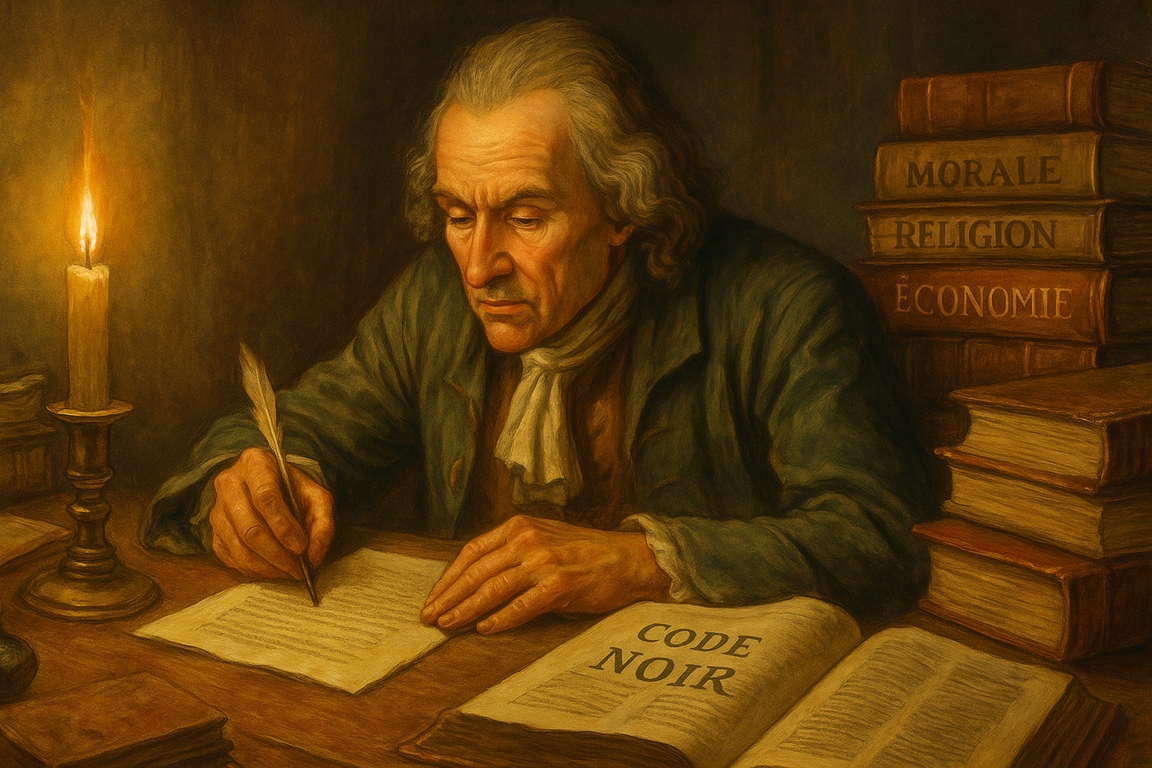

Written by Colbert and promulgated by Louis XIV in 1685, the Code Noir codified slavery in the French colonies. Behind its 60 articles lies a chilling hypocrisy: that of an empire claiming to civilize while commodifying Black lives. NOFI offers you a complete deep dive into this fundamental text to understand the legal roots of colonial oppression.

What is the Code Noir? A legislation in the service of slavery

They sought to codify the inhuman. To turn dehumanization into a decree.

The Code Noir is the moment when the French monarchical state dipped its pen into the blood of millions of African souls to write the legal architecture of colonial slavery.

It is not a law: it is an institutionalized slap. A declaration of war.

A cold, clinical, meticulous text – spelling out what Black bodies were supposedly worth: less than furniture, more than beasts, just enough to enrich a sugar-driven economy.

There are in fact two versions of this text.

The first, drafted under the initiative of Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683), Minister of the King and all-powerful Controller-General, was promulgated in March 1685 by Louis XIV, King of France from May 14, 1643 to September 1, 1715.

The second, a partial revision, was imposed by his successor Louis XV in 1724. On that occasion, some articles — 5, 7, 8, 18, and 25 — were simply removed.

What you are about to read here is the founding text: Colbert’s version from 1685.

The Code Noir, which claimed to curb the excesses of slave owners, only legitimized the intolerable.

It codified the slavery of Black people and the slave trade, sanctified by the Church and justified, at the time, by philosophers more concerned with order than justice.

Throughout its sixty articles oozes the hypocrisy of a legislator who, while feigning to recognize the humanity of the enslaved, actually locked them into a legal status of merchandise.

A movable good, subjected to market laws, integrated into a domain’s assets like a plow or a cart.

This document, which we publish here in its full annotated version, is not merely an archive.

It is evidence.

A gaping wound.

A heavy memory that we must confront.

Not to drown in pain, but to finally make a decolonial truth spring forth.

Because the past never truly passes until it has been read, understood, and exposed.

Here is the full text of the Code Noir of 1685, as written under Colbert’s authority and promulgated by Louis XIV: a fundamental document, to be read without detour.

Art. 1

We order that the Edict of the late king of glorious memory, our most honored lord and father, dated April 23, 1615, be enforced in our islands; to this effect, we command all our officers to expel from our said islands all Jews who have established their residence there, whom, as declared enemies of the Christian name, we command to leave within three months from the day of publication of these presents, under penalty of confiscation of body and goods.

Art. 2

All slaves who are in our islands shall be baptized and instructed in the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman religion. We enjoin upon the inhabitants who buy newly arrived negroes to notify the governors and intendant of said islands within a week at the latest, under penalty of arbitrary fine; who shall give the necessary orders for them to be instructed and baptized in due time.

Art. 3

We forbid all public exercise of any religion other than the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman. We wish that offenders be punished as rebels and disobedient to our commands. We forbid all assemblies for such purposes, which we declare conventicles, illicit and seditious, subject to the same punishment, applicable even against masters who permit or tolerate them among their slaves.

Art. 4

No overseers shall be appointed to direct the negroes who do not profess the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman religion, under penalty of confiscation of said negroes from the masters who appointed them, and arbitrary punishment against the overseers who accepted said office.

Art. 5

We forbid our subjects of the [Protestant] religion to cause any trouble or hindrance to our other subjects, even to their slaves, in the free exercise of the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman religion, under penalty of exemplary punishment.

Art. 6

We enjoin all our subjects, of whatever quality and condition they may be, to observe Sundays and feast days, as kept by our subjects of the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman religion. We forbid them to work or have their slaves work on said days, from midnight to the following midnight, whether in cultivating the land, manufacturing sugar, or any other work, under penalty of fine and arbitrary punishment against the masters and confiscation of both the sugars and the slaves caught by our officers at work.

Art. 7

We likewise forbid them to hold the negro market and any other merchandise market on said days, under the same penalty of confiscation of the merchandise found in the market at that time and an arbitrary fine against the merchants.

Art. 8

We declare that our subjects who are not of the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman religion are incapable of contracting any valid marriages in the future. We declare bastards the children born from such unions, which we wish to be held and regarded as true concubinage.

Art. 9

Free men who have had one or more children from concubinage with slaves, as well as the masters who tolerated it, shall each be condemned to a fine of 2000 pounds of sugar; and, if they are the masters of the slave with whom they had said children, we wish, besides the fine, that they be deprived of the slave and the children, who shall be assigned to the hospital, without ever being able to be freed. However, the present article shall not apply if the free man, who was not married to another person during his concubinage with his slave, marries the said slave in accordance with the forms observed by the Church, in which case she shall be freed and the children rendered free and legitimate.

Art. 10

The solemnities prescribed by the Ordinance of Blois and by the Declaration of 1639 for marriages shall be observed with regard to both free persons and slaves, without, however, requiring the consent of the slave’s father and mother, but only that of the master.

Art. 11

We expressly forbid priests from proceeding with slave marriages unless proof is shown of their masters’ consent. We also forbid masters from forcing their slaves to marry against their will.

Art. 12

Children born of marriages between slaves shall be slaves and shall belong to the masters of the slave women, not to those of their husbands, if the husband and wife have different masters.

Art. 13

We order that if a slave husband has married a free woman, the children, male or female, shall follow their mother’s condition and be free like her, notwithstanding the father’s servitude; and that if the father is free and the mother is a slave, the children shall also be slaves.

Art. 14

Masters shall be required to have their baptized slaves buried in consecrated ground, in cemeteries designated for this purpose. As for those who die without having received baptism, they shall be buried at night in a nearby field where they died.

Art. 15

We forbid slaves from carrying any offensive weapons or heavy sticks, under penalty of being whipped and having the weapons confiscated for the benefit of whoever finds them, except those sent hunting by their masters, bearing their master’s known permits or marks.

Art. 16

Likewise, we forbid slaves belonging to different masters from gathering by day or night under the pretext of weddings or otherwise, either at one of their masters’ homes or elsewhere, and even less on highways or in secluded places, under penalty of corporal punishment, which shall be no less than whipping and branding with a fleur-de-lys; and in cases of frequent recidivism and other aggravating circumstances, they may be punished with death, which we leave to the discretion of the judges. We enjoin all our subjects to attack the offenders, arrest them, and take them to prison, even if they are not officers and even if no decree has yet been issued against them.

Art. 17

Masters who are found to have permitted or tolerated such assemblies composed of slaves not belonging to them shall be condemned personally and privately to compensate any damage caused to their neighbors due to said assemblies and to a fine of 10 écus for the first time, and double in case of recurrence.

Art. 18

We forbid slaves from selling sugar cane for any cause or occasion whatsoever, even with their master’s permission, under penalty of whipping for the slave, a fine of 10 livres tournois for the master who permitted it, and the same fine for the buyer.

Art. 19

We also forbid them from putting up for sale at the market or carrying to private houses any kind of produce for sale, even fruits, vegetables, firewood, fodder, or their manufactured goods, without the express permission of their masters by a ticket or known mark; under penalty of reclamation of the goods thus sold, without restitution of price, in favor of the masters, and a fine of 6 livres tournois payable by the buyers to their profit.

Art. 20

We order that two persons be appointed by our officers at each market to inspect the goods and merchandise brought there by slaves, as well as the tickets and marks of their masters they must carry.

Art. 21

We allow all our subjects living in the islands to seize all goods found in the possession of slaves who do not have their master’s ticket or a known mark, to be immediately returned to their masters if their residence is near the place where the slaves were caught; otherwise, the goods shall immediately be sent to the hospital for safekeeping until the masters are notified.

Art. 22

Masters shall be required to supply each week, for the nourishment of their slaves aged ten years and older, two and a half pots, Paris measure, of manioc flour, or three cassavas each weighing at least two and a half pounds, or equivalent foodstuffs, with two pounds of salted beef, or three pounds of fish, or other equivalent food; and for children, from the time they are weaned until the age of ten, half the rations mentioned above.

Art. 23

We forbid masters from giving slaves cane brandy or guildive as a substitute for the subsistence mentioned in the previous article.

Art. 24

We likewise forbid masters from discharging themselves of the duty to feed and maintain their slaves by allowing them to work on certain days of the week for their own benefit.

Art. 25

Masters shall be required to provide each slave every year with two garments made of cloth or four ells of cloth, at the master’s discretion.

Art. 26

Slaves who are not fed, clothed, and maintained by their masters as we have ordered herein may inform our attorney general and submit their complaints to him, upon which, and even on his own initiative if the information comes from elsewhere, the masters shall be prosecuted at his request and without costs; we order this to be observed for crimes and barbarous and inhuman treatment by masters toward their slaves.

Art. 27

Slaves who are infirm due to old age, illness, or other causes, whether the illness is curable or not, shall be nourished and maintained by their masters, and if abandoned, said slaves shall be assigned to the hospital, and the masters shall be ordered to pay six sols per day for the nourishment and maintenance of each slave.

Art. 28

We declare that slaves can own nothing that does not belong to their masters; everything that comes to them through their industry, through gifts from others, or otherwise, by whatever title, shall be fully acquired by their masters, without the children of slaves, their fathers and mothers, their relatives, or others being able to claim any rights through succession, gifts, or death, all of which we declare null, as well as all promises and obligations they might have made, since they are incapable of managing or contracting for themselves.

Art. 29

Nevertheless, we wish that masters be responsible for what their slaves do by their command, as well as what they manage and negotiate in shops and in the particular line of business to which they are assigned; if the masters gave them no such orders or assignments, they shall only be liable to the extent of what they have profited, and if nothing profited them, the slaves’ peculium (personal savings) which their masters allowed them to have shall be liable after deducting what may be owed to the masters; unless the peculium consists wholly or partly of goods that slaves were permitted to trade separately, in which case the masters shall only share proportionally with other creditors.

Art. 30

Slaves cannot hold office or commission with any public function, nor be appointed as agents by anyone other than their masters for any business, nor act as arbitrators, experts, or witnesses, in civil or criminal matters; and if they are heard as witnesses, their testimony shall serve only as a memorandum to assist judges in gathering other evidence, without being grounds for presumption, conjecture, or admissible proof.

Art. 31

Slaves may neither be plaintiffs nor defendants in civil court matters, nor act as civil parties in criminal cases, except through their masters, who may act and defend on their behalf or pursue criminal reparations for offenses and abuses committed against their slaves.

Art. 32

Slaves may be criminally prosecuted without needing to involve their masters, except in cases of complicity; slaves accused shall be judged in the first instance by the ordinary judges and on appeal by the Sovereign Council, under the same instruction and formalities as free persons.

Art. 33

Any slave who strikes his master, mistress, the husband of his mistress, or their children, causing contusion, bloodshed, or hitting the face, shall be punished by death.

Art. 34

As for acts of violence committed by slaves against free persons, we wish them to be severely punished, even by death if appropriate.

Art. 35

Qualified thefts, including thefts of horses, mares, mules, oxen, or cows committed by slaves or freedmen, shall be punished by afflictive penalties, including death if the case requires.

Art. 36

Thefts of sheep, goats, pigs, poultry, sugar canes, peas, millet, manioc, or other vegetables committed by slaves shall be punished according to the gravity of the theft, by judges who may, if necessary, condemn them to be whipped by the public executioner and branded with a fleur-de-lys.

Art. 37

Masters shall be liable, in addition to the corporal punishment of their slaves, to repair any theft or damage caused by their slaves, unless they prefer to abandon the slave to the injured party, which they must opt for within three days of the judgment; otherwise, they lose the right to do so.

Art. 38

Any fugitive slave who has been on the run for one month from the day his master denounced him shall have his ears cut off and be branded with a fleur-de-lys on one shoulder; if he reoffends by another month of flight, he shall have his hamstring cut and be branded with a fleur-de-lys on the other shoulder; and the third time, he shall be punished with death.

Art. 39

Freedmen who harbor fugitive slaves shall be condemned personally to pay the masters a fine of 300 pounds of sugar per day of hiding; and other free persons who harbor them shall be fined 10 livres tournois per day.

Art. 40

Any slave condemned to death on the denunciation of his master (not being an accomplice in the crime) shall be appraised before execution by two principal inhabitants of the island, appointed by the judge; and the master shall be paid the appraised value. To satisfy this payment, an impost shall be levied by the intendant on each head of negroes paying duties, in proportion to the valuation, and collected by the royal domain farmer to avoid extra costs.

Art. 41

We forbid judges, our prosecutors, and clerks to take any fee in criminal cases against slaves, under penalty of extortion.

Art. 42

Masters may, when they believe their slaves deserve it, have them chained and beaten with whips or cords.

We forbid them from torturing them, mutilating them, under penalty of confiscation of the slaves and extraordinary proceedings against the masters.

Art. 43

We order our officers to criminally prosecute masters or overseers who kill a slave under their control or direction and to punish the murder according to the severity of the circumstances; and if there is cause for acquittal, we allow our officers to release both masters and overseers without them needing to obtain a letter of pardon from us.

Art. 44

We declare slaves to be movable property and, as such, part of the community property; they are not to be subject to mortgage, shall be divided equally among heirs without preference to the eldest, and shall not be subject to customary dower, feudal or lineage withdrawal, feudal rights, or formal decree requirements, nor subject to the deduction of four-fifths in testamentary dispositions.

Art. 45

We do not, however, intend to deprive our subjects of the ability to stipulate that said slaves be personal property for their side and line, just as is done for sums of money and other movable property.

Art. 46

In seizures of slaves, the forms prescribed by our ordinances and customs for movable property seizures shall be observed.

We want the proceeds distributed according to the order of seizures, or in case of bankruptcy, proportionally after privileged debts are paid, and generally that the condition of slaves be treated like that of other movable property, with the following exceptions.

Art. 47

The husband, wife, and their underage children, if they are all under the power of the same master, cannot be seized and sold separately.

We declare null any separate seizures or sales made, and we order that in such cases, those who attempt alienation be deprived of the slaves they tried to keep, who shall be awarded to the buyers, without requiring them to pay any price supplement.

Art. 48

Slaves currently working in sugar refineries, indigo mills, or plantations, aged fourteen to sixty, may not be seized for debts, except for debts arising from their purchase price or if the sugar refinery, indigo mill, or plantation where they work is itself seized; we forbid, under penalty of nullity, any seizure of such plantations without including the slaves working there.

Art. 49

The judicial lessee of sugar refineries, indigo mills, or plantations seized along with the slaves shall be required to pay the full price of his lease, without being allowed to count among the fruits he collects the children born to slaves during the lease.

Art. 50

We wish, notwithstanding any contrary agreements, which we declare null, that the said children belong to the seized property if the creditors are otherwise satisfied, or to the adjudicatee if a decree occurs.

To that end, the last notice before the decree must mention the children born to the slaves since the real seizure.

The same notice shall mention any slaves who died since the seizure.

Art. 51

To avoid costs and delays in proceedings, the entire price from the adjudication of lands and slaves shall be distributed among the creditors according to the order of their privileges and mortgages, without distinguishing what is from the sale of lands and what is from the sale of slaves.

Art. 52

Nevertheless, feudal and seigniorial rights shall only be paid in proportion to the price of the lands.

Art. 53

Lords by lineage and feudal lords cannot redeem the seized lands unless they also redeem the slaves sold with them, nor can the adjudicatee retain the slaves without the lands.

Art. 54

We order noble and bourgeois guardians, usufructuaries, lessees, and others managing lands attached to slaves, to govern said slaves as good fathers of families, without being required, after their administration ends, to reimburse the value of those who died or diminished by illness, old age, or otherwise without fault of the guardian, and without retaining as fruits the children born during their administration, who must be preserved and returned to the rightful owners.

Art. 55

Masters aged twenty years or older may emancipate their slaves by any act, whether inter vivos or mortis causa, without being required to give reasons, nor needing advice from relatives even if they are under twenty-five years old.

Art. 56

Slaves made universal legatees by their masters, or appointed executors of their wills or guardians of their children, shall be held and regarded as freed.

Art. 57

We declare that emancipation granted in our islands shall be equivalent to birth there and that freed slaves shall not require letters of naturalization to enjoy the rights of natural-born subjects of our kingdom, lands, and dominions, even if born abroad.

Art. 58

We order freedmen to show particular respect toward their former masters, their widows, and their children, such that any insult made to them shall be punished more severely than if made to another person; yet we declare them free and released from all other charges, services, and rights that their former masters might claim over them as patrons.

Art. 59

We grant freedmen the same rights, privileges, and immunities enjoyed by persons born free; we wish that the merit of acquired liberty produces for them the same effects as natural liberty brings to our other subjects.

Art. 60

We declare that confiscations and fines not otherwise designated by these presents belong to us, to be collected by those appointed to receive our rights and revenues; nevertheless, we order that one-third of said confiscations and fines be assigned to the hospital established on the island where they were adjudicated.

Notes and References

- Code noir: Royal ordinance of March 1685 on the condition of slaves in the French colonies, known as the “Code noir”, promulgated by Louis XIV. It contains 60 articles. Text available via Gallica: https://gallica.bnf.fr

- Louis Sala-Molins, Le Code noir ou le calvaire de Canaan, Paris, PUF, 1987 (4th ed.). The author qualifies this text as “the most monstrous legislative document of modern times.”

- Jean-François Niort, Le Code noir : idées reçues sur un texte symbolique, Paris, Le Cavalier Bleu, 2015. The historian defends a contextualized approach, rejecting a purely moral reading of the text.

- On the drafting of the Code noir: Vernon Valentine Palmer, “Essay on the Origins and Authors of the Code noir”, Revue internationale de droit comparé, vol. 50, no. 1, 1998, p. 111-140.

- Robert Chesnais, Le Code noir, Paris, L’esprit frappeur, 1998. Introduction and critical notes on the 1685 version.

- The Code noir was also promulgated under Louis XV, in a modified version in 1724 for Louisiana.

- Articles 5, 7, 8, 18, and 25 of the 1685 text were not retained in the 1724 version.

- For a comparative analysis of the two versions: Niort J.-F. and Richard J., “The Royal Edict of March 1685 called the Code noir: selected, compared and commented versions”, Droits, no. 50, 2010, p. 143-161.

- The religious dimension (baptism, Catholic instruction, prohibition of non-Christian worships) is discussed in: Jean-Frédéric Schaub, “1683: A French 1492?”, in Histoire mondiale de la France, dir. P. Boucheron, Seuil, 2017.

- For an understanding of how the Enlightenment received the Code noir: Diderot, Histoire des deux Indes, digital edition on Wikisource.

Summary

- What is the Code Noir? A legislation in the service of slavery

- Notes and references