Written in the solitude of a Birmingham cell on April 16, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr.’s letter is far more than a plea for civil rights. It is a political prayer, a moral weapon, a cry of truth. Sixty years later, it still resonates with undiminished urgency. Nofi offers you a vivid and immersive rereading of this foundational text, at the crossroads of history, memory, and contemporary conscience.

Letter from an american cell

Birmingham, stage of a moral revolution

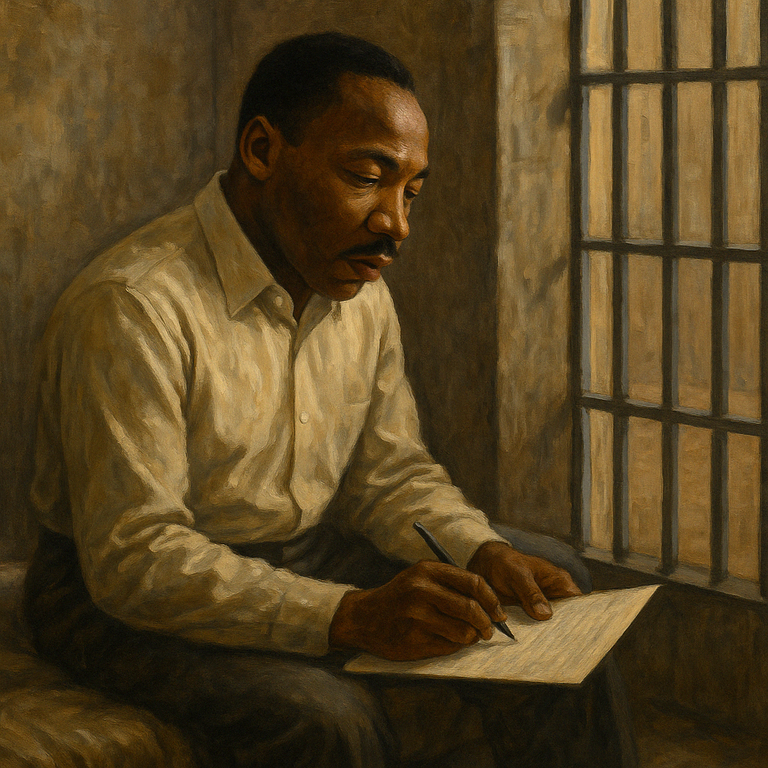

An April 16. A black man. A bare cell. A borrowed pen. Words like stones.

It was in the moist, cruel embrace of a municipal prison in Alabama that Martin Luther King Jr. composed one of the most radical texts of 20th-century American thought. The year was 1963. The country already vibrated under the tensions of its own paradox: preaching democracy in Vietnam while denying equality in Birmingham.

This was not a fiery manifesto. Not a sermon. It was a letter. But not just any letter. It was not addressed to tyrants or judges. It was addressed to “fellow clergymen,” white, moderate, well-meaning, who criticized him (not for his ideas) but for his methods. To them, King moved too fast. He disturbed the peace. He disrupted order. He forced the hand of History.

So he responded. Not to convince. But to lay down, in black and white, the duty to disobey injustice.

Birmingham, 1963: The city where even the air was segregated

One must understand Birmingham to understand this letter. One must feel the fear that prowled there, the brutality institutionalized as public policy, the segregation etched into the sidewalks. At the time, it was one of the most racist cities in the South. It was nicknamed “Bombingham” because of the dozens of bombings targeting Black homes that dared challenge the status quo. None were ever solved.

When the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) launched their campaign in April 1963, their goal was not only to challenge segregation: they wanted to expose the American lie. They knew the South would not change without being confronted, and that only direct (nonviolent but inevitable) confrontation would force dialogue.

On April 12, King was arrested. His crime? Demonstrating without a permit, despite a court injunction. His response: a letter. Scribbled in the margins of a newspaper, continued on scraps of paper provided by a sympathetic Black guard, finalized on a notepad smuggled in by his lawyers.

The radicalism of patience

The accusation from the white pastors was deaf but polite: “your actions are untimely.” Translation: wait. King, with explosive patience, deconstructed this injunction. He wrote:

“Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

He cited Socrates. He referenced Niebuhr. He even invoked Jesus as an “extremist for love.”

But he did more: he told stories. He dove into the daily scenes of Black humiliation. He spoke of his daughter to whom he had to explain why she couldn’t go to the amusement park. Of Black mothers who were never called “Madam.” Of “Whites Only” signs that lacerated the soul. Every word was evidence. Every paragraph, an indictment of institutional violence.

This letter was America’s trial, written from within America itself.

The art of disobedience, or when direct action becomes a political prayer

The beauty of the Birmingham letter is that it turns disobedience into liturgy. A gesture as thoughtful as it was spiritual. For Martin Luther King Jr., nonviolent resistance was neither blind rage nor rebellious spontaneity. It was science, faith, strategy. It had its method, its stages, its asceticism.

He wrote clearly: every nonviolent campaign involves four steps. Rigorous fact-gathering. Negotiation attempts. Self-purification — the moral preparation for expected violence. And finally, direct action. Not rushed. Not for spectacle. But to force society, confronted with its contradictions, to open its eyes.

Birmingham was not improvisation. It was a theater of reality, where injustice was laid bare, and power forced to face itself.

Creating tension without hurting

In this passage lies an essential idea. King did not fear tension. He demanded it. He even redefined its nature. It was not the violent tension of hatred or physical confrontation. It was mental, moral tension, like the kind Socrates provoked in his disciples. A fertile friction. A salutary discomfort.

“I do not fear the word ‘tension,'” he wrote. “There is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension necessary for growth.”

A crisis was needed for consciousness to emerge. Illusory peace had to be troubled to hope for real justice.

Patience as a moral trap

The white pastors accused King of moving too fast. The refrain returned: “wait.” As if merely not dying was enough. As if politeness should outweigh freedom.

King, in one of the letter’s most powerful flights, dismantled this injunction. He listed the invisible wounds, those seeping into daily life: humiliating signs, averted gazes, distorted first names, the impossibility of explaining injustice to a child. He made the weight of silence, contempt, and internalized marginalization palpable.

And he cut through it:

“Justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

There lies the modernity of his thought. He demanded not just rights — but their immediate realization. Because to wait for equality was still to obey the oppressor’s calendar.

The radicalism of love and the politics of the just extreme

At the heart of this letter lies a masterful theological and political pirouette. A reclaiming of semantics. For his detractors (white pastors, moderate journalists, respectable figures) not only called King impatient. They also accused him of extremism.

And here, King smiled. He picked up the gauntlet. He seized the word (“extremist”) and turned it inside out. Not to reject it. But to sanctify it.

Being an extremist… but for what?

“Was not Jesus an extremist for love? Was not Thomas Jefferson an extremist for liberty and equality?”

King, in just a few lines, blurred the markers. He placed his actions in a sacred lineage — that of prophets, founders, martyrs. He refused comfortable centrism, the kind that condemned the violence of the oppressed more forcefully than that of the oppressors.

The problem, he wrote in essence, was not extremism. It was the moral content of that extremism. There are extremists for hate, injustice, and power. Why not be extremists for love, truth, and freedom?

Through this rhetorical coup, King shattered the illusion of neutrality. He exposed the complicity of silence. He asked all of us: what kind of extremism are you witnessing?

The fundamental divide: White moderation vs. black suffering

What emerges throughout the letter is deep disappointment. Not toward declared racists, whose hatred was overt. But toward the “moderate friends,” those who, while claiming to support equality, refused confrontation, called for calm, postponed revolt to tomorrow.

Perhaps that was King’s deepest wound. He believed in dialogue between believers. He extended his hand to white churches. And it was precisely these voices, these hands, that left him alone in his cell. Worse: who reprimanded him for shouting too loudly.

“The greatest stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate…” he wrote.

The shock is brutal. The clarity, total.té totale.

Notes & References

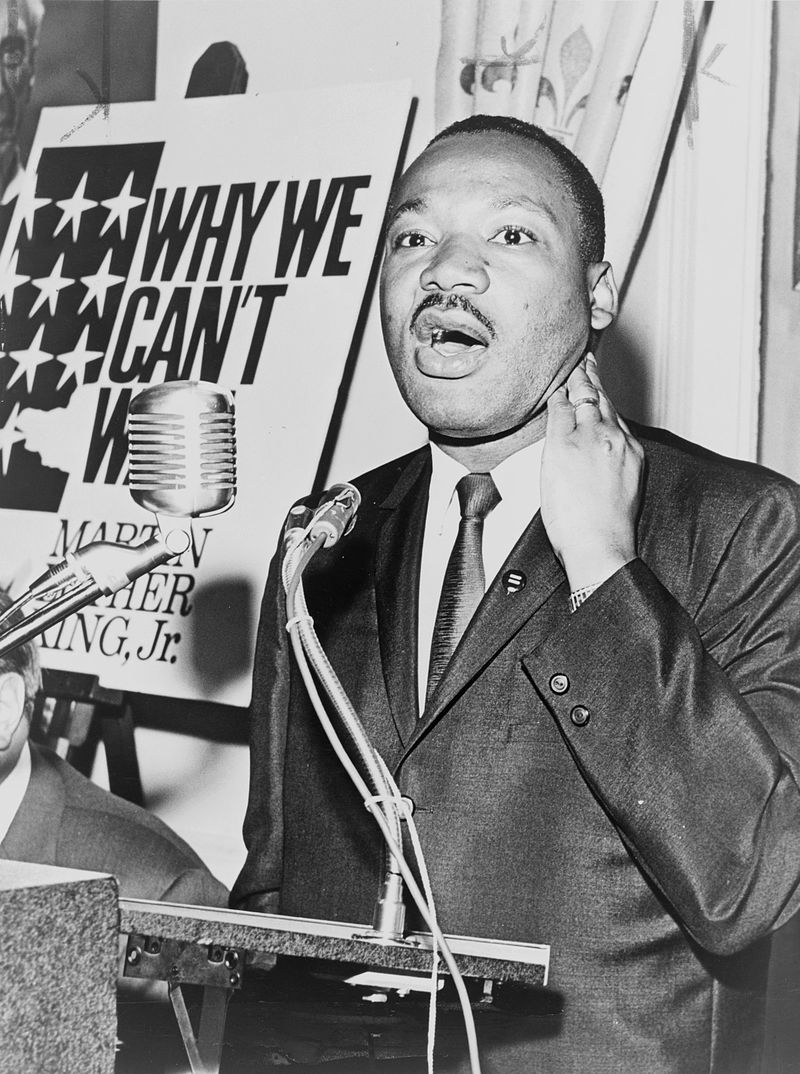

- Martin Luther King Jr., Letter from Birmingham Jail, April 16, 1963, published in Why We Can’t Wait, New York, Harper & Row, 1964.

- “A Call for Unity,” statement by eight white Alabama pastors, Birmingham News, April 12, 1963.

- The Birmingham Campaign, coordinated by the SCLC and ACMHR, aimed to expose segregation in public spaces through nonviolent direct actions.

- Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC): organization co-founded by Martin Luther King Jr., playing a central role in civil rights mobilizations from 1957 to 1968.

- Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), founded by Fred Shuttlesworth, coordinated local resistance to segregation in Birmingham.

- Key quotation: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” — MLK.

- Theoretical figures cited in the letter include Socrates, Thomas Jefferson, Reinhold Niebuhr, and even Jesus, blending philosophy, theology, and natural law rhetoric.

Summary

- Letter from an American Cell

- Birmingham, Stage of a Moral Revolution

- Birmingham, 1963: The City Where Even the Air Was Segregated

- The Radicalism of Patience

- The Art of Disobedience, or When Direct Action Becomes a Political Prayer

- Creating Tension Without Hurting

- Patience as a Moral Trap

- The Radicalism of Love and the Politics of the Just Extreme

- Being an Extremist… but for What?

- The Fundamental Divide: White Moderation vs. Black Suffering

- Notes & References