Once a slave, now an icon of British high society, Julius Soubise embodies the complex journeys of Black lives in 18th-century Europe. Between elegance, satire and scandal, a look back at a forgotten, flamboyant, and unsettling figure.

Julius Soubise: from chains to gilded salons

Around 1754, in the sugar plantations of Saint Christopher (St. Kitts), in the British Caribbean, Othello is born. Son of an enslaved Jamaican woman, he has no rights and no mapped-out future. At the age of ten, he is “acquired” by Royal Navy captain Stair Douglas and shipped to England. His name already rings like a Shakespearean omen.

But in London, an unexpected turning point: Othello becomes Julius Soubise, the extravagant protégé of the highly influential Duchess of Queensberry, Catherine Douglas. She manumits him, renames him with a noble French name, and introduces him to the most exclusive circles of British aristocracy.

In 18th-century England, a free Black man, skilled in fencing, a gifted horseman, dressed in silk and powdered wigs, does not go unnoticed. Trained by Domenico Angelo, fencing master to Europe’s crowned heads, Soubise becomes a teacher of riding and fencing… to a duchess. And in aristocratic circles, he is called: “le Prince noir”, or sometimes, “Prince Ana-Ana-maboe”.

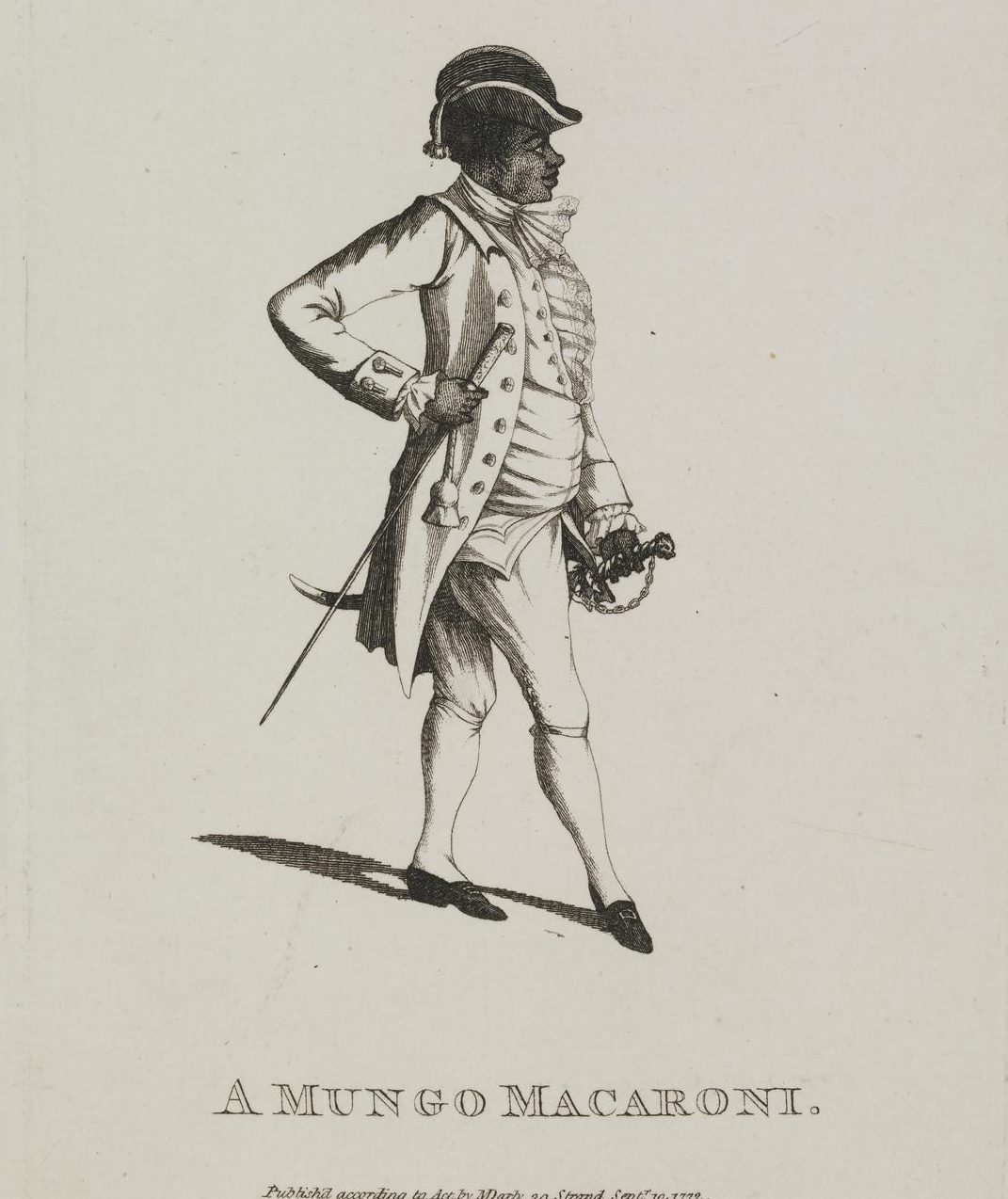

Admitted into London’s elite clubs, he embodies the unsettling image of a Black man who is too visible, too free, too refined. He also becomes an actor, musician, speaker, trained by the famous David Garrick. Soubise fascinates, unsettles, amuses, inspires. Caricaturists seize upon him. The image of the “Mungo Macaroni”, a biting satire blending racism and classism, is born.

In 1772, a satirical drawing published by Matthew and Mary Darly depicts him as “Mungo”, a grotesque Black servant character from a comic opera. This “Mungo Macaroni”, a mix of dandy and servant, amuses London… but hides the social fear embodied by Soubise.

In a rigid society where racial hierarchy is still the invisible foundation of the established order, Soubise is disturbing because he transcends his original condition. He is no longer the obedient slave. He is the one who speaks, laughs, parades, debates, dances, and teaches.

In 1777, Soubise’s rise ends abruptly. He leaves London for India. Officially to flee his excesses. Unofficially, a rumor grows: an accusation of sexual assault may have driven him into exile. Two days after his departure, the Duchess dies.

In Calcutta, he founds a riding and fencing school open… to women as well as men. Until his death, which occurred in 1798 following a fall from a horse, he tries to recreate a space of Black nobility, far from the West.

Julius Soubise left behind no books, no manifesto, no political heirs. But his image survives in engravings, memoirs, and abolitionist writings. Ignatius Sancho, a freed slave turned writer, addresses him in a letter urging him not to squander his chance.

What Soubise represents is rare and precious: the right to be more than a survivor. He was a partygoer, provocateur, dandy, athlete, artist… so many roles denied to his peers. His life is not a fairy tale. It is a crack in history: that of a Black man who, in a white man’s world, dared to play by their rules; and sometimes surpass them.

Notes et références

Miller, Monica L. Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, Duke University Press, 2009.

Carretta, Vincent. Unchained Voices: An Anthology of Black Authors in the English-Speaking World of the 18th Century, University Press of Kentucky, 2004.

Gerzina, Gretchen Holbrook. Black London: Life Before Emancipation, Rutgers University Press, 1995.

Rosenthal, Laura J. Infamous Commerce: Prostitution in Eighteenth-Century British Literature and Culture, Cornell University Press, 2006.

Angelo, Henry. The Reminiscences of Henry Angelo, Ayer Publishing, 1972.

Sancho, Ignatius. The Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African, Penguin Classics, edition annotated by Vincent Carretta, 1998.

Innes, Catherine Lynette. A History of Black and Asian Writing in Britain, 1700–2000, Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Ogborn, Miles. Spaces of Modernity: London’s Geographies 1680–1780, Guilford Press, 1998.

British Museum, A Mungo Macaroni, caricature by Matthew and Mary Darly (1772), accessed via BritishMuseum.org.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, entry “Soubise, Julius”, by Vincent Carretta (online edition, 2004).

Yale Center for British Art, The Duchess of Queensberry fencing with her protégé, 1773, William Austin, interactive.britishart.yale.edu.

National Archives UK, “Black Presence: Asian and Black History in Britain”, accessed January 17, 2007.

Summary

Julius Soubise: from chains to gilded salons

Notes and references