In the Caribbean, an 8% price reduction on 6,000 products in 2025 should be seen as a victory. But for populations where food remains up to 40% more expensive than in mainland France, and where structural inequality is rooted in a colonial past, the mood is one of revolt. Nofi explores the deep-rooted causes of the high cost of living and the social movements, like those led by the RPPRAC, that demand radical transformation.

The illusion of superficial victories

In the Caribbean, the 2025 announcement of an 8% reduction on nearly 6,000 products was met with a mix of relief and skepticism. After months of mass mobilizations, notably led by the Airprac collective, the government presented this move as a response to social demands. But behind this seemingly promising announcement, the daily reality of the inhabitants remains largely unchanged.

A partial victory, but at what cost?

While the price reductions were significant for some essential goods, they did little to offset the persistent high cost of living across the Caribbean territories. Families continue to pay food prices that are on average 40% higher than in mainland France, with even starker differences for certain common products. For example, a pack of bottled water sold for 10 euros in the Caribbean costs only 2 euros in mainland France. These stark disparities don’t just affect food: hygiene products, construction materials, and even services like internet access are also impacted.

While the 8% reduction appears to symbolize a major concession, it actually represents only a fraction of the original commitment to reduce prices by 20%, promised during the agreement signed in October 2024. Worse, the savings on some products are quickly offset by increases on others, a common strategy used by major retailers to protect their profit margins.

A crushing socio-economic context

This situation is all the more unbearable given that Caribbean incomes are significantly lower than those in mainland France. The median monthly income in these territories is on average 300 euros lower, which amplifies the impact of high prices on household budgets. For many families, this gap translates into increased precariousness, particularly in accessing essential goods like potable water, which remains problematic for hundreds of thousands of Caribbean residents.

With such economic imbalance, local consumers are forced to make impossible choices: prioritize food over other basic needs, or turn to lower-quality products, often cheaply imported but harmful to health. Precarity hits young people especially hard, with unemployment rates approaching 60% for those under 25, creating a vicious cycle of social exclusion and economic dependency.

Why do solutions keep failing?

In the face of this reality, the solutions proposed by the French state, such as the partial abolition of the octroi de mer (a local import tax) or VAT exemptions, seem largely insufficient. These superficial measures fail to address the deep-rooted causes of the high cost of living, which are entrenched in a colonial economy designed to keep the Caribbean dependent on mainland France. While the octroi de mer has been lightened, it continues to inflate the costs of imported goods, and the lack of local economic diversification prevents the development of viable alternatives.

Furthermore, the distribution of the gains from these reductions remains opaque, and local economic actors—often dominated by family monopolies—are not required to pass these savings on to consumers. In the end, it is the Caribbean people themselves who pay for these reductions through decreased resources for local governments that rely on the octroi de mer to finance their infrastructure.

A victory for whom?

Popular mobilizations, while effective in drawing attention to these systemic issues, face increased state repression. The arrest of the RPPRAC collective’s spokesperson, Rodrigue Petittot, and several activists illustrates the difficulty of achieving significant progress without facing the wrath of the authorities. Meanwhile, large distribution companies continue to accumulate profits, protected by an economic system that favors monopolies and local elites.

Thus, the central question remains: can we truly speak of victory when the solutions implemented merely scratch the surface of structural issues? This observation paves the way for a deeper analysis of the root causes of the high cost of living and the colonial dynamics that continue to weigh heavily on the Caribbean.

Part 1: The legacy of the Octroi de Mer – A colonial relic

The octroi de mer, a tax little known to the general public in mainland France, is a cornerstone of the Caribbean economy. This fiscal system, inherited from the colonial era, is often presented as a tool to support the local economy. But behind this facade lies a much darker reality: the octroi de mer perpetuates an unequal economic structure, hinders the development of overseas territories, and places a disproportionate burden on the Caribbean people themselves.

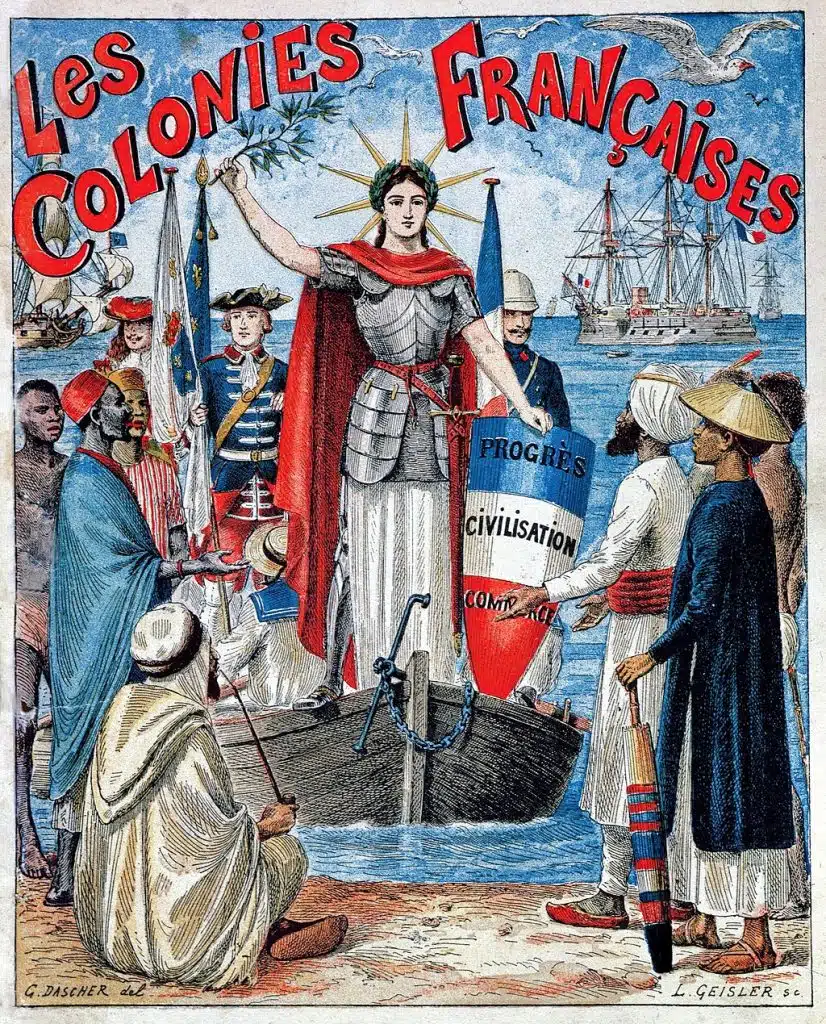

Historical origins: A tax of colonial exploitation

Created in 1670, the octroi de mer had a clear objective: to finance colonial infrastructure and enrich slave-owning plantation owners. It was a tax levied on all products imported into the colonies, ostensibly to protect local production, primarily agricultural and focused on plantation economies. This fiscal system was designed in a context of economic domination, where the primary goal was to maximize the profits of the colonial elites while keeping the colonies dependent on the metropole.

At the time, imported goods were heavily taxed—except for those intended to maintain the slave system. For example, weapons and equipment needed to suppress enslaved people were exempt from this tax, an exception that highlights how the octroi de mer was structured to reinforce economic and social oppression.

Current function: Between local funding and contradictions

Today, although slavery has been abolished for centuries, the octroi de mer still exists but with a different function. The tax still applies to imported goods in the Caribbean, with rates ranging from 0% to 50%. The revenue generated now serves to fund local governments, particularly the salaries of municipal workers and some public infrastructure.

On paper, this system seems beneficial: it helps compensate for the weak local tax resources due to the low level of industrialization and fragile economic structure of the Caribbean. In practice, however, the octroi de mer heavily burdens consumers. The tax, combined with already high import and logistics costs, further inflates the prices of basic goods.

A regressive tax system: Caribbean people fund their own price reductions

One of the most glaring paradoxes of the octroi de mer lies in its role during the 2025 price reduction negotiations. To achieve an average 8% reduction on 6,000 products, the state partially abolished this tax on certain consumer goods. While this measure eased household bills, it also deprived local governments of a crucial source of revenue. Moreover, no significant compensation was provided by the French state to offset this shortfall.

In other words, the Caribbean people are effectively paying for their own price reductions. This phenomenon reflects a broader reality: while the octroi de mer funds public services, it acts as a regressive tax. The poorest households, which spend a larger portion of their income on taxed products, are disproportionately affected compared to wealthier households. Consequently, the octroi de mer exacerbates the deep social and economic inequalities in these territories.

Critical analysis: A barrier to local development

Beyond its impact on consumers, the octroi de mer also poses structural problems for the Caribbean economy. By artificially protecting certain local productions from external competition, this tax discourages investments in strategic sectors and stifles innovation. Local entrepreneurs, faced with high costs and limited markets, struggle to develop activities that can compete with imports.

Moreover, the octroi de mer reinforces the Caribbean’s economic dependence on mainland France. A large portion of the products consumed in the overseas territories come from France or Europe, rather than being imported from neighboring countries in the Caribbean or Latin America, which could offer cheaper alternatives. This choice, inherited from the colonial pact, keeps the Caribbean in a position of economic and logistical subordination.

Testimonies from local economists: A necessary reform

Several Caribbean economists and researchers have long denounced the perverse effects of the octroi de mer. Jean-Pierre Sainton, a Guadeloupean historian, emphasizes that this tax “perpetuates a colonial logic of dependence and the capture of local resources.” Similarly, Olivier Sudrie, an economist specializing in overseas economies, argues that “the octroi de mer is a barrier to the industrial development of the Caribbean, as it protects inefficient monopolies while penalizing consumers and entrepreneurs.”

For these experts, the solution lies in a deep reform of the overseas fiscal system. This could include a gradual reduction of the octroi de mer, offset by increased state support for local governments, as well as investments in strategic sectors like agriculture and renewable energy. These measures would reduce the Caribbean’s dependence on the metropole and promote a transition toward a more diversified and sustainable economy.

A tax to rethink, not abolish

While the octroi de mer is often criticized, its complete abolition would not be without risks. Local governments, which heavily rely on this tax to fund their budgets, would be severely affected without a solid compensation plan. Furthermore, a sudden elimination could further destabilize certain local industries that benefit from the protection offered by the octroi de mer.

Thus, the question is not whether the octroi de mer should disappear, but how to transform it into a tool that genuinely benefits the Caribbean. By redirecting this tax to support strategic sectors and easing its burden on essential goods, it would be possible to reconcile economic development with social justice.

In conclusion, while the octroi de mer is a relic of a colonial past, it remains a central element in the debate over the high cost of living in the Caribbean. Its reform, far from being a simple technical adjustment, represents a major political challenge for the future of these territories. It raises a fundamental question: should the Caribbean continue to bear the burden of a system inherited from colonization, or can it finally break free to build a more equitable and resilient economy?

Part 2: A stratified society – Racial and economic inequality

The economy of the French Caribbean cannot be understood without exploring its historical roots, deeply embedded in its colonial legacy. Beyond income disparities, the social fabric of the Caribbean is marked by structural racial and economic inequalities that perpetuate a system of social stratification, where economic elites continue to thrive at the expense of the majority. This stratification, a product of the region’s history of slavery and colonialism, shapes not only economic opportunities but also social tensions and the aspirations of local populations.

Colonial legacy: A béké elite still in power

One of the most striking features of Caribbean society is the disproportionate economic power held by the békés, descendants of slave-owning colonists. Although they represent only about 1% of the population, these families own nearly 40% of the local economy, including agricultural land, major businesses, and distribution chains. Their economic dominance dates back to the era of slavery, where they amassed considerable wealth through the exploitation of enslaved people on sugar plantations.

After the abolition of slavery in 1848, the békés not only retained their lands but also received financial compensation from the French state for the loss of their “human property,” further consolidating their economic power. Today, this minority continues to benefit from intergenerational wealth, while the majority of Caribbean people—descendants of slaves—remain excluded from wealth and opportunities.

Caribbean economist Jean-Pierre Sainton explains:

“THE BÉKÉS SYMBOLIZE BOTH THE COLONIAL PAST AND PERSISTENT ECONOMIC INEQUALITIES. THEIR ECONOMIC DOMINANCE CREATES A DEEP DIVIDE BETWEEN A PRIVILEGED ELITE AND A LARGELY MARGINALIZED POPULATION.”

Social inequalities: Returnees, mainland french, and locals

Beyond the békés, other dynamics contribute to reinforcing inequalities in Caribbean societies. Among them, the divide between returnees, mainland French (métropolitains), and locals (sédentaires) plays a key role.

- Returnees: These are Caribbean people who left their island, often to pursue studies or economic opportunities in mainland France, and later returned. Although they share cultural roots with locals, their experience in mainland France often allows them to access better-paying jobs and positions of power. They also benefit from networks and social capital that give them a competitive edge in the local job market.

- Mainland French (Métropolitains): Civil servants and executives from mainland France disproportionately occupy leadership and prestigious positions in public and private institutions. Thanks to public sector salaries increased by 40% (a high-cost-of-living allowance), they enjoy a significantly higher purchasing power than locals, further exacerbating economic inequalities.

- Locals (Sédentaires): These are Caribbean people who have never left their island. They constitute the majority of the population but are often relegated to the lowest-paid or most precarious jobs. Their limited access to higher education and economic opportunities contributes to a vicious cycle of poverty.

These disparities are further exacerbated by the weakness of local educational and economic infrastructures. For instance, the Caribbean lacks a well-developed university network, forcing many young people to emigrate to pursue higher education. As a result, opportunities remain concentrated in the hands of those who can afford to leave, while the others face a saturated local job market.

Youth unemployment: A generational crisis

Among the most alarming indicators of this social stratification is youth unemployment, which has reached critical levels. In Guadeloupe and Martinique, over 60% of young people under 25 are unemployed. This figure is one of the highest in the European Union and reflects the failure of public policies to offer future prospects to an entire generation.

The lack of qualified jobs, coupled with an economy dominated by monopolies and a public administration controlled by mainland officials, deprives young Caribbean people of viable economic opportunities. As a result, many young people turn to alternative solutions, such as emigration or, in some cases, informal or illegal activities.

Malcolm, a 23-year-old graduate from Martinique, shares:

“I DID EVERYTHING THEY ASKED: I STUDIED, I GOT MY DEGREE, BUT THERE’S NOTHING HERE FOR ME. I APPLIED TO DOZENS OF JOBS, BUT THE GOOD POSITIONS ALWAYS GO TO PEOPLE FROM MAINLAND FRANCE OR THOSE WITH CONNECTIONS.”

Youth unemployment also has significant social repercussions, fueling intergenerational tensions and a sense of abandonment. In some working-class neighborhoods, despair leads to risky behaviors, such as violence or dropping out of school.

Testimonies: “A sacrificed youth suffocated by an unjust system”

Social stratification isn’t just a matter of statistics. It manifests in the stories of those who live it daily. Sophie, a teacher in Martinique, observes:

“EVERY DAY, I SEE BRIGHT, TALENTED YOUNG PEOPLE, BUT THEY’RE SUFFOCATED BY A SYSTEM THAT GIVES THEM NO CHANCE. HOW CAN THEY DREAM OF A BETTER FUTURE WHEN THEY SEE THAT EVERYTHING IS BLOCKED FOR THEM?”

This feeling of suffocation is especially palpable in public institutions, where decisions are often made by mainland officials who are unfamiliar with local realities. This lack of representation fuels growing distrust towards authorities, perceived as disconnected from the concerns of Caribbean populations.

A Stratification to Deconstruct

The colonial legacy and contemporary dynamics have built a deeply unequal society in the Caribbean, where race, social class, and geographical origins largely determine economic opportunities. To break this vicious cycle, it is imperative to invest in public policies aimed at:

- Strengthening local education: Develop universities and training centers to limit the exodus of young people.

- Promoting equal opportunities: Facilitate access for Caribbean people to leadership positions in both the public and private sectors.

- Reforming economic inequalities: Reduce wage gaps and provide economic prospects for marginalized populations.

Despite the obstacles, young Caribbean people continue to dream of a future where their potential can finally flourish. But without a profound overhaul of the system, this dream risks remaining out of reach for many.

Part 3: The economic monopoly – GBH and Pwofitasyon

In the French overseas territories, the issue of the high cost of living is not limited to taxes and logistical dependence on mainland France. A key factor lies in the economic structure of the Caribbean, dominated by a handful of family groups that hold monopolies over production and distribution chains. Among them, the Groupe Bernard Hayot (GBH) epitomizes the dynamics of pwofitasyon, a Creole term referring to the economic and social exploitation of local populations for the profit of a privileged elite.

The opacity of commercial margins: A game of blurred numbers

Officially, profit margins in Caribbean retail range from 14% to 22%, rates comparable to those in mainland France. However, several investigations and testimonies reveal a very different reality, marked by opaque commercial practices and the accumulation of margins at every stage of the supply chain.

A 2009 government report, already alarming at the time, highlighted “significant anomalies” in the margins reported by major groups. Figures were sometimes unverifiable, costs unjustified, and billing practices opaque. More recently, a senior executive at GBH, speaking anonymously to Libération, revealed that profit margins on certain products were three to four times higher than in mainland France. According to him, this situation is made possible by the near-monopoly exercised by GBH and other major companies in the Caribbean market.

Cumulative margins become even more problematic when considering the Caribbean’s economic structure: at each stage—importation, distribution, retail—profits are captured by the same groups, which control the entire supply chain. For example, GBH, through its subsidiaries, is both importer, distributor, and retailer, allowing it to maximize profits while making financial practices difficult to scrutinize.

Portrait of Bernard Hayot and GBH: An empire built on colonial heritage

Groupe Bernard Hayot (GBH) is today an indispensable player in the Caribbean economy. Founded in 1960 by Bernard Hayot, a descendant of a béké family—descendants of European colonists settled in the Caribbean—GBH quickly established itself as one of the most powerful conglomerates in the region. Nicknamed “the emperor of retail” by L’Express, Hayot now controls a sprawling economic empire spanning retail (Carrefour, Euromarché), the automotive industry (Toyota, BMW), and even construction.

This wealth, however, rests on a foundation of slavery and colonialism. Like other béké families, the Hayots amassed their initial capital through the plantation economy, which was based on slavery. In 1849, after the abolition of slavery, the Hayot family, like all slave-owning families, received substantial compensation from the French state for the loss of their “human property.” This capital was then reinvested in various economic sectors, allowing GBH to expand and prosper.

Today, GBH controls 60% of the retail market in the Caribbean, a monopoly that allows it to exert considerable influence over prices. For many residents, Bernard Hayot symbolizes pwofitasyon, an economic and social exploitation inherited from colonialism.

Consumer testimonies: “We pay for the luxury of a few”

For Caribbean consumers, the omnipresence of GBH and other major groups translates into exorbitant prices for basic necessities. Yogurts sold 100% more expensive than in mainland France, water packs reaching 10 euros compared to 2 euros in the Hexagon. These prices, unbearable for a population whose median income is 300 euros lower than in mainland France, fuel a sense of revolt.

Marie-Laure, a single mother in Guadeloupe, shares:

“EVERY MONTH, I HAVE TO CHOOSE BETWEEN PAYING MY BILLS AND BUYING FOOD. THE PRICES IN SUPERMARKETS ARE OUTRAGEOUS. WHILE WE TIGHTEN OUR BELTS, SOME BUILD VILLAS AND DRIVE LUXURY CARS. WE PAY FOR THE LUXURY OF A FEW.”

This sense of injustice is reinforced by the cultural and economic dominance of the békés, who, though a minority (1% of the population), hold 40% of the local economy. This concentration of wealth creates an ever-widening gap between the economic elites and the rest of the population.

Investigating cumulative margin practices

Cumulative margin practices in distribution are a systemic issue in the Caribbean. GBH and other major groups exploit a vertical economic structure where every stage—from importation to retail—generates profits that stack on top of each other. For example:

- Importation: Products are purchased at competitive prices on the international market, but shipping costs are inflated to justify higher prices.

- Distribution: GBH, as the main distributor, adds a significant margin, often hard to justify.

- Retail: Supermarkets apply a final layer of margins, making products even less accessible.

A study commissioned in 2021 by a local NGO revealed that nearly 30% of the final price of products consisted of cumulative margins, a figure far higher than the average observed in mainland France. This situation is particularly problematic for essential goods, where the poorest families spend a disproportionate share of their income.

Reactions and prospects

In response to this situation, several voices are calling out these practices and demanding stricter regulation of monopolies. The Collectif contre la pwofitasyon (LKP) in Guadeloupe, for instance, advocates for greater transparency in commercial margins and the implementation of price caps on essential goods. However, these demands face resistance from the state and powerful economic lobbies.

At the same time, local economists are calling for a diversification of supply chains, encouraging imports from neighboring countries like Jamaica or the Dominican Republic instead of limiting trade to the metropole. This shift would require strong political will and investments in local infrastructure, but it could reduce costs for consumers while stimulating the regional economy.

A monopoly to break, an economy to rethink

The monopoly exercised by GBH and other major groups in the Caribbean is a symptom of the economic and social inequalities inherited from colonialism. Behind the opaque figures and questionable commercial practices lies a harsh reality: Caribbean people pay a high price to maintain the profits of a privileged elite. Pwofitasyon, far from being just a slogan, is a daily reality for thousands of families struggling to make ends meet.

Breaking this monopoly and deeply reforming local economic structures won’t be easy tasks. But they are necessary steps to build a fairer economy where the wealth generated in the Caribbean benefits those who live there first. Until these changes are implemented, the specter of pwofitasyon will continue to haunt the islands, a reminder that true equality remains a distant goal.

Part 4: Dependence on mainland France – An intact colonial structure

The French Caribbean is often described as “overseas territories” attached to France, but behind this administrative term lies a structural dependence on the mainland, inherited from a colonial logic that has never been fundamentally challenged. This dependence is reflected in economic, agricultural, and commercial choices that deprive the Caribbean of its autonomy, reinforcing its vulnerability to economic and social crises.

Colonial pact and autarky: Why does the Caribbean import 80% of its food from Europe?

To understand the Caribbean’s economic dependence, we must go back to the colonial pact imposed by France in the 17th century. According to this policy, colonies were required to export their raw materials exclusively to the mainland and import their manufactured goods from France. This system guaranteed a captive market for French products while preventing the colonies from developing their own industries or trading freely with other regions.

Today, although this colonial pact has officially disappeared, its effects persist in a modernized form. The Caribbean imports about 80% of its food, much of which comes from Europe, despite the geographical proximity of producers in Latin America and the Caribbean. This commercial autarky imposed by France maintains an expensive and inefficient economic dependence.

Products imported from Europe are often subject to high transportation costs and taxes that inflate their prices. For example, it is common to find tomatoes or grapes from Spain and Italy in Caribbean supermarkets, even though these islands could produce their own fruits and vegetables suited to their tropical climate.

Impact of colonial markups on essential products

Colonial markups, a term referring to the additional costs associated with the Caribbean’s economic dependence on the mainland, have direct repercussions on the purchasing power of local populations. For instance, a pack of water often costs four times more in the Caribbean than in mainland France. Similarly, essential products like yogurt or cereals are sometimes priced 100% higher than those in France.

These markups are not solely the result of taxes or commercial margins. They are also linked to vertically integrated logistics, where each step—from production in Europe to transportation to the Caribbean—generates additional costs. The companies that dominate this logistics chain, often based in mainland France, accumulate profits at each stage, contributing to the maintenance of high prices.

According to a 2024 government report, the French Caribbean territories are among the regions with the highest cost of living within the European Union. Yet the proposed solutions, such as VAT exemptions, do not address the root causes of this dependence but merely serve to temporarily ease social tensions.

The agricultural model based on banana export: The “bananization” of the Caribbean

Caribbean agriculture is another area where dependence on the mainland is glaringly evident. For decades, the Caribbean has been locked into an agricultural model based on banana exports to Europe, to the detriment of local production intended to feed the population. This situation, which eco-philosopher Malcolm Ferdinand calls the “bananization” of the Caribbean, reflects an economy inherited from the plantation system of the colonial era.

The monoculture of bananas, encouraged by European subsidies, monopolizes much of the agricultural land. These subsidies allow Caribbean banana producers to remain competitive in the European market, but they do not benefit the local economy. As a result, the Caribbean must import a large portion of its food, including staple products like rice, milk, and meat.

This food dependence makes the Caribbean particularly vulnerable to global price fluctuations and supply chain disruptions. Meanwhile, fertile lands that could be used to produce food for local populations are monopolized by large export-oriented plantations.

Farmers’ testimonies: “We could feed our people, but the land Is seized”

Local farmers regularly express their frustration with this system, which prevents them from developing diversified and sustainable agriculture. André, a small farmer in Guadeloupe, explains:

“THE LAND IS IN THE HANDS OF A FEW LARGE FAMILIES OR COMPANIES. WE, SMALL PRODUCERS, CAN’T AFFORD ACCESS TO THIS LAND OR THE FINANCIAL SUPPORT NEEDED TO GROW ANYTHING OTHER THAN BANANAS. YET WE COULD PRODUCE ENOUGH FRUITS, VEGETABLES, AND CEREALS TO FEED EVERYONE HERE.”

This situation is further exacerbated by the use of pesticides like chlordecone, which have contaminated part of the agricultural land, making cultivation difficult and hazardous to health.

“THIS AGRICULTURAL MODEL IS NOT ONLY INEFFICIENT BUT ALSO TOXIC,” says Marie-Claire, a farmer in Martinique.

“WE ARE STUCK IN AN EXPORT LOGIC THAT ONLY BENEFITS LARGE COMPANIES, WHILE OUR FAMILIES STRUGGLE TO FEED THEMSELVES.”

A Colonial dependence embedded in institutions

The Caribbean’s economic dependence on the mainland is a structural problem deeply rooted in institutions. It reflects an economic strategy where France maintains control over its former colonies by keeping them economically and logistically dependent. This model is not merely a relic of the past but an active policy that perpetuates economic inequalities and hinders the autonomous development of the Caribbean.

Breaking this vicious cycle would require reorienting the Caribbean economy toward regional integration with neighboring countries in the Caribbean and Latin America. Such an approach would demand not only massive investments in local infrastructure but also the political will to challenge the interests of large corporations and the dependency relationships with the mainland.

A dependence to deconstruct

Dependence on the mainland is more than just an economic issue: it is a form of modernized colonial control that deprives the Caribbean of its autonomy and stifles its development. As long as this system persists, superficial solutions such as temporary price reductions or VAT exemptions will only scratch the surface of the problems. For Caribbean populations, true economic liberation requires a radical rethinking of the colonial structures still in place.

Part 5: The state’s repressive response to social movements

Social movements advocating for a more affordable life in the Caribbean are not new, but they have taken on unprecedented scale in recent years. Faced with a frustrated youth, glaring inequalities, and an economy still marked by the colonial legacy, thousands of citizens have mobilized to demand structural changes. However, instead of responding to these demands with meaningful reforms, the French state has opted for a repressive strategy, seeking to criminalize movement leaders and suppress any political dissent.

The arrest of Rodrigue Petittot (“le R”) and the criminalization of activists

The most emblematic case of this repression is that of Rodrigue Petittot, known as “le R,” spokesperson for the RPPRAC (Rassemblement pour la Protection des Peuples et des Ressources Afro-Caribéennes). This collective, at the forefront of mobilizations against the high cost of living, organized massive demonstrations throughout 2024, denouncing not only exorbitant prices but also the structural economic injustice suffered by the Caribbean.

On October 26, 2024, ten days after signing an agreement to reduce prices by 20% on 6,000 products, Rodrigue Petittot was arrested for trespassing at the prefectural residence. This widely publicized arrest was perceived by many activists as an attempt to silence the movement. Petittot is currently in pre-trial detention awaiting his trial scheduled for January 21, 2025.

The government did not stop there. In addition to Petittot, nearly 3,000 activists from the collective were targeted by repressive measures, including the movement’s treasurer and the spokesperson’s bodyguard. These mass arrests created a climate of fear among activists, while sending a clear message: challenging the state’s economic policies can have serious consequences.

Testimonies from collective members: “We are criminalized for defending our dignity”

For RPPRAC members, the repression they face is a deliberate attempt to divert attention from the real issues. When asked about the arrests, one activist from the collective stated:

“WE ARE NOT CRIMINALS. WE ARE SIMPLY DEMANDING WHAT IS RIGHTFULLY OURS: A DIGNIFIED LIFE, FAIR PRICES, AND AN END TO ECONOMIC INJUSTICE. BUT EVERY TIME WE RAISE OUR VOICES, THE STATE SEEKS TO SILENCE US BY FORCE.”

Other testimonies highlight the extent of the repression. A young activist arrested during a demonstration explains:

“THEY WANT TO PAINT US AS TROUBLEMAKERS, BUT THE TRUTH IS, WE REPRESENT A YOUTH THAT IS TIRED OF BEING SACRIFICED. IF WE DON’T FIGHT FOR OUR RIGHTS, WHO WILL?”

These testimonies reveal how state repression fuels frustration and anger among activists. Rather than discouraging mobilizations, it could instead intensify them as the Airprac collective gains popular support. les intensifier à mesure que le collectif Airprac gagne en soutien populaire.

A state strategy to marginalize political demands

Repression is not limited to arrests. It fits into a broader strategy aimed at marginalizing the Caribbean’s political demands and reducing them to mere public disturbances. This strategy relies on several levers:

- Media stigmatization of activists: Members of RPPRAC are often portrayed in the media as troublemakers or individuals seeking to destabilize the established order. This narrative discredits their legitimate demands and isolates them from the rest of the population.

- Criminalization of collective actions: Peaceful demonstrations are frequently repressed under the pretext that they threaten public security. Mass arrests and vandalism accusations are used to justify this repression, even when activists’ actions are non-violent.

- Lack of dialogue: The French government has rarely taken the time to engage in constructive dialogue with movement leaders. Agreements obtained, such as the 2024 price reduction, are often superficial compromises that do not address the activists’ deeper demands.

This strategy only deepens the rift between the state and Caribbean populations, reinforcing the idea that the Caribbean is viewed as a territory to be managed rather than as a partner to be heard.

Repression with colonial roots

The use of force to respond to social movements in overseas territories is nothing new. It is part of a long history of authoritarian crisis management in French colonies. In the 20th century, anti-colonial movements in the Caribbean, Algeria, and Madagascar were brutally repressed, often under the pretext of protecting “public order.”

Today, although the Caribbean is administratively part of France, this repressive approach echoes colonial practices. By criminalizing leaders and minimizing demands, the state reproduces patterns of domination and marginalization that perpetuate inequalities and fuel resentment.

Mobilization as a response to repression

In the face of this repression, the RPPRAC collective and other local organizations continue to rally crowds. Demonstrations organized in the streets of Caribbean cities and sometimes in Paris testify to the determination of activists to be heard.

The state’s response raises a fundamental question: how can an authentic dialogue be built when repression becomes the default response? For many activists, repression only strengthens their conviction that radical changes are necessary to break the cycle of economic and social injustice.

An uncertain future

As Rodrigue Petittot’s trial approaches, the future of the RPPRAC movement remains uncertain. Repression may push some activists toward radicalization, while others might seek more institutional means of dialogue. What is clear, however, is that the demands for a fairer and more equitable life in the Caribbean will not disappear. If the state persists in its repressive strategy, it could face even broader and more determined opposition in the years to come.

Part 6: What solutions for economic emancipation?

The recurring crises related to the high cost of living in the Caribbean highlight a harsh reality: superficial solutions, such as VAT exemptions or promises of price reductions, are not enough. The economic emancipation of the Caribbean requires a comprehensive and radical approach that addresses not only the symptoms but, more importantly, the root causes of economic precariousness and structural dependence on mainland France. This section explores possible solutions, considering economic, social, and geopolitical perspectives.

Short-term perspectives: Price controls and VAT exemptions

In the short term, price controls on essential goods remain an unavoidable measure to alleviate the economic pressure on Caribbean households. The government’s 2024 promise to reduce prices by 20% on 6,000 products falls within this logic. However, as evidenced by the actual reduction of only 8% in 2025, these efforts are often insufficient and poorly implemented.

VAT exemptions, already applied in Mayotte and considered for other Overseas Territories, are another potential measure. These initiatives aim to reduce the final cost of products but have their limitations:

- Limited impact on inequality: These exemptions benefit everyone, including wealthier households, without directly targeting the most vulnerable populations.

- Lack of transparency: As with the “octroi de mer” (sea duty), the effectiveness of these measures depends on the willingness of major retailers to pass on these reductions to consumers.

- Local budget deficit: These exemptions deprive local authorities of essential resources, increasing their financial dependence on the state.

A local economist’s testimony highlights this point:

“VAT EXEMPTIONS ARE JUST A BAND-AID ON A GAPPING WOUND. WITHOUT STRICT CONTROL OF MARGINS AND AN OVERHAUL OF ECONOMIC CIRCUITS, THESE MEASURES ONLY PROLONG THE AGONY.”

Developing food and energy autonomy: An imperative for the future

One of the keys to breaking the cycle of economic dependence is developing food and energy autonomy. Currently, the Caribbean imports more than 80% of its food from Europe, even though its climate and agricultural potential would allow for the local production of most essential goods.

Reorienting agriculture: Moving beyond “bananization”

As researcher Malcolm Ferdinand points out in his concept of “bananization,” the Caribbean’s agricultural economy is still largely structured around the monoculture of bananas for export to the mainland. This historical focus prevents the development of local subsistence crops.

A testimony from a Martinican farmer illustrates this:

“WE HAVE THE LAND, THE KNOW-HOW, AND YET WE IMPORT TOMATOES FROM SPAIN AND APPLES FROM FRANCE. WHY NOT USE OUR RESOURCES TO FEED OUR OWN POPULATION?”

Energy sovereignty: Harnessing renewable resources

The Caribbean benefits from abundant sunlight and access to natural resources such as wind and geothermal energy. Yet, the energy transition remains in its infancy. Investing in renewable energy infrastructure would not only reduce dependence on fossil fuel imports but also create local jobs.

Testimonials from solidarity economy experts: “Emancipation requires diversification and sovereignty”

Many experts in the solidarity economy advocate for a more inclusive and sustainable approach, centered on economic diversification and investment in local projects.

An analysis from a local economy expert explains:

“TO BREAK FREE FROM DEPENDENCE, COMMUNITIES MUST BE EMPOWERED TO BUILD THEIR OWN ECONOMY. THIS MEANS AGRICULTURAL COOPERATIVES, LOCAL MARKETS, AND MICRO-ENTERPRISES SUPPORTED BY APPROPRIATE FINANCING.”

Inspiring example: In Guadeloupe, some community associations are experimenting with permaculture systems that, in addition to reducing dependence on imports, reintroduce ancestral farming practices respectful of the environment.

Geopolitical reflection: The impact of the United States and regional integration as a lever

The Caribbean cannot envision its economic future without considering its immediate geopolitical environment. In a region heavily influenced by the United States, regional integration could offer opportunities to diversify economic partnerships and reduce dependence on France.

The role of the united states in the region

Historically, the United States has exerted considerable influence in the Caribbean, often to the detriment of the region’s autonomy. Economic sanctions imposed on countries like Cuba and Venezuela complicate regional trade, limiting opportunities for the French Caribbean to engage with its immediate neighbors.

Regional integration as a solution

Economic integration with other Caribbean nations could allow the French Caribbean to develop more equitable and geographically closer trade partnerships. Organizations like CARICOM (Caribbean Community) provide frameworks to promote regional cooperation, but their potential remains underutilized.

A Caribbean economist’s testimony emphasizes this:

“THE FRENCH CARIBBEAN MUST STOP LOOKING EXCLUSIVELY TO MAINLAND FRANCE. BY ESTABLISHING TRADE LINKS WITH NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES, THEY COULD BENEFIT FROM MORE COMPETITIVE PRICES AND ENRICHING CULTURAL EXCHANGES.”

Building a collective future

To one day break the cycle of dependence and precariousness, the Caribbean must embark on a bold path: that of economic, food, and energy autonomy. But these changes cannot happen without massive state support and a genuine political will to address the root causes of inequality.

The ball is now in the court of policymakers, but also of local populations, who must continue to mobilize to ensure their voices are heard. The economic emancipation of the Caribbean will not be easy, but it is essential to ensure a fairer and more equitable future.

Between resistance and determination: What path for the future?

The future of the French Caribbean is at a decisive crossroads between two fundamental choices: real equality or economic independence. This dilemma, rooted in a colonial past that remains all too present, reflects the complexity of the challenges these territories face. To escape the trap of high living costs, structural inequalities, and economic dependence, more than superficial measures or temporary reforms will be required. A profound transformation—economic, social, and political—is necessary.

The choices ahead: Real equality or economic independence?

Real equality, within a republican framework, would mean aligning living conditions and opportunities between the Caribbean and mainland France. This would involve:

- Rigorous price controls to ensure essential goods are accessible to all.

- Fair tax reform, particularly on taxes like the octroi de mer and VAT, to ease the economic burden on the most modest households.

- Massive investments in education, vocational training, and local infrastructure to break the vicious cycle of unemployment and inequality.

However, history shows that these promises of real equality have often been delayed or sabotaged by institutional mechanisms that favor the mainland and large economic groups at the expense of local populations.

On the other hand, economic independence represents a bolder but also more uncertain option. It would require:

- Developing food sovereignty to reduce dependence on costly imports.

- Diversifying trade partners by relying on regional integration with other Caribbean nations.

- Revaluing agricultural land and local practices, breaking away from the monoculture logic aimed at export.

This path, however, requires financial resources and technical skills that cannot emerge without breaking away from the patterns inherited from colonial economic structures.

Tribute to popular mobilizations and the courage of Caribbean residents

Faced with these challenges, the popular mobilizations in the Caribbean illustrate admirable resilience and determination. The fight against pwofitasyon (economic exploitation), the denunciation of monopolies and social inequalities, and the demand for a dignified life for all reflect a collective courage that does not waver.

The Airprac movement, for example, embodies this spirit of resistance. Despite repression, arrests, and intimidation, activists continue to fight for economic and social justice. Their commitment, far from isolated, is part of a long tradition of anti-colonial struggles and aspirations for a more equitable society.

A Guadeloupean activist shares:

“WE KNOW THE ROAD IS LONG, BUT WE HAVE NO CHOICE. IF WE DON’T STAND UP TO DEFEND OUR RIGHTS, WHO WILL?”

These mobilizations also remind us that viable solutions cannot be imposed from above. They must be co-constructed with local communities, listening to their needs and valuing their knowledge.

Final reflection: Can we hope for transformation without breaking from colonial models?

The current issues facing the French Caribbean are not historical accidents but direct consequences of an economic and social system designed to maintain colonial domination. As long as this model persists, the solutions provided will be insufficient.

Can we truly reform a system built on injustice and exploitation? This question remains central. Resistance to structural reforms, whether from the state or economic elites, shows that the status quo benefits some at the expense of the majority.

To hope for lasting transformation, we will likely need to accept a break from the models inherited from the colonial past. This means rethinking how the Caribbean interacts with the mainland and redefining its place in the Caribbean region and the world.

A Caribbean economist’s quote sums it up:

“THE ECONOMIC EMANCIPATION OF THE CARIBBEAN CANNOT HAPPEN AS LONG AS WE CONTINUE FOLLOWING A PATH LAID OUT FOR US AND NOT BY US.”

A future to write collectively

This struggle for dignity and economic justice is a generational challenge, but it also carries a promise of hope. The French Caribbean has always drawn from its history of resistance to forge new paths. Its future will depend on its ability to transform this resilience into collective action, demand profound reforms, and, above all, never abandon its dreams of emancipation.

The time is no longer for waiting for miraculous solutions from elsewhere. Change will come from a collective awakening, a willingness to break free from the invisible chains of the past, and a firm commitment to building a society based on justice, equality, and solidarity.

Notes and references

- Analysis of the Octroi de Mer: INSEE and CEROM report, 2022

- Investigation into GBH Practices: Libération, 2024

- Testimonials on Pwofitasyon: Video archives of the LKP movement, 2009

- Studies on the Bananization of the Caribbean: Malcolm Ferdinand, A Decolonial Ecology

- Articles on Social Mobilizations: Le Monde, 2024