The transatlantic slave trade remains one of history’s darkest chapters. Between 1525 and 1866, millions of Africans were captured and forcibly transported under inhumane conditions to the New World, destined for a life of slavery and suffering. Explore the horrific reality of voyages aboard slave ships—floating vessels of terror where thousands perished before even reaching the land their oppressors promised.

A journey into horror

Beginning in the 16th century, a grim trade network was established between Europe, Africa, and the New World: the transatlantic slave trade. From 1525 to 1866, over 12 million African men, women, and children were torn from their homelands, captured like livestock, and shipped to the Americas, where they would serve as enslaved labor in tobacco, sugar, and cotton plantations. This unimaginably brutal journey stands as one of the darkest chapters in human history. For these captives, crossing the Atlantic, known as “the Middle Passage,” was not just a journey; it was a descent into hell, marking the beginning of a life of horror and servitude.

In this account, Nofi delves into the terrifying reality of these crossings, a world where human beings were reduced to mere commodities, bound for suffering from the moment they boarded.

Captivity and embarkation

The tragedy’s first stage began on the West African coast. The Guinea Coast, Benin, and Congo were central points in this hellish machine. Captives were seized during violent raids or sometimes sold by local chiefs, entangled in a system of trade deeply rooted in betrayal and violence. Chained together, captives were led to coastal forts where they waited, sometimes for weeks or even months, crammed into filthy enclosures, starved and brutalized, until the slave ships arrived.

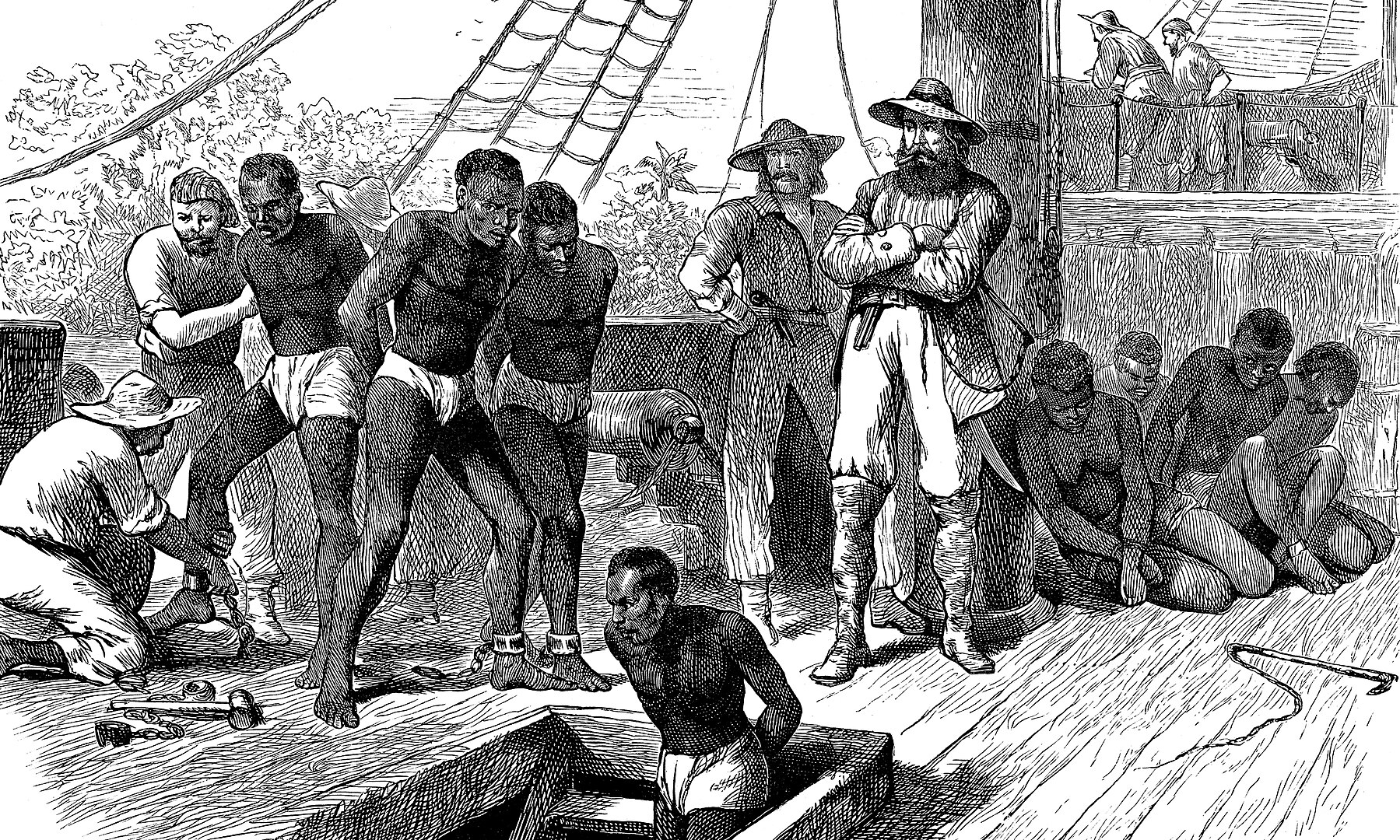

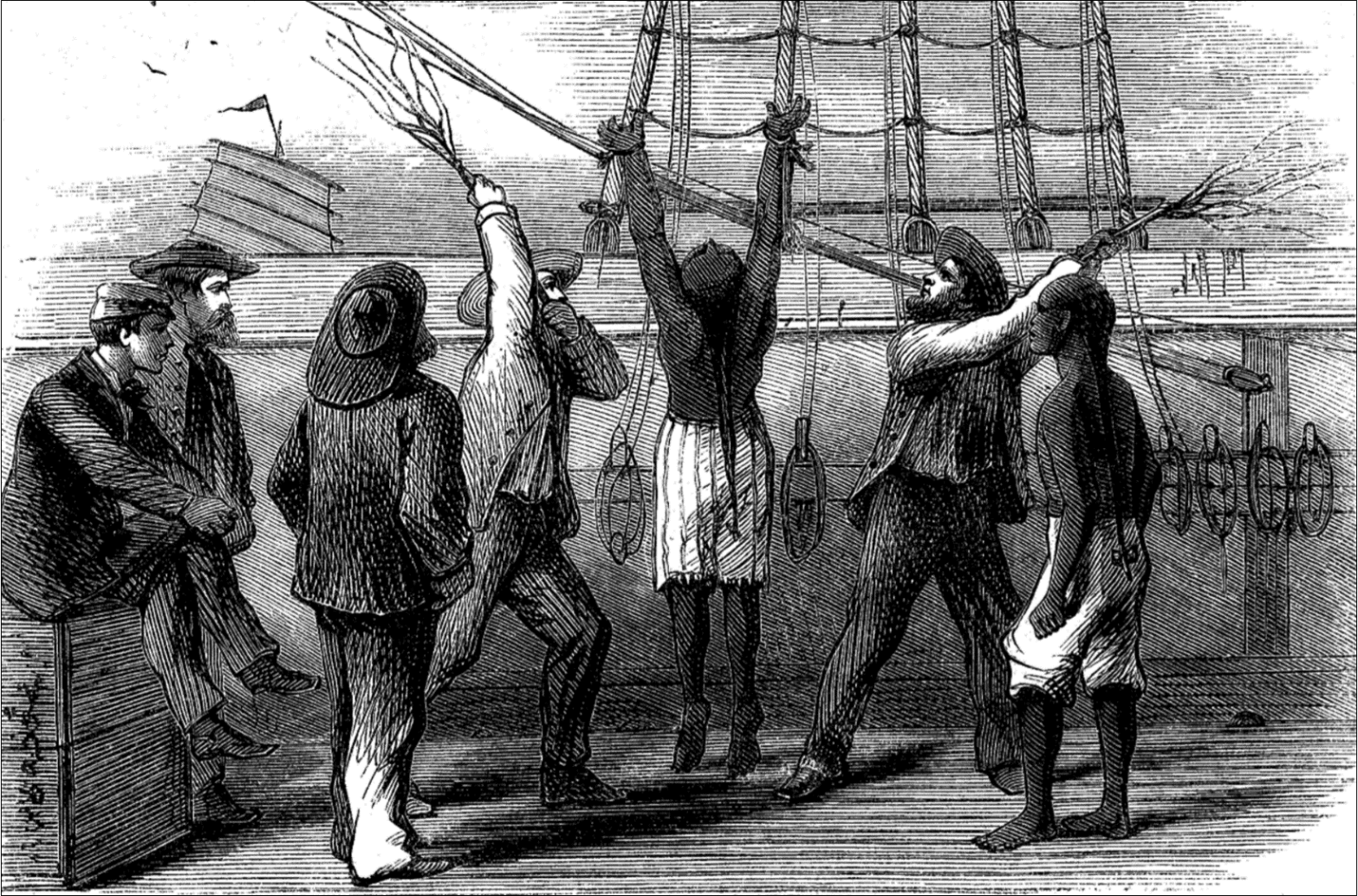

When it was finally time to board, captives underwent a series of humiliating and dehumanizing treatments. Their heads were shaved, they were stripped, and inspected as if they were livestock. Slave traders arranged them methodically in the ship’s hold, maximizing profit by utilizing every inch of available space. These “Guineans,” named after the Guinea Coast from which they departed, were packed in so tightly that the hold became a nightmarish confinement.

Hell in the holds

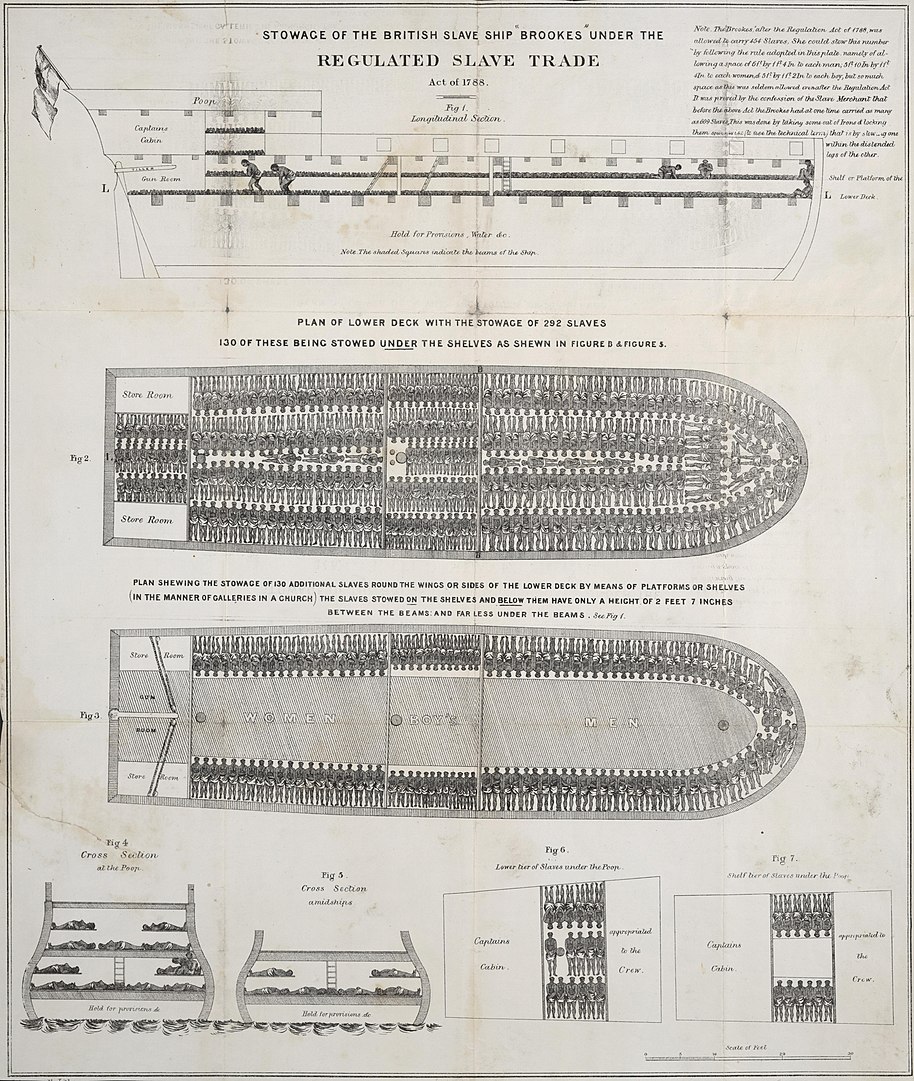

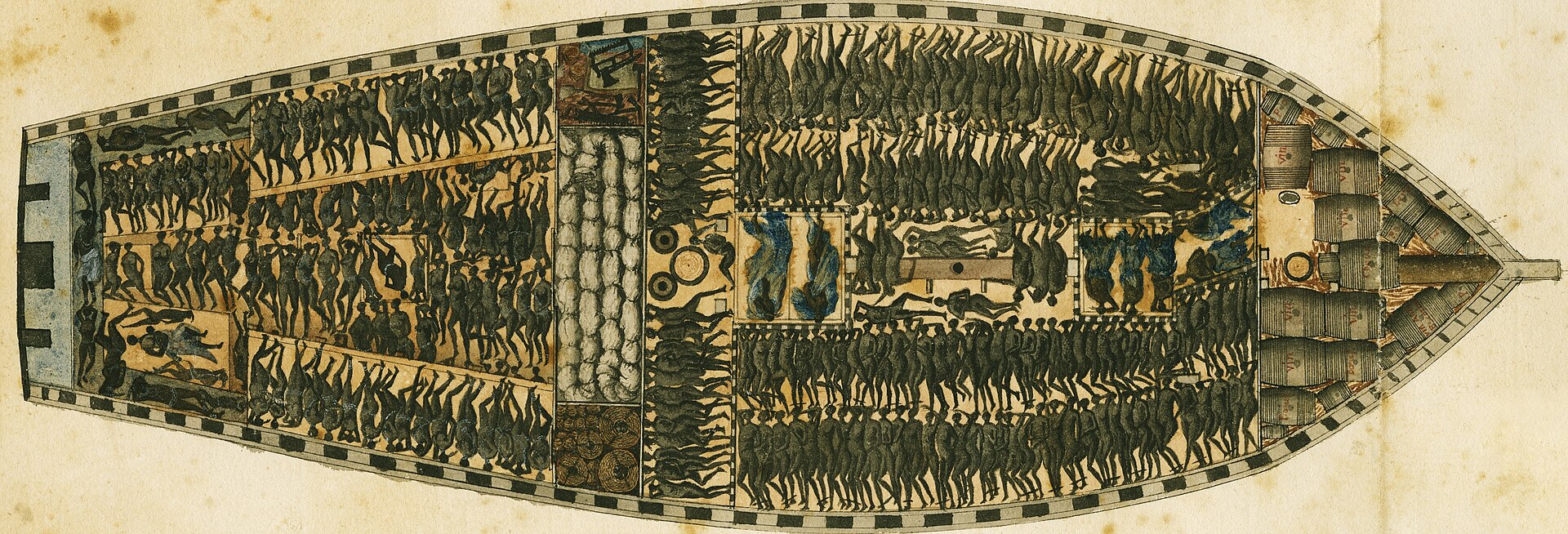

The Middle Passage could last from six weeks to several months, depending on weather and route. Packed and chained, captives endured inhumane conditions. In some compartments, the hold was so low they could only lie down. Cramped together, bodies were compressed against one another. Each enslaved person was allocated about 0.5 square meters on average. At times, the heat became unbearable, causing suffocation, fainting, and death. Trapped in this vile intimacy, captives had no way to relieve or clean themselves, lying in their own excrement, which further infected their wounds and increased the risk of disease.

Women, though separated from men, fared little better. Often kept above deck, they suffered constant sexual violence, rape, and abuse by the crew. The total absence of rights made life a living hell for them. Those who arrived alive, often pregnant from their abusers, became living symbols of the atrocities endured during the crossing.

Disease and mortality

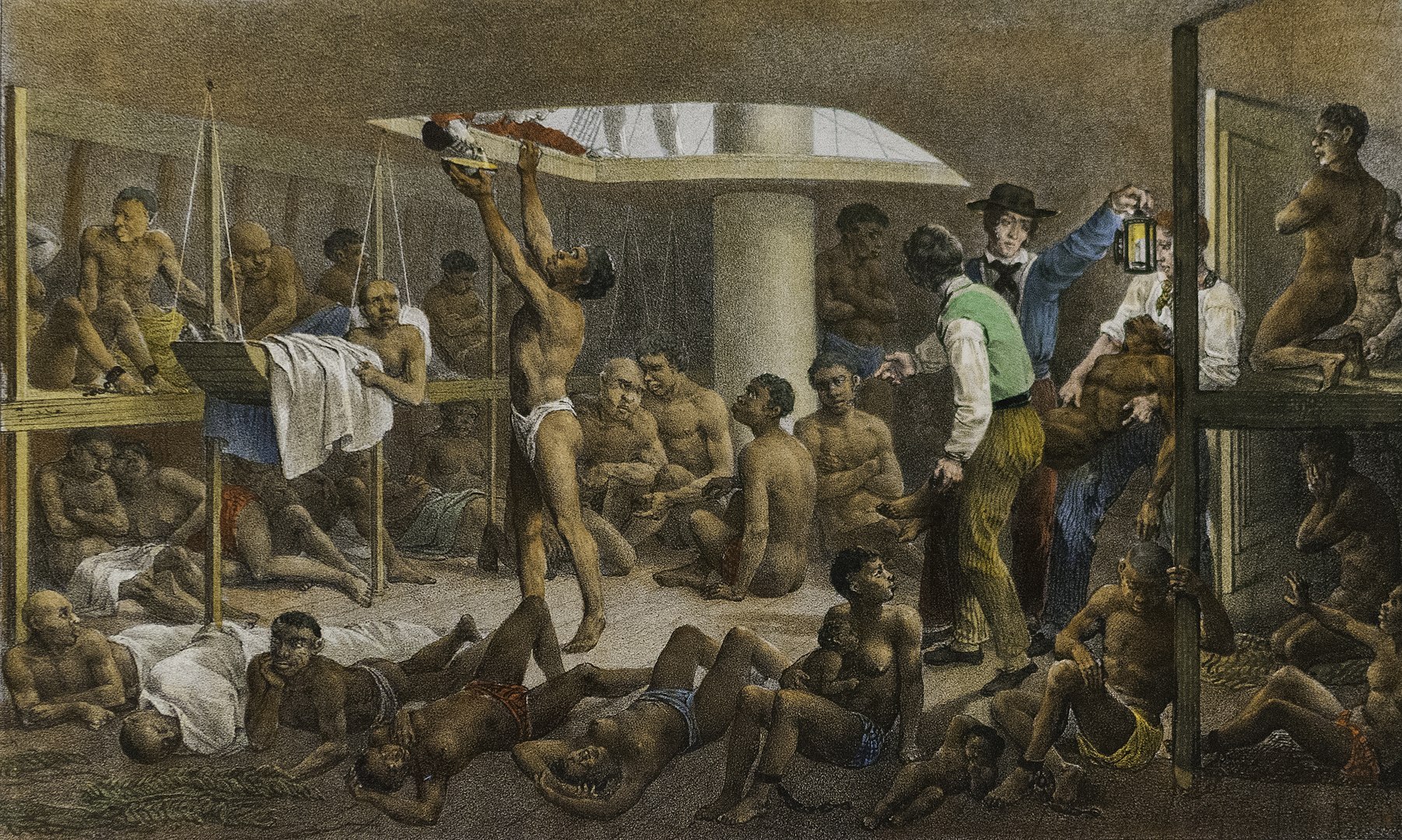

The confinement, lack of hygiene, and malnutrition turned slave ships into epidemic zones where death was a constant threat. Vomiting from seasickness, combined with human waste, created ideal conditions for contagious diseases. Dysentery, typhus, smallpox, and scurvy spread rapidly. Captains, concerned with profitability, often threw the sick and dying overboard to prevent outbreaks.

On average, about 15% of captives never reached the Americas. But for slave traders, these human losses were merely operational costs. The trade operated under a ruthless economic logic: profits were guaranteed by “economies of scale.” The more captives they packed, the more losses they could absorb. This cold calculation turned each voyage into a death machine.

Les répressions et les punitions

For captives who tried to rebel, punishment was swift and merciless. The threat of revolt haunted crews, and captains took no chances. At the slightest hint of insubordination, slaves faced exemplary tortures: thumbscrews crushed their fingers, and the “cat o’ nine tails”—a whip with knotted leather strands and barbs—scarred the already broken bodies of captives.

Faced with suicide attempts, the crew’s cruelty extended further. Many captives tried to starve themselves, hoping to escape their fate. But overseers used the “speculum oris,” a metal device that forced mouths open to feed captives against their will, a painful and humiliating process meant to keep them alive for profit.

Attempts at rebellion and freedom

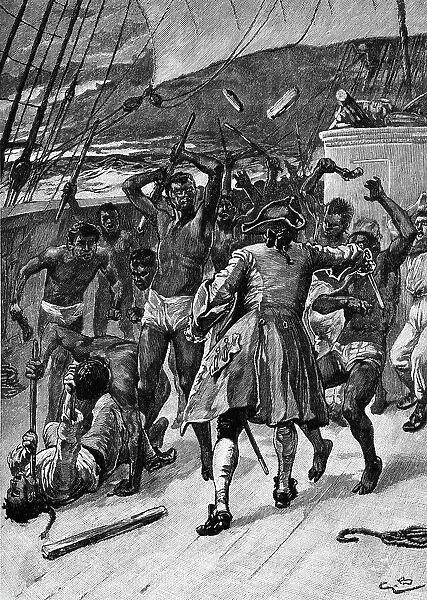

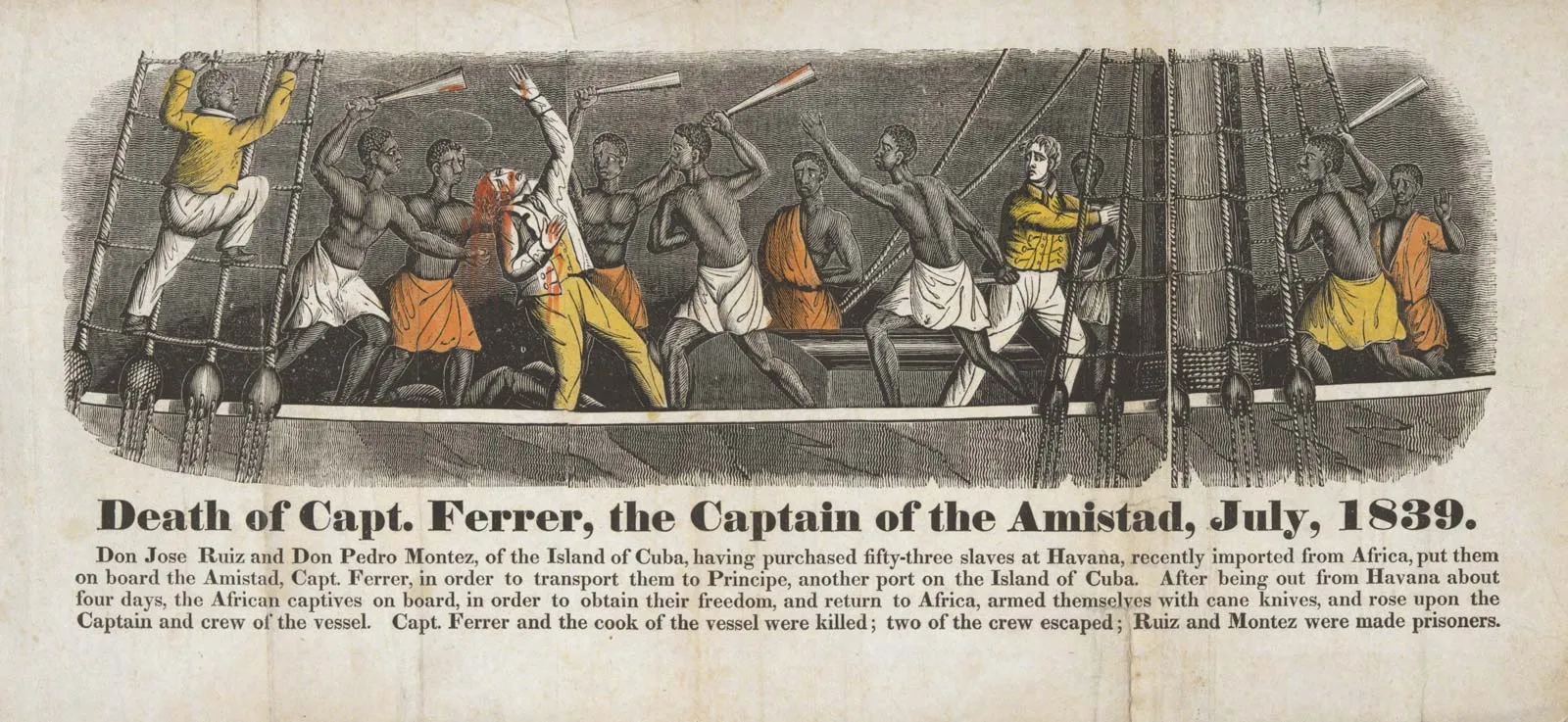

Despite constant oppression, some captives attempted the unthinkable: to revolt and reclaim freedom. Rebellions aboard slave ships were frequent, though rarely successful. Women, often less guarded, sometimes played central roles in these plans. Communicating secretly with men chained below deck, they plotted uprisings. Most revolts were suppressed, followed by cruel reprisals.

One rare successful rebellion occurred aboard La Amistad in 1839, when 53 African captives managed to take control of the ship, killing part of the crew. After weeks adrift, the ship was intercepted by the U.S. Navy. Remarkably, the American justice system eventually recognized the right to freedom for La Amistad rebels, setting a historical abolitionist precedent.

Arrival, a new torment

For those who survived the crossing, the ordeal was far from over. On arrival, captives were sold like commodities, inspected from every angle, forced to stand naked as buyers scrutinized their musculature and teeth like livestock. Torn from their homelands, separated from families, these men and women were sent to plantations, condemned to a life of forced labor, grueling work, and corporal punishment. Some even came to regret surviving the journey, believing death during the crossing might have ended their suffering.

The duty of remembrance

Today, recalling the history of slave ships reminds us of one of humanity’s darkest periods, where greed and indifference reduced millions of human lives to mere commodities. This chapter, etched into collective memory, continues to haunt consciences and raises questions about the legacy of oppression and the reparations owed to those still affected centuries later.

Sommaire

References

- Thornton, John. Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Cohn, Raymond. “Deaths of Slaves in the Middle Passage.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 45, no. 3, 1985, pp. 685–692.

- Hochschild, Adam. Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery. London: Pan, 2006.

- Walvin, James. The Zong: A Massacre, the Law, and the End of Slavery. Yale University Press, 2011.

- Rediker, Marcus. The Slave Ship: A Human History. Viking, 2007.

- Garland, Charles, and Herbert S. Klein. “The Allotment of Space for Slaves aboard Eighteenth-Century British Slave Ships.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 42, no. 2, 1985, pp. 238–239.

- Sadler, Nigel. “The Trouvadore Project: The Search for a Slave Ship and its Cultural Importance.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology, vol. 12, no. 1, 2008, pp. 53–70.

- Sheridan, Richard B. “The Guinea Surgeons on the Middle Passage: The Provision of Medical Services in the British Slave Trade.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 14, no. 4, 1981, pp. 601–625.

- Valentine, Douglas. The Strength of the Pack: The Personalities, Politics, and Espionage Intrigues that Shaped the DEA. Trine Day, 2009.

- Mancke, Elizabeth, and Carole Shammas. The Creation of the British Atlantic World. History Today, 2005.