Frantz Fanon’s thought deeply influenced the strategy, discourse, and ideology of the Black Panther Party. Nofi explores this intellectual lineage between African anticolonial struggles and African American revolts, on the occasion of the release of Jean-Claude Barny’s film FANON.

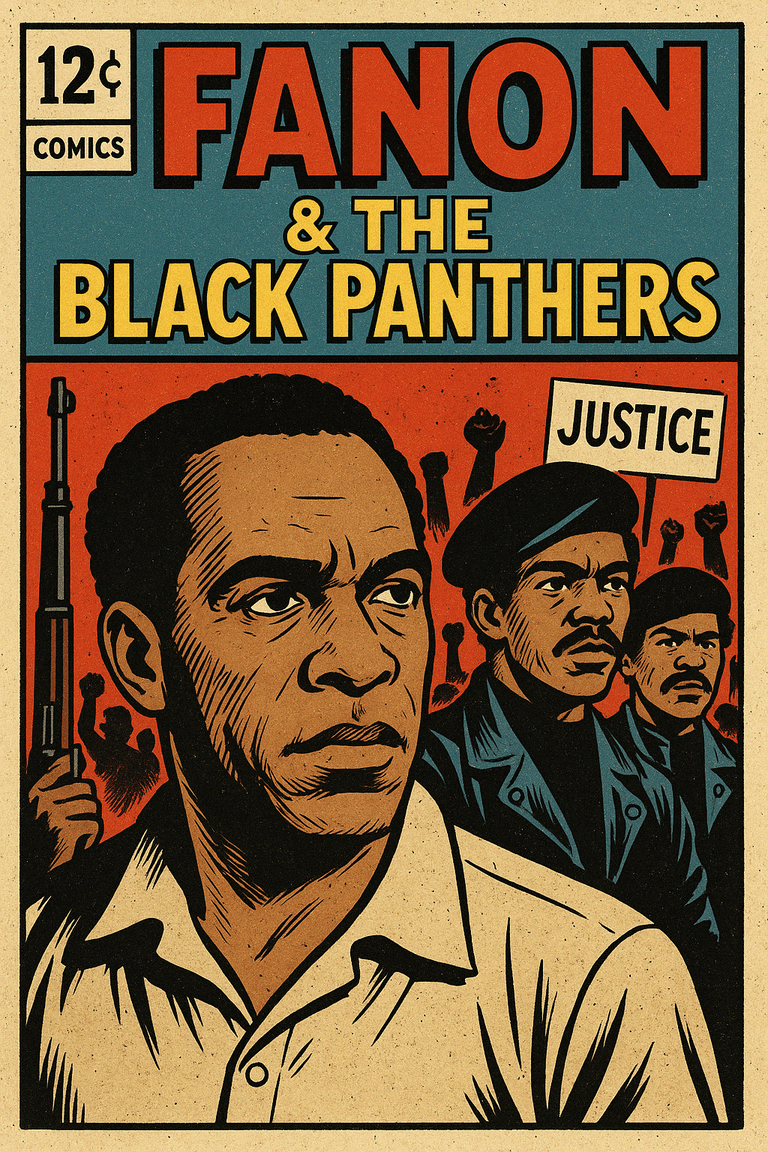

Books as weapons: When Fanon crossed the atlantic

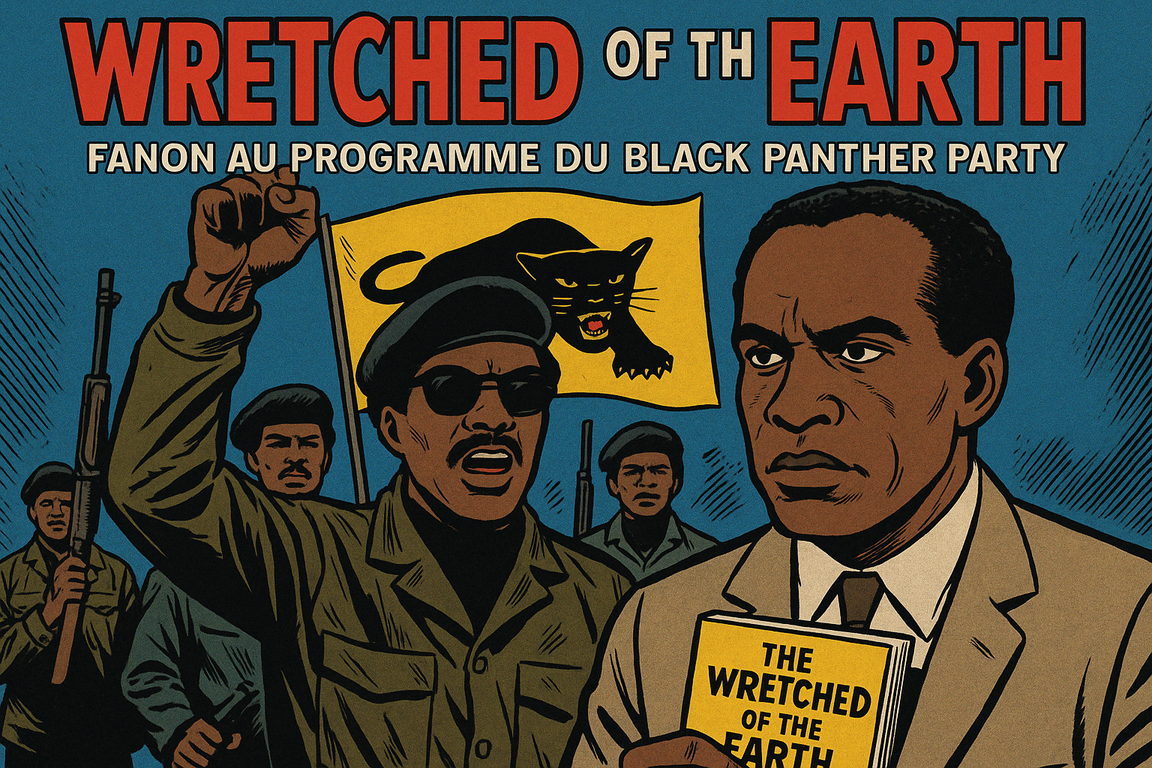

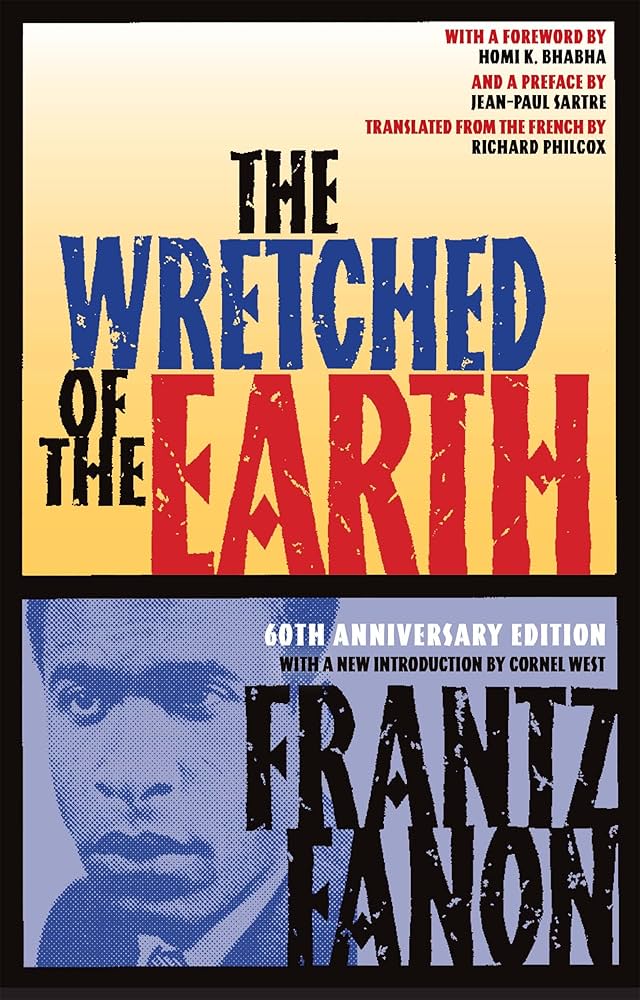

On October 15, 1966, in a small house in Oakland, two young Black activists eagerly flip through a worn-out book. Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton have just finished reading The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon, a searing work that, five years earlier, had galvanized Algerian anti-colonial fighters. “Decolonization is always a violent phenomenon,” Fanon declares right from the opening.

This sentence, like a theoretical thunderclap, resonates powerfully across the ocean. For Seale and Newton, about to found the Black Panther Party (BPP) in California, the parallel is a revelation: they too see themselves as a colonized people within their own country, the wretched of the earth fighting for their humanity.

In 2025, with the release of Jean-Claude Barny’s biopic FANON, it is striking to see how deeply Fanon’s thought shaped the Black Panthers’ approach—and how enduring this ideological connection remains.

Let’s dive into this transatlantic history, where the pen of the Martiniquan psychiatrist became a political weapon on America’s streets.

If, as we believe, the pages of History are the shifting sands of our identity, then revisiting the Fanonian legacy of the BPP sheds new light on our present struggles.

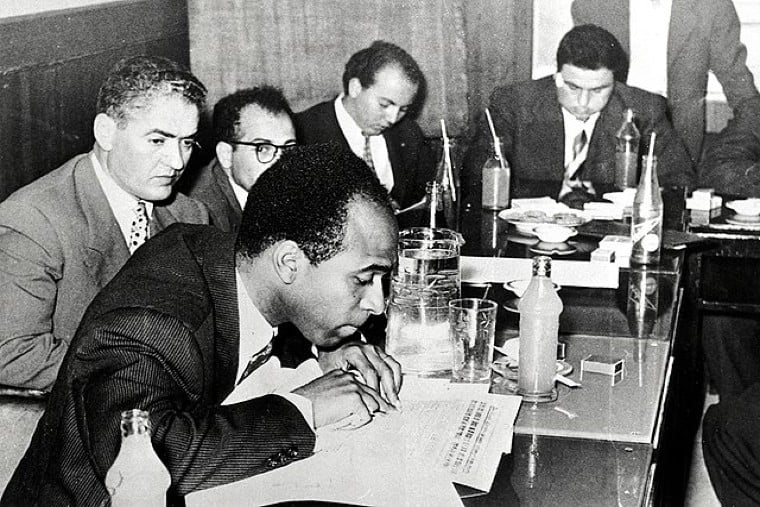

Born in 1925 in Martinique, Frantz Fanon became the voice of the revolting colonized during the 1950s. Having joined the National Liberation Front (FLN) during the Algerian War, he published Black Skin, White Masks (1952) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961), where he theorized colonial dehumanization and the necessity of liberating violence. As a trained psychiatrist, Fanon explored the psychological trauma of racism and proposed a “shock therapy”: only counter-violence could allow the colonized to break their mental chains.

His controversial idea—the notion of violence as catharsis and the rebirth of a “new man”—electrified Third World liberation movements. When Fanon died prematurely in 1961, his political testament crossed borders: the English translation of The Wretched of the Earth circulated clandestinely among African American activists.

In the United States, Black youth caught up in the Black Power movement recognized themselves in Fanon’s depiction of the wretched of the earth. In segregated ghettos, they knew they were relegated to what Fanon called the “zone of non-being,” described sharply in Black Skin, White Masks:

“Even at the risk of incurring the resentment of my brothers of color, I shall say that the Black man is not a man… There is a zone of non-being, an extraordinary region where the Black is an absence, where he learns to know himself through the eyes of the other.”

This direct critique of the cultural colonial mask resonated with young Black militants advocating Black is Beautiful and rejecting the demands of white respectability.

Fanon provided them with the vocabulary to name intimate wounds and invisible structures of oppression. His writing navigated between medical analysis of trauma and calls for uprising, giving Black anger intellectual legitimacy and an emancipatory horizon.

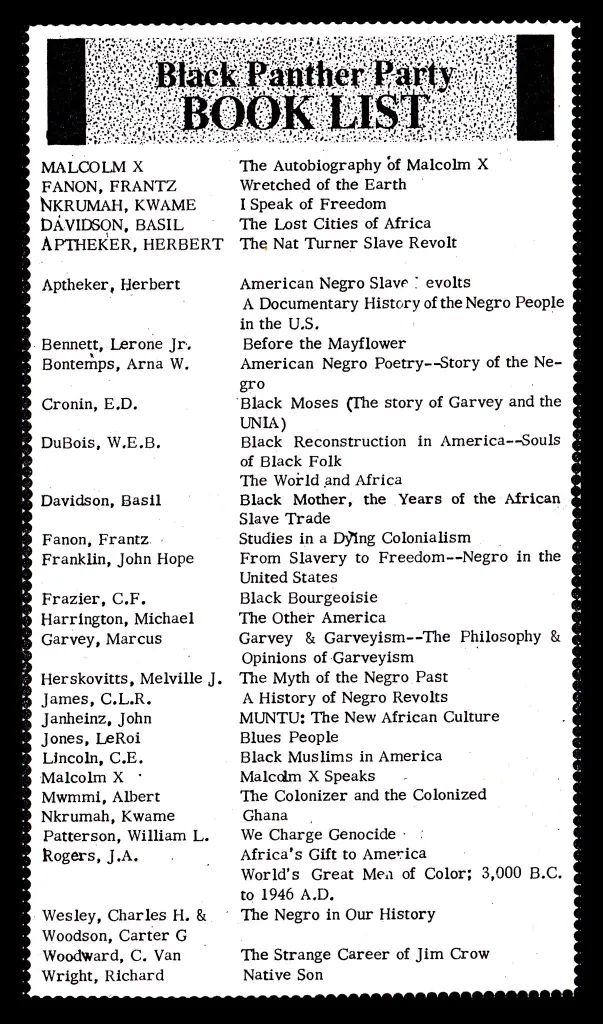

When Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in October 1966 in Oakland, they drew as much from the revolutionary thoughts of Marx, Malcolm X, and Mao Zedong as from Frantz Fanon. The Wretched of the Earth was required reading for every new party member. Former Black Panther Mumia Abu-Jamal recalled that every young Panther had to read Fanon’s work, no matter how complex the text translated from French.

The book became almost their political bible. Eldridge Cleaver (who would join the BPP in 1967 as Minister of Information) even called The Wretched of the Earth the “Black Bible” of the revolution.

Bobby Seale himself hurried to share his copy with Huey Newton when launching the movement. Newton, younger and more introverted than Seale, was nonetheless the primary theorist. An avid autodidact, Newton had already devoured Sartre and Camus; it was he who introduced Seale to existentialist philosophy and helped him “understand Frantz Fanon, this Afro-French psychiatrist who saw armed rebellion as a path to psychological liberation.”

Together, they forged the BPP’s ideology, connecting the local struggle of oppressed African Americans with the broader Third World revolutionary surge. Newton spoke of the “brothers on the street,” echoing Fanon’s wretched: marginalized populations (the unemployed, petty criminals, the excluded) were seen as the revolutionary vanguard.

Once again, the influence is clear: Fanon saw in the lumpenproletariat of the colonies—a class of thieves, prostitutes, and the destitute—a revolutionary force willing to risk everything for freedom. Newton adapted this idea to the American context, seeing the Black urban poor as the spearhead of radical change.

Beyond concepts, Fanon shaped the style and language of the Black Panthers. The fiery speeches of Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver borrowed the imagery of total confrontation found in The Wretched of the Earth. Newton even used the term “wretched of the earth” in his own writings to designate the oppressed exploited by American society.

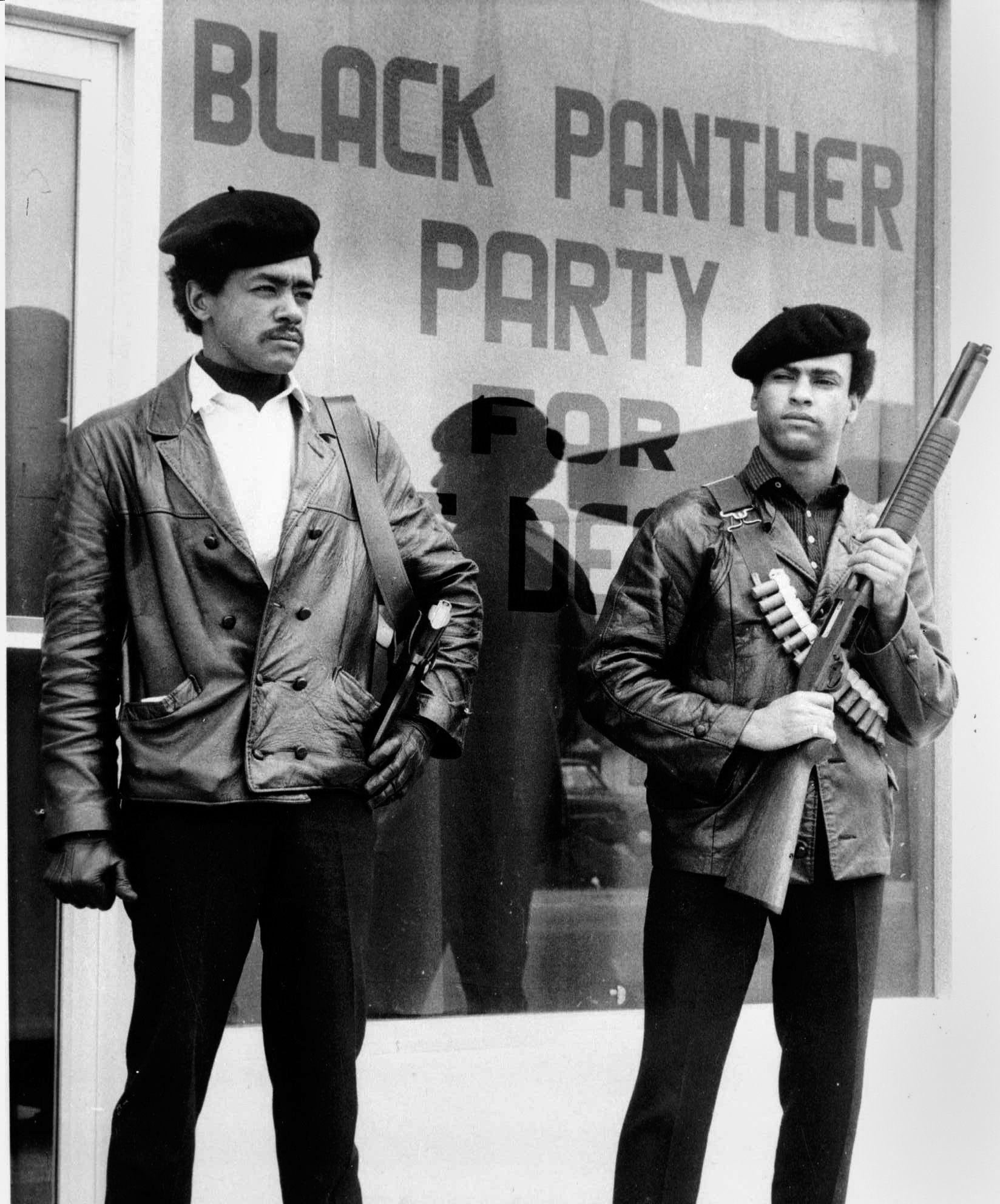

This was not just a literary homage: it crystallized the idea that the Black American ghetto was an internal colony, policed and oppressed much like Algerian villages under French occupation. “In the colonies, the agent of oppression is the policeman or the soldier,” Fanon wrote. The Panthers adopted this view, referring to police officers as “pigs” and organizing armed patrols to monitor police activity, directly challenging domestic colonial authority.

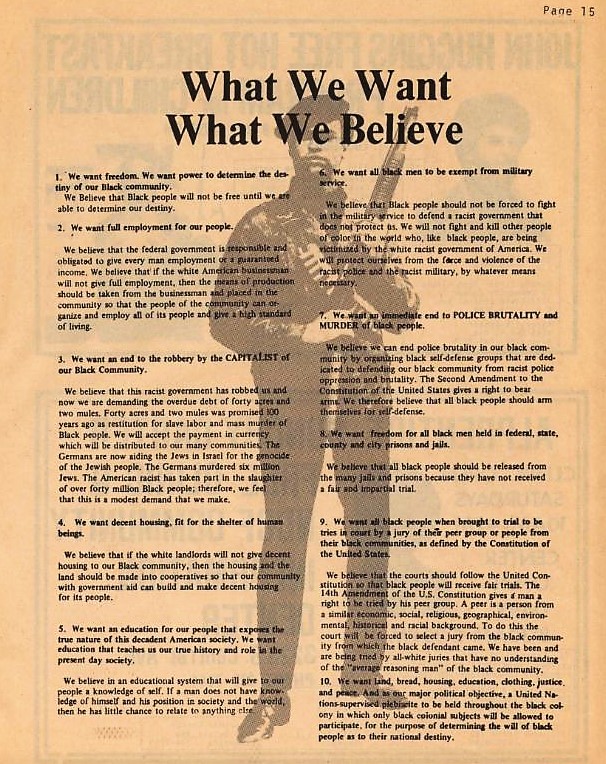

The BPP’s foundational manifesto also bore Fanon’s imprint. It demanded self-determination, historical education, decent housing, fair justice—in short, full dignity for Black people.

These demands showed that the Panthers’ struggle was part of a broader national liberation movement: “We want the power to determine the destiny of our Black community,” they proclaimed. Fanon could have co-signed these words, for he called every colonized people to seize their fate by force if necessary.

By reading Fanon, the Panthers found a global framework for their local rebellion—and, in return, the BPP gave concrete form on American soil to Fanon’s predictions about the expansion of the decolonial flame.

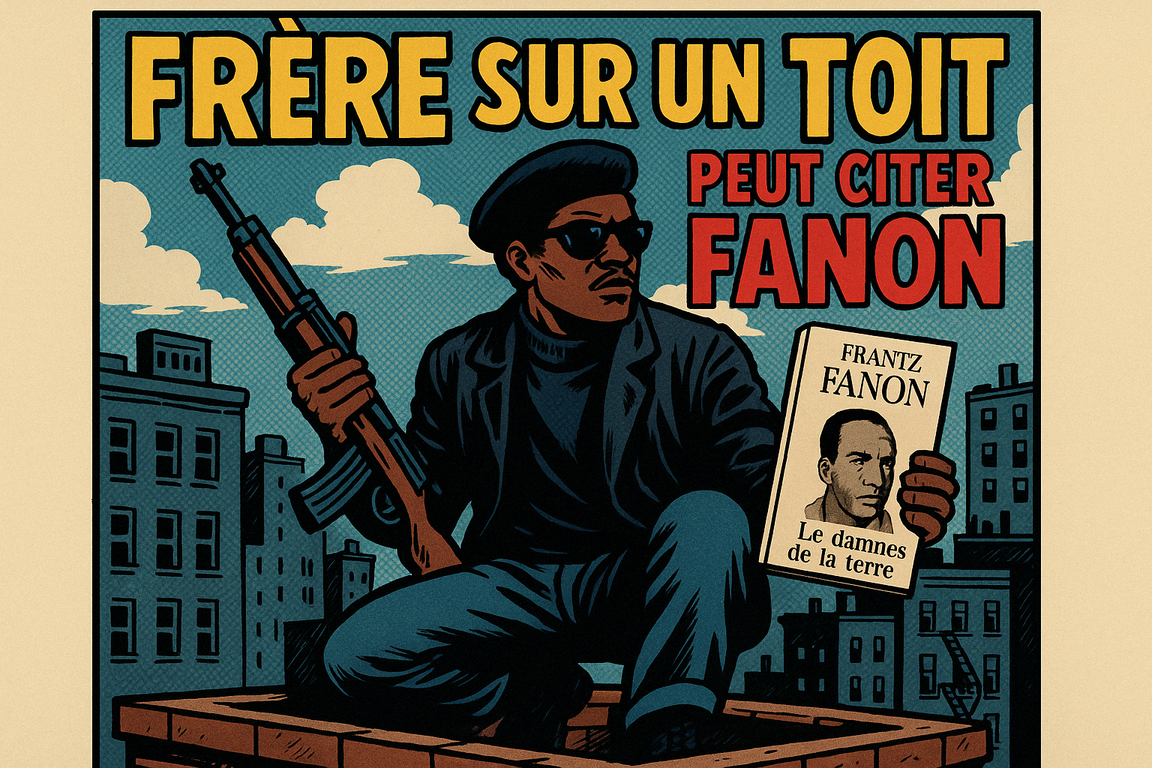

By 1967–68, the fusion of Fanonian theory and Panther practice reached its peak. “Every brother on a rooftop can quote Fanon,” noted radical Black editor Dan Watts. The image evoked armed sentinels posted on rooftops during urban uprisings (Watts, Detroit, etc.).

That a street fighter could recite Fanon illustrates how deeply Fanon’s ideas had permeated the political culture of Black youth. His writings offered both a manual for revolution — to unmask oppression and arm oneself to end it — and an antidote to resignation, restoring self-esteem through action.

Eldridge Cleaver, a sharp voice of the BPP, claimed that every word of Fanon could have been spoken by “any brother perched on a ghetto rooftop,” because Fanon’s prose spoke directly to the lived reality of Black Americans.

Cleaver himself openly drew on Fanon to theorize Black life in the United States. In his essays compiled in Soul on Ice (1968), he described the “white colonizer” imposing his canons of beauty and virtue, and the Black man torn between submission and revolt — extending Fanon’s analysis from Black Skin, White Masks.

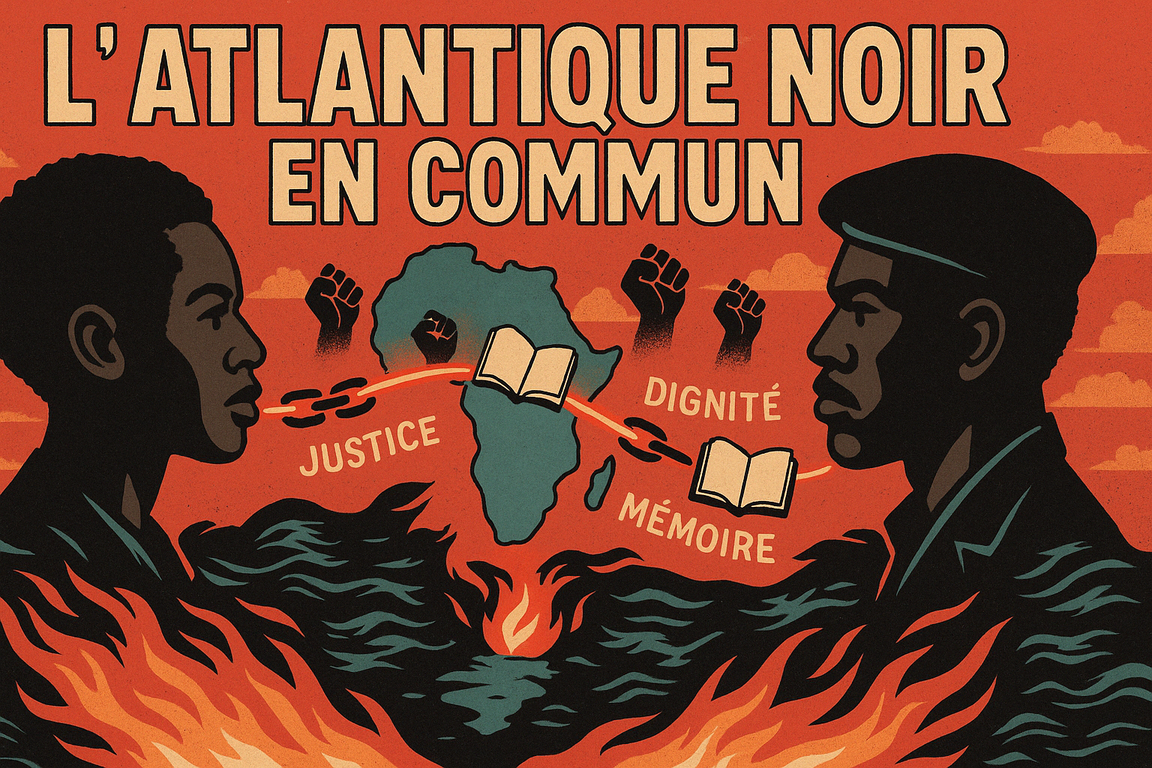

This intellectual connection soon transformed into concrete solidarity. In 1969, Cleaver exiled himself to Algeria — the revolutionary land that Fanon had helped liberate — to establish the Black Panther Party’s International Section. There, he was welcomed by Houari Boumédiène’s postcolonial government, which offered asylum to anti-imperialist struggles worldwide.

The circle was complete: on the very soil where Fanon wrote The Wretched of the Earth, a Black Panther leader continued the fight under new skies.

This symbolic convergence illustrated the continuum between African anticolonial struggles and African American struggles: same enemy (imperialist racism), same aspiration (freedom and dignity). Figures like Martin Luther King Jr. had praised Algerian independence, and Malcolm X had visited Algiers in 1964, declaring, “The Algerian Revolution is the model to follow.”

Fanon, who dreamed of an international alliance of the dispossessed, would undoubtedly have seen these transatlantic bridges as the concrete realization of his call for the convergence of struggles. The Black Panthers saw themselves as the American wing of a global front against colonialism, whether overt or insidious. Their newspaper, The Black Panther, covered not only the Black Panthers but also the war in Vietnam and African guerrilla movements, spreading within their community the idea that from Oakland to Hanoi, from Harlem to Algiers, the same historic battle was being fought.

Though the Black Panther Party’s history was tragically brief — repressed by the FBI and undermined by internal divisions in the early 1970s — its intellectual legacy endures. Fanon’s writings, reinterpreted through the experience of the Panthers, penetrated universities and contemporary activist movements. Entire fields — postcolonial theory, African American studies, decolonial thought — build upon the Fanon/Panther dialogue to analyze dynamics of race, power, and resistance.

As historian Adam Shatz explains, “Fanon’s thinking on the mental health of the oppressed and the liberating force of violence was adopted by the Black Panthers as early as the late 1960s,” and then spread far beyond. Over the decades, Fanon has become a subversive classic—one of those authors who are rediscovered during major social upheavals.

Fanon is cited to unravel the mechanisms of police brutality and systemic racism; he is also cited to restore hope and the courage to revolt. “Where the colonizer has left us with death, we must find life,” he seems to whisper still to new generations of activists.

The release of Jean-Claude Barny’s film FANON in 2025 thus comes at a moment of rediscovery. By bringing to the screen the life of the Martiniquan thinker (from his psychiatric service in Blida to his commitment to the Algerian cause), Barny helps make Fanon’s legacy accessible without diluting its radicalism.

The film highlights the journey of a man who believed in the transformative power of words and action, and whose ideas continue to positively haunt today’s struggles. It offers a new audience the opportunity to understand why the Black Panthers considered Fanon one of their spiritual prophets.

By weaving the threads from Algiers to Oakland, from Frantz Fanon to Huey Newton, we gain a better understanding of how anticolonial rage nourished African American revolt. It is not about idealizing the past or blindly advocating violence, but about recognizing the truth shared by Fanon and the Black Panthers: the emancipation of the oppressed requires a reclaiming of the self, a restoration of stolen dignity, even if it means shaking the established order.

“I am not a prisoner of History,” wrote Fanon. “In the world through which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself.” These words, the Panthers embodied in their own way, taking their destiny into their own hands, guns at the ready and books slung over their shoulders.

Even today, as racial inequalities persist and police violence rekindles anger, the Fanon–Black Panther connection offers a framework for thinking about action. It reminds us that local struggles are part of a global continuum, that each oppressed community echoes another, across borders and oceans.

Above all, it reminds us, like a haunting refrain, that the wretched of the earth have not spoken their last word. Their thirst for justice and freedom continues to inspire new generations, writing the next chapter of a History that it is up to us, together, to liberate.

Notes & Références

- Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (1961)

- Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (1952)

- Huey P. Newton, Revolutionary Suicide (1973)

- Bobby Seale, Seize the Time (1970)

- Eldridge Cleaver, Soul on Ice (1968)

- Dan Watts, editor of Liberator Magazine, 1968

- Mumia Abu-Jamal, We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black Panther Party (2004)

- Jean-Claude Barny, FANON (film, 2025)

- Adam Shatz, Fanon: The Revolutionary as Prophet, The Nation, 2001

- Black Panther Party Archives, Ten Point Program, 1966

Table of Contents

- Books as Weapons: When Fanon Crossed the Atlantic

- Notes & References