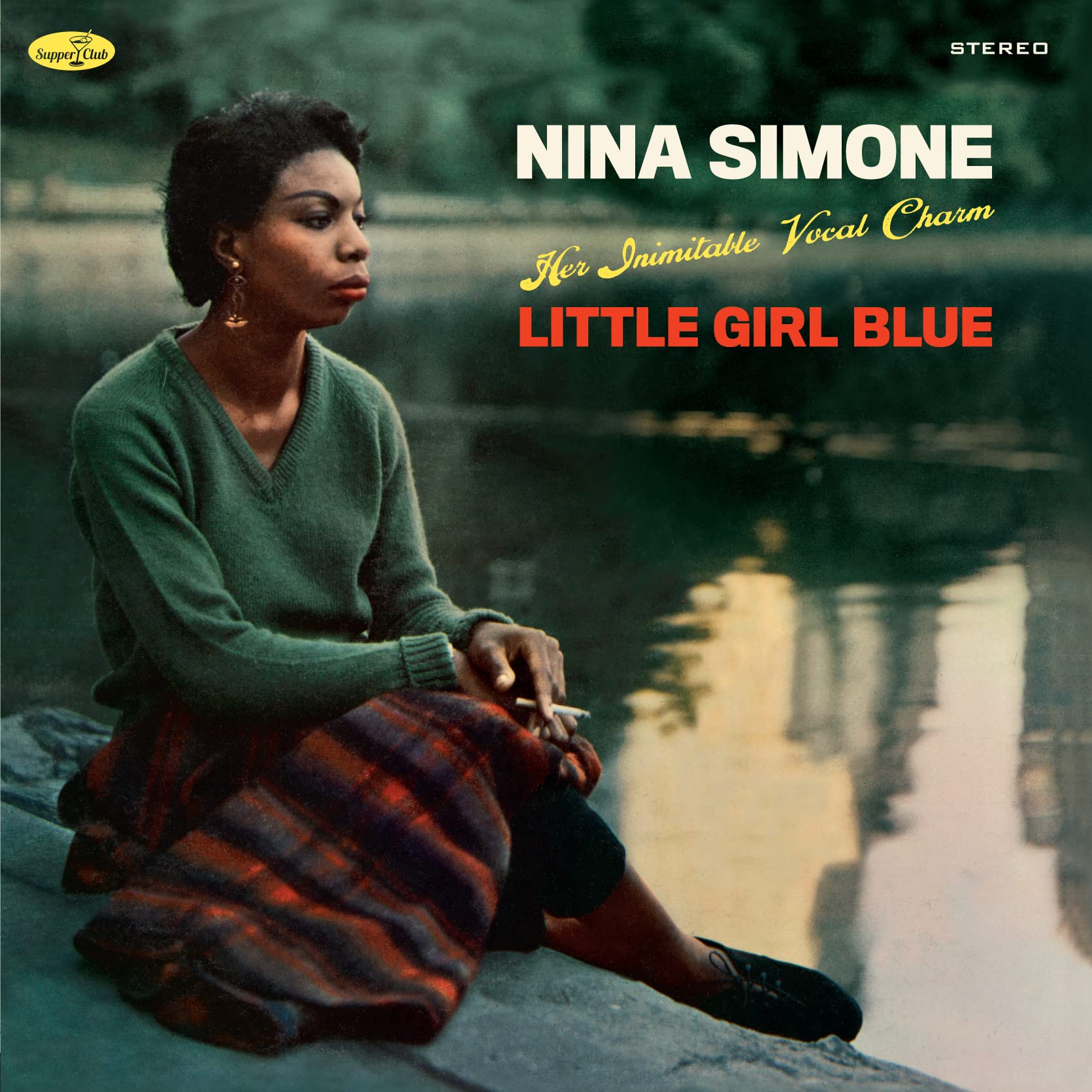

Little Girl Blue and the crash of the world

1958. The year the world discovers the voice of Nina Simone. A voice that doesn’t beg, that doesn’t cajole. A voice that doesn’t seek to please. It imposes. It cuts through. It shakes.

Her first album, Little Girl Blue, is recorded in a single take, in an almost anonymous New York studio. She is still little known, hastily signed by Bethlehem Records, a label more concerned with profit than posterity. She plays there, of course, but she also sings. By default. Out of necessity. And one of these songs, I Loves You, Porgy, a cover from George Gershwin’s opera Porgy and Bess, will change everything.

She had first sung it for a lover. She performs it like a stifled prayer, with a fragility that contrasts with her strength. It’s not a vocal demonstration, it’s a whispered confession, that of a Black woman addressing love with the terror of a beaten child. Her version touches the heart of the American public, enters the Top 20, climbs unexpectedly, seeps into the radios. And all at once, Nina Simone is no longer an unknown pianist from jazz clubs: she becomes a budding icon.

But Little Girl Blue is not just a commercial springboard. It’s a manifesto.

From the very first measures, one senses that something is offbeat. The piano is treated as in a concert hall. The voice, deep and dense, is that of a woman who refuses infantilization. Nina Simone follows no rulebook. She blends hymns, blues, Debussy’s harmonies, gospel flights. She covers My Baby Just Cares for Me with a tender swing, but the tension remains, like a clenched jaw behind the smile. Each song seems to dwell in an in-between: neither quite jazz, nor fully classical. It’s a music in unstable balance, like the society around her.

And that, the industry doesn’t know how to sell it.

Too sophisticated for popular radio, too Black for classical circles, Nina Simone escapes categories. She refuses to choose between conservatory and cabaret, between contemplation and rage. So she creates her own language. A bastard and sovereign music. A borderland music. Where Johann Sebastian Bach converses with Billie Holiday, where lamentations become orations, where classical arrangements coil around Black anger.

Little Girl Blue is not the story of a sad girl. It’s that of an artist who refuses resignation. The “little girl” is not docile. She clenches her teeth. She hides her fire. She prepares the explosion.

And fate’s irony has it that, despite this triumph, Nina will gain no financial benefit from this record. She sells the rights for $3,000, without a solid contract, without a lawyer. Bethlehem takes advantage, reissues, exploits. She, she watches, furious, powerless. A slap, one more. But she learns.

She learns that in this world, talent is not enough. That being Black, female, demanding, means being systematically dispossessed. So she will toughen up. She will sharpen her music like a weapon. Never again trust those who hand over contracts with a smile.

Because Little Girl Blue is not only the beginning of a career. It’s the end of an illusion. That one can be brilliant and protected. No, Nina Simone will be alone. Alone, but free.

Mississippi Goddam: the activist is born

Spring 1963. Birmingham, Alabama. A Baptist church is blown apart by an explosion. Four Black girls (Denise, Carole, Addie Mae, Cynthia) are killed. America expresses faint outrage. One more. One tragedy too many, in a South that will stop at nothing to defend its white supremacy. For Nina Simone, this is not just a crime. It is a point of no return.

She is in her living room, in New York. Her face closed. Silent. When she hears the news, she does not cry. She does not pray. She gets up. She walks to her piano. And there, like an earthquake held back for years, the words, the notes, burst forth:

“Alabama’s got me so upset

Tennessee made me lose my rest

And everybody knows about Mississippi Goddam.”

It is no longer a song. It’s a slap. A charge. A call to arms.

Until then, Nina Simone had contained her rage. Her music already spoke of shadow, pain, humiliation. But she had never, until Mississippi Goddam, let her anger explode head-on. There, for the first time, she names the states. She names the crimes. She names the hate. And she softens nothing. The word “Goddam” (a blasphemy in puritan America) cracks like a verdict. It is a condemnation without appeal. She spares no one.

This turning point is irreversible.

The classical pianist, the bar singer turned jazz star, becomes an activist. Radical. Incandescent. She abandons all pretense of artistic neutrality. From now on, every song is a manifesto.

Every concert, a platform. She befriends Lorraine Hansberry, playwright and brilliant voice of Black Feminism, who urges her to politicize her art. She reads James Baldwin, debates with Stokely Carmichael, admires Malcolm X. She rejects the path of conciliation advocated by Martin Luther King. She no longer believes in peace. She believes in rupture.

«America is a rattlesnake. I no longer extend my hand to it. »

She says it, sings it, hammers it in. She wants Black schools, Black banks, Black hospitals. She dreams of a separate, reinvented country. Nonviolence, to her, is a luxury reserved for the dominant. And when she takes the stage, it is no longer to entertain. It is to denounce. To rally. To ignite.

Mississippi Goddam is banned from many Southern radio stations. Some stations return it, snapped in two, to the label. But the song spreads anyway. It becomes an anthem. A war cry in the form of a cursed cabaret tune. Because Nina hasn’t changed the form: she remains a pianist, she plays in swing. But the content, it has turned to lead. A bomb disguised as a jazz number.

And this is only the beginning.

On Pastel Blues, she covers Strange Fruit, Billie Holiday’s poem on lynchings. On Let It All Out, she recites Images by Waring Cuney, a text on the erasure of Black women. Then comes Four Women, a tragic tableau of four African-American female stereotypes; the mammy, the mulatto, the prostitute, the rebel. Each character, a wound. Each voice, a condemnation. Censored on certain radios, the song provokes outrage. And admiration.

But it is To Be Young, Gifted and Black that becomes the ultimate anthem. Written in tribute to Lorraine Hansberry, gone too soon, the song is an ode to Black youth. It is neither lament nor prayer. It is declaration. Affirmation. Resurrection.

Nina Simone then becomes what white America cannot stand: an educated, angry, free Black woman. A woman who refuses to beg. Who looks her audience straight in the eyes. Who says: You will fall like flies.

She doesn’t want to be a star. She wants to be useful.

She is not the soundtrack of her era: she is its breath, its shiver, its clamor. Black rage set to music. Black beauty, held high like a fist.

And behind every note of Mississippi Goddam, lies a silent promise: You will not silence us anymore.

Exile as remedy

There are artists who leave their country to conquer the world. Nina Simone, she leaves not to get lost. In 1970, she slams the door on America as one leaves a toxic lover. She vanishes into the night, alone, without warning, leaving behind husband, house, debts and disillusionment. This departure is not a whim. It is an act of survival.

The United States suffocates her. Fame exhausts her. Activism consumes her. Her husband and manager, Andy Stroud, a former policeman, has become her domestic jailer. He beats her. Controls her finances. Manipulates her contracts. She, the untameable priestess on stage, is chained in her own home. So she flees. First to Barbados, that piece of land where the sea seems to wash away pain. She has an affair there with Prime Minister Errol Barrow. A burning passion, but without a future.

Then silence. The real kind. The deep kind. The kind that frightens as much as it soothes.

At the call of Miriam Makeba, she settles in Liberia with her daughter Lisa, for a suspended, almost unreal time. She no longer gives concerts. No longer composes. She breathes. She is silent. Africa becomes a refuge, a matrix. But it is also a mirror. Because there, she understands that her fight is not only American. It is Black. Universal. Visceral.

An errancy through Europe follows. Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, then France, which will become her final anchor. In Paris, she plays in cramped clubs, before audiences rediscovering her, or not knowing her at all. At Les Trois Mailletz, at New Morning, on the banks of Île Saint-Louis, she sings as one whispers to ghosts. France, though proud to welcome Black exiles, does not know what to do with a woman so fierce, so fractured, so divine.

She lives in a modest apartment in the South, in Bouc-Bel-Air, then in Carry-le-Rouet, where she will spend her final years. Far from studios, far from spotlights. She lives without luxury, but without chains. She writes, she meditates, she sometimes composes. Away from turmoil, she regains her verticality.

But it is on stage that Nina truly finds her breath again. There, despite fatigue, solitude, undiagnosed bipolar disorder, she rises. Her body is heavier, her gaze harder. But her fire has not faded. It crackles, hidden in every silence, in every hesitation. And sometimes, it explodes.

Montreux, 1976.

She is back. That night, it’s not a concert, it’s a ceremony. She arrives dressed like a fallen queen, upright like a priestess. From the very first seconds, she stops the music to scold a spectator who is talking. “Respect the music.” It is not a request. It is an order. The audience, frozen, obeys.

Nina begins to play. Bach slips into blues. Her voice trembles. Her hands waver. She laughs, then cries. She addresses, she pleads, she attacks. She sways between pain and dignity. This concert is a theater. An exorcism. She sings her fear, her solitude, her refusal to die slowly. She no longer tries to charm. She tries to stay standing.

« I never wanted to sing again. But here I am. Because I need you. »

That night, she does not sing for the audience. She sings in front of it. To remind herself she exists. To stitch herself back together. Each note is an attempt to gather her scattered pieces.

And Europe, slowly, begins to understand. Montreux will become mythical. Parisian clubs will fill again. Festivals, documentaries, tributes will come, belatedly. But Nina Simone no longer needs applause. She has transcended glory.

Exile did not break her. It stripped her. Freed her from the fake, the futile, the flashy. It made her bare, but essential.

She lost America. She won her freedom.

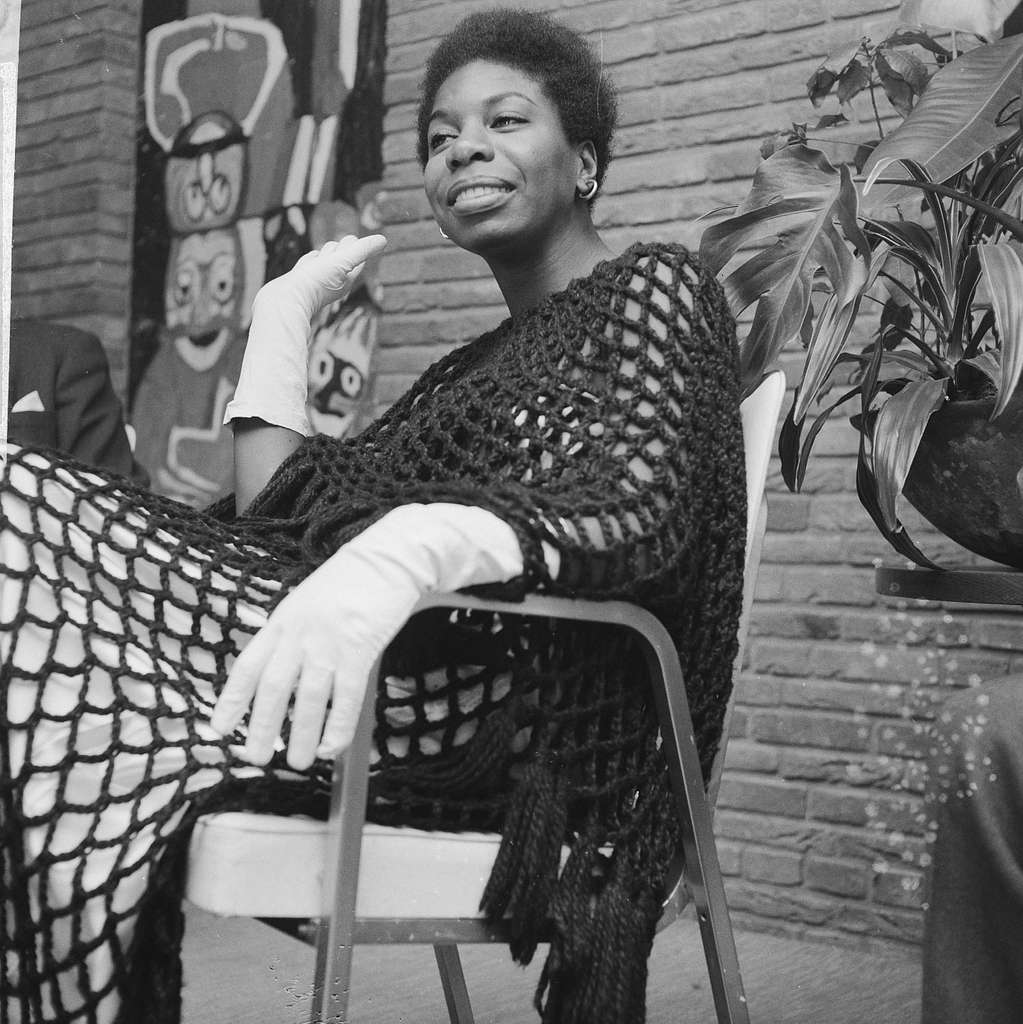

The sacred fire of a Black conscience

Nina Simone was not born to please. She was born to speak. To cut into the flesh of silence. To slap sweet lies with rough truths. In a world that demanded Black women be docile, seductive, grateful, she chose to be the opposite: untameable, uncomfortable, incandescent.

She was not a diva. She was a priestess, a prophetess with temples marked by solitude and struggle. Every public appearance, every concert, every silence even, became a ritual. She entered the stage as one enters a trance: tense, inhabited, almost elsewhere. She sat at the piano as one enters war. A sacred war, from which no one (not even herself) emerged unscathed.

What many ignored (or pretended to ignore), is that this extreme intensity was nourished by deep suffering. Bipolar disorder, diagnosed late, long repressed. Her loved ones saw her collapse, scream, go silent for days, then be reborn in moments of pure grace. Her music was crossed by this duality: the sublime brushed up against the abyss, softness gave way to scream without warning.

But Nina Simone never apologized for her excesses. She embraced them. More than that, she brandished them. Because what the world called “madness,” she called raw truth. She knew the cost of lucidity, memory, anger. She refused to anesthetize them.

And she disturbed. Deeply.

She refused to be locked into any narrative. Neither that of the melancholic genius, nor that of the wise icon. She rejected the very idea of a role model. Even among her allies, she provoked. She criticized the rap movement, accusing it of destroying the image of Black women, of diverting Black anger into misogyny rather than toward the system. She didn’t mince words:

« They make young people believe women are whores. That’s not what it means to be Black and free. »

She didn’t embrace late flattery either. Honorary awards, official tributes: she looked down on them. She mistrusted white America wanting to sanctify the woman it had first tried to silence. She refused to be “reclaimed,” even by those who claimed to love her. She didn’t want to be a statue. She wanted to remain a flame.

“I wasn’t made to be a legend. I was made to burn.”

At every concert, she put her soul on the line. She didn’t sing to entertain. She sang to shake, to awaken, to purify. She sometimes interrupted her songs to harangue the audience. She looked spectators in the eye, demanding their silence, their attention, their respect. Music was her temple, and she reigned there alone, sovereign, proud, in pain.

She never stopped dreaming of a Black world, autonomous, dignified, built on the ashes of the old white world. She didn’t want to assimilate. She wanted to overturn, rebuild, reinvent. This dream, she carried it like a torch, even when everything around her was falling apart.

Nina Simone didn’t live a career. She lived a struggle. A long procession through fire, shame, beauty, ecstasy, and downfall. This sacred fire, she never put it out. And if it sometimes burned those who came too close, it was because it was real. Burning. Impure. Human.

And even today, one hears it in her silences, in her sighs, in the sting of her notes: that fire does not ask to be admired. It asks to be passed on.

An incandescent legacy

On April 21, 2003, in the peaceful light of the Mediterranean, Nina Simone passed away in Carry-le-Rouet. She was 70 years old. Breast cancer had slowly eaten away at the body that had given everything. But her death is not an end. It is a continuation. A shedding. Because Nina Simone does not disappear: she spreads.

Her voice, that hoarse fire with the accents of prayer, continues to resonate in the veins of contemporary culture. She is no longer just a singer. She has become a vibration. A Black wave that crosses generations, genres, continents.

Kanye West samples her in Blood on the Leaves, twisting her version of Strange Fruit into a hip-hop fresco as furious as it is desperate. Lauryn Hill honors her with every sung syllable, like a spiritual daughter carrying the legacy of her rebellious mother. Beyoncé cites her name like a mantra, a tutelary Black star. John Legend, Alicia Keys, D’Angelo, Andra Day, so many contemporary artists name her plainly: without Nina, we wouldn’t be here.

But Nina Simone’s legacy goes beyond music. She haunts images. She appears in ARTE documentaries, Netflix films, poetic montages on HBO, in the verses of Sonia Sanchez, Maya Angelou, Claudia Rankine. Her life becomes an object of fiction, reflection, recitation.

She has entered the global Black memory as a secular saint.

And yet, this legacy is anything but appeased. It burns. It still disturbs. Because what she left behind is not a catalog of hits, but a living conscience. A way of resisting through art. A way of saying no, in full light. She showed that music could be a weapon, an archive, a political statement. That singing, for a Black woman, could be an act of self-determination.

She didn’t sing to seduce the crowds. She didn’t want trophies or pantheons. She wanted to be heard. Understood. Remembered.

“I want my people to know they are young, gifted and Black.”

That simple verse, turned anthem, still echoes in marches, schoolbooks, slam stages, in the mouths of mothers teaching their children dignity.

Nina Simone reversed the gaze. She forced cameras to film differently. She demanded that stories change narrators. She exposed the violence of forgetting, and opposed it with a burning memory.

Because Nina Simone’s true legacy is this: a fight against erasure. She refused to let history keep being written without her people. She refused to be digested, whitened, neutralized. She imposed history in its Black version, rough, beautiful, and imperfect.

And even today, in every silence broken, in every Black woman who dares to stand tall, in every child learning to play Bach with the dark skin of their past, there is a spark of Nina Simone.

No, she is not dead.

She has become unforgettable.

Summary

- Tryon, North Carolina; Where revolt is born

- A refused pianist, a liberated voice

- Little Girl Blue and the crash of the world

- Mississippi Goddam: the activist is born

- Exile as remedy

- The sacred fire of a Black conscience

- An incandescent legacy