The Second Congo War, known as the “Great African War,” remains an open wound in contemporary history—a conflict so vast and complex that it often escapes collective memory. Yet, between 1998 and 2003, this war involved nine African nations and dozens of armed groups, resulting in millions of deaths. More than a war, it was a human and political tragedy, a reflection of the scars of colonization and the entanglement of economic, ethnic, and geopolitical interests.

This article does not aim to simplify the unsolvable but to shed light on this often-overlooked chapter of history, raise questions about memory, justice, and accountability, and remind readers that behind every statistic lies a human life.

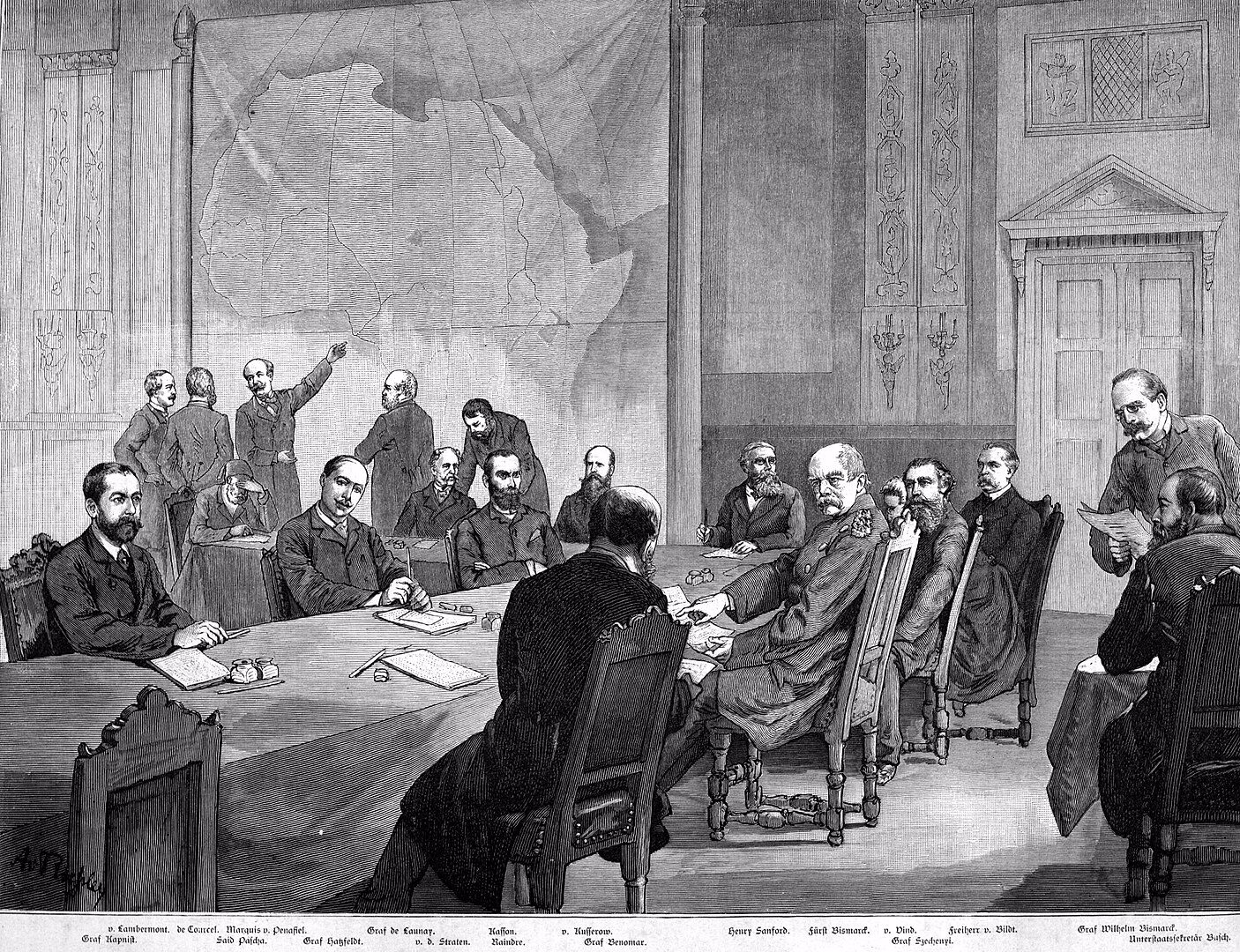

The trap of borders

To understand the Second Congo War, one must revisit the era when Africa’s borders were drawn during the Berlin Conference (1884–1885). These artificial lines, drawn by foreign hands, carved up territories without regard for cultural and ethnic realities. The Congo, a vast land rich in natural resources, became the private property of King Leopold II of Belgium before being turned into a colony in 1908. This history of systematic exploitation left deep wounds.

Upon gaining independence in 1960, the Congo—renamed Zaire under Mobutu Sese Seko—was a giant with clay feet: weak institutions, a fragmented people, and a plundered economy. Mobutu, with Western support during the Cold War, ruled with an iron fist while enriching his inner circle. This corrupt regime collapsed under the weight of ethnic conflicts and regional wars in the 1990s, paving the way for a spiral of violence.

The rwandan genocide and the first Congo War

The Second Congo War is inseparable from the events that shook Rwanda in 1994. In just 100 days, the Hutu-led government orchestrated a genocide that claimed around 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu lives. This massacre triggered a domino effect across the Great Lakes region.

Fearing retaliation, millions of Hutu, including militias responsible for the genocide, fled to Zaire. These refugees quickly became a threat to the newly Tutsi-led Rwandan government under the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF).

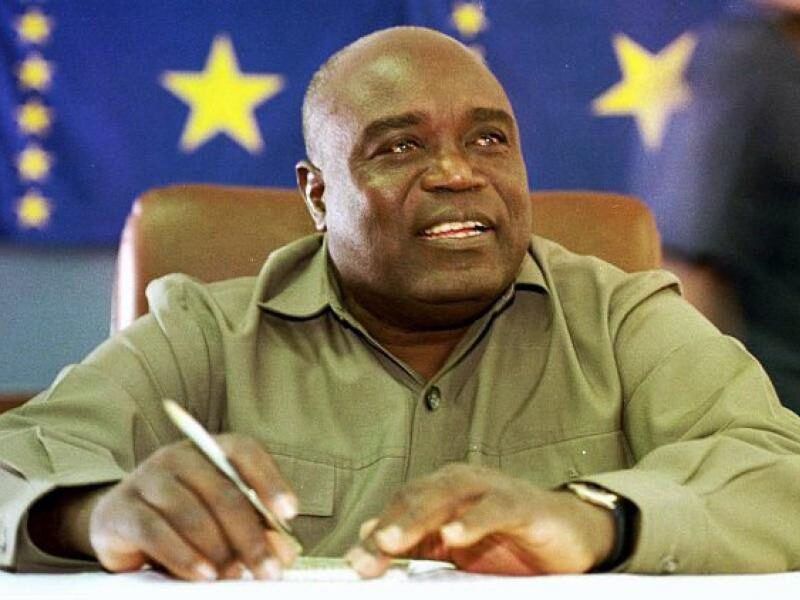

In 1996, Rwanda and its allies, notably Uganda, supported Laurent-Désiré Kabila, a Congolese rebel leader, to overthrow Mobutu. This swift campaign, known as the First Congo War, brought Kabila to power in 1997 but failed to address the country’s structural issues.

Economic interests and ethnic tensions

Once in power, Kabila broke ties with Rwanda and Uganda, fearing their influence. He sought to expel foreign forces and distance himself from the Tutsi factions that had been pivotal in his rise to power. In response, in August 1998, Congolese factions backed by Rwanda and Uganda rebelled against Kabila, igniting the Second Congo War.

However, this conflict extended far beyond Kabila himself. The Congo is a treasure trove of natural resources: copper, gold, diamonds, coltan, and other strategic minerals vital to the global tech industry. These riches attracted the greed of neighboring countries and multinational corporations. In truth, the war was as much a struggle for power as a scramble for resources.

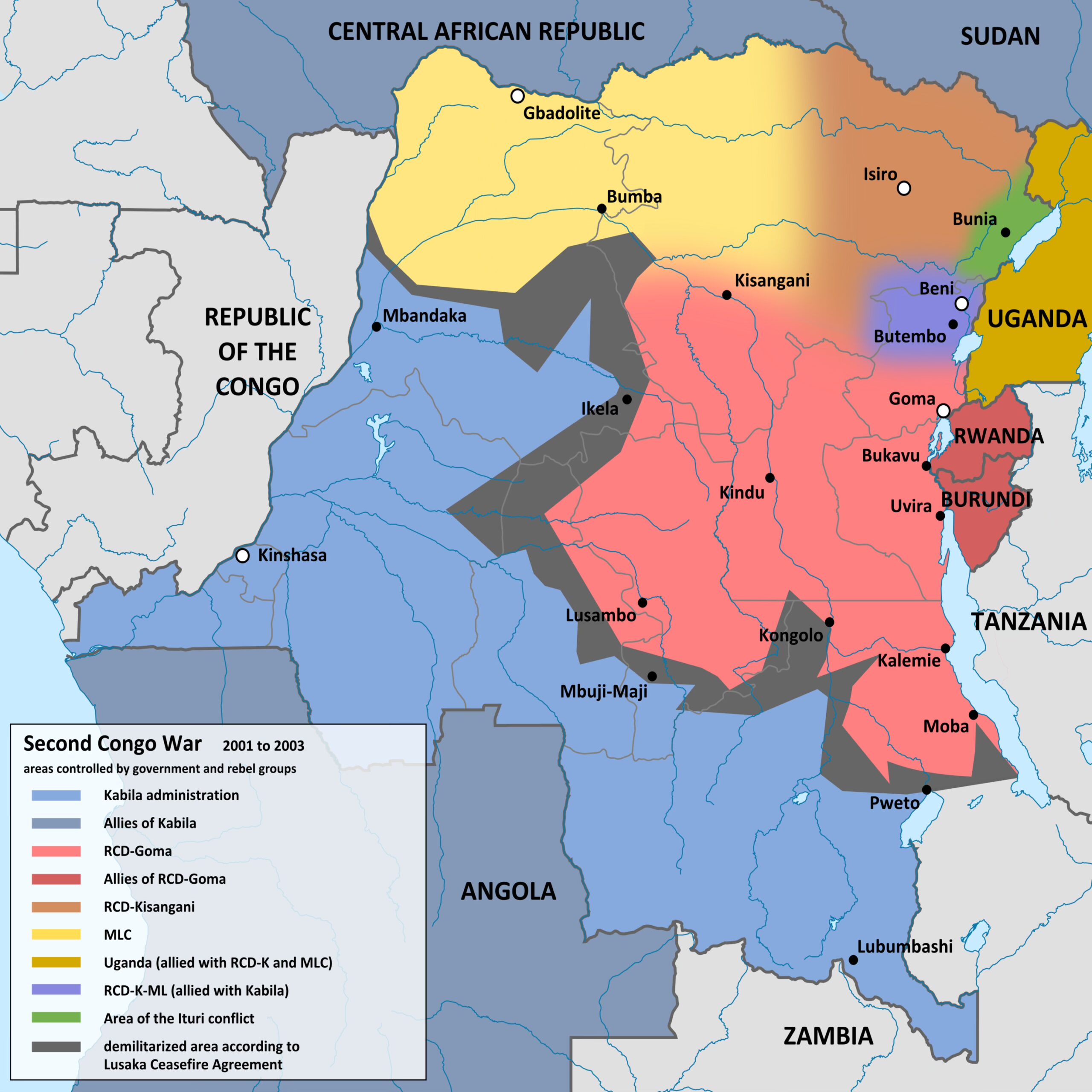

A continental-scale war

At its height, the war involved nine African nations. On one side were Rwanda and Uganda, later joined by Burundi, supporting rebel groups like the Congolese Rally for Democracy (RCD) and the Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC). On the other side, Kabila’s allies included Angola, Zimbabwe, Chad, Namibia, and Sudan, each pursuing their own interests.

Alliances were fluid and often contradictory. For instance, Rwanda and Uganda, once allies, clashed directly in Kisangani in 1999 and 2000, turning the city into a bloody battleground. These disputes highlighted the complexity of a war where the frontlines were as shifting as the actors’ interests.

An unimaginable human cost

The human toll of the Second Congo War is staggering. An estimated 5.4 million people died, mostly from hunger, disease, and forced displacement. This exceeds the death toll of any conflict since World War II. Yet these figures only tell part of the story.

Women and children were the primary victims. Rape was used as a weapon of war on an appalling scale, devastating entire communities. Child soldiers, some as young as eight, were forcibly conscripted and left with lifelong trauma.

Despite this human tragedy, the conflict received little international attention. Why? The war’s complexity, lack of media coverage, and general disinterest in African crises in Western capitals all played a role. But forgetting is itself an act of violence.

A fragile and incomplete peace

The war officially ended in 2003 with peace agreements and the formation of a transitional government that included major rebel groups. However, peace remained fragile. Violence continues to flare in eastern Congo, where armed groups still fight for control of resources.

Joseph Kabila, who succeeded his assassinated father in 2001, ruled the country until 2019, but his tenure was marred by corruption and inefficiency. Hopes for justice for the victims remain slim, and the Congo remains trapped by its contradictions: immense natural wealth and endemic poverty.

Rebuilding memory

The Second Congo War is a tragedy that, in many ways, defies words. How do we tell a story where the suffering is so vast it defies comprehension? How do we honor the millions of lives lost, forgotten by the world?

James Baldwin once wrote, “History is not the past; it is the present. We carry it with us. We are our history.” This war, though officially over on paper, continues to shape the Congo and Africa as a whole. It reminds us that past injustices—colonization, genocides, plunder—cast long shadows over the present.

It is up to both Congolese and global citizens to refuse to forget. For if we turn our backs on this history, we allow it to repeat, again and again.