Seriously, what’s with the obsession with Black superheroes and electricity? It’s like every time a Black hero dons a mask, they’re automatically handed lightning bolts. Black Lightning, Static Shock, Storm (who, let’s face it, spends most of her life summoning storms), not to mention all those obscure characters no one remembers but who are somehow zapping everything in sight.

Coincidence? Not really. Let’s dive into the origins of this trope, from African mythology to lazy stereotypes and legal loopholes. Spoiler alert: it’s equal parts funny and a little depressing.

An omnipresent trope: Electricity as the signature power of Black heroes

Let’s start with the obvious: why electricity? It’s a visually striking power, easy for audiences to grasp. A hero who wields lightning can both impress and intimidate. Narratively, electricity is versatile—it can be used for offense, defense, and even interacting with technology.

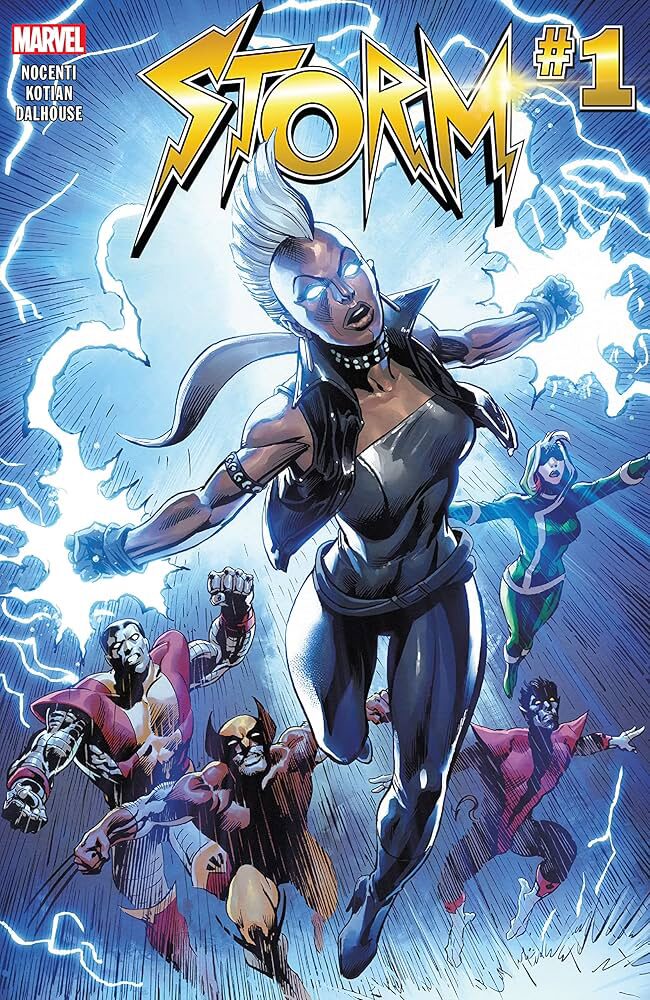

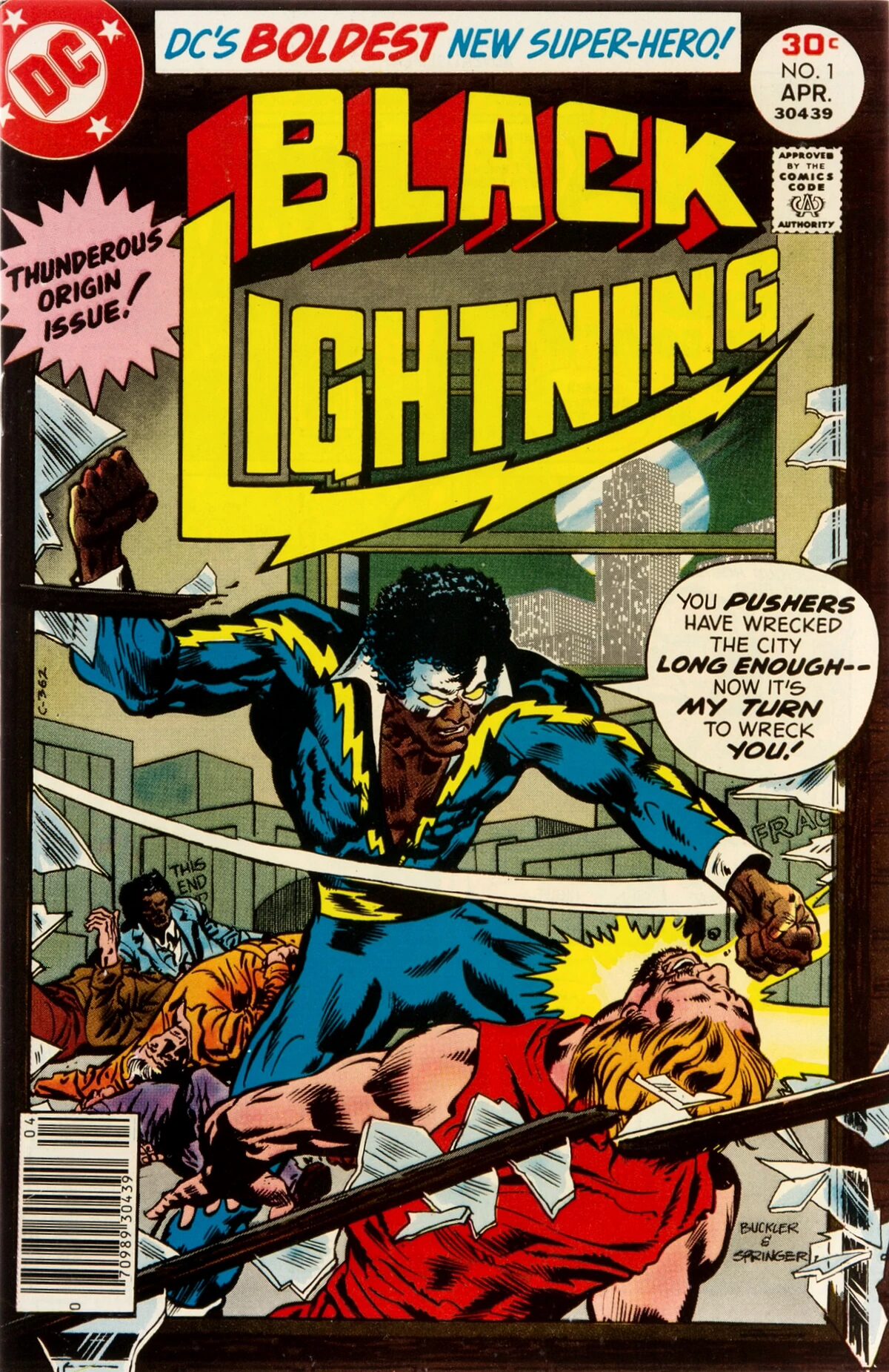

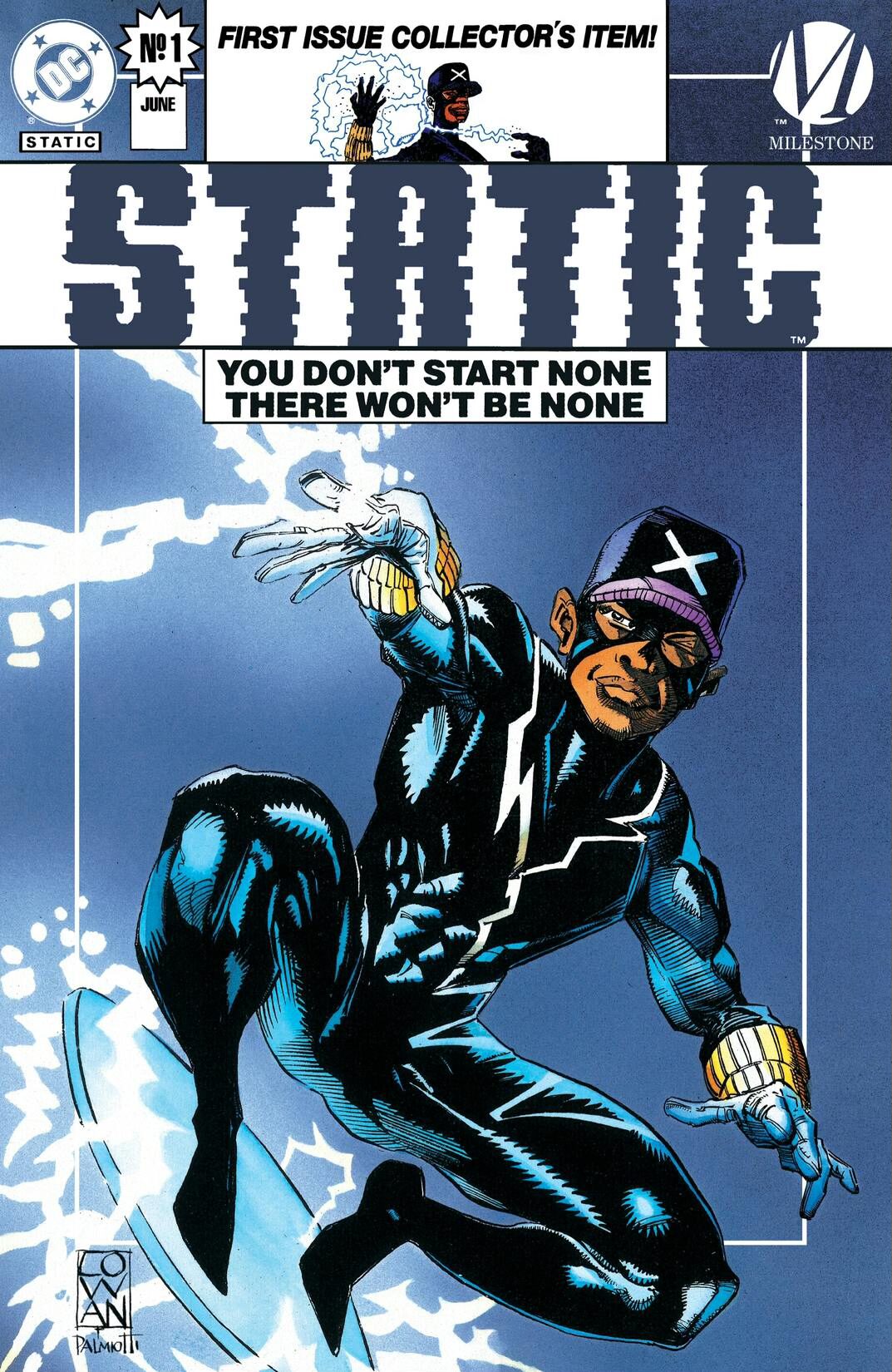

But when you look at the list of Black heroes with electric powers, it becomes clear this trend is no coincidence. Black Lightning, created in 1977, is often credited as the pioneer of this category. Later, Static Shock carried the torch in the 1990s, becoming one of the most popular Black superheroes, especially among younger audiences. Even supporting characters or variations, like Electro (in The Amazing Spider-Man 2) or Aqualad (in Young Justice), somehow end up with electrical abilities.

The issue isn’t that these heroes have electric powers—after all, electricity is cool—but the recurrence limits representational diversity. Why are so many Black heroes tied to this specific energy? Why not other elements like water, fire, or more abstract powers like time manipulation?

A mythological legacy? Not really.

Some argue that this trend may stem from African mythology. It’s true that several traditional stories feature figures capable of wielding lightning. One of the most famous examples is the Mwindo Epic, a Congolese legend where the hero uses lightning to battle enemies and even kill a dragon. In other African traditions, deities like Shango (in Yoruba mythology) are associated with thunder and power.

However, this explanation doesn’t entirely hold up. Electricity isn’t exclusive to African myths. Lightning is universally seen as a symbol of power across cultures. Gods like Zeus (Greece), Thor (Scandinavia), and Lei Gong (China) are all tied to this element.

While African mythology may have inspired some creators, it’s unlikely to be the main reason behind this trend. To understand the phenomenon, we need to look at the modern history of comics.

Black Lightning: The reluctant pioneer

It all started in 1977 with Black Lightning, the first Black superhero at DC Comics with electric powers. Created by Tony Isabella, the character was meant to be a breakthrough for African American representation in comics. But he quickly became more than just a hero—he set the stage for an endless line of electric clones.

What’s crucial to understand is that Black Lightning was born during a time when DC lagged behind Marvel in terms of diversity. While Marvel already had Black Panther and Luke Cage, DC mostly had secondary characters like John Stewart, a Green Lantern. Isabella wanted an original Black hero, and electricity seemed like an obvious choice: visually impactful, easy to understand, and symbolically powerful.

The trouble began when Hanna-Barbera wanted to include Black Lightning in their Super Friends cartoon. Rather than pay Isabella royalties, they created a clone, Black Vulcan—a Black hero with… you guessed it, electric powers. Because why bother being original when you can copy-paste?

Electricity in Naruto: The Raikage and Kumogakure no Sato

The Naruto universe is known for drawing from diverse cultural inspirations, blending Japanese traditions, global mythologies, and modern elements. Within this context, Kumogakure no Sato (the Village Hidden in the Clouds) is home to ninjas specializing in electricity-based techniques. It’s also notable for featuring Black characters like the Third Raikage, Fourth Raikage, and Darui.

These characters often combine electric powers with brute strength, showcasing both their physical prowess and mastery of lightning. For instance:

- The Third Raikage is legendary for his defensive technique, Raiton Chakura Mōdo (“Lightning Release Chakra Mode”), and his offensive move, Jigokuzuki (“Hell Stab”).

- The Fourth Raikage uses lightning to enhance his speed and physical power to superhuman levels.

- Darui combines electricity with water for strategic attacks.

While Kumo’s lightning affinity aligns with the element’s associations with power and speed, it also reinforces stereotypes that Black characters are always linked to raw, physical strength rather than intellectual or spiritual abilities. ou physiques, plutôt qu’à des capacités intellectuelles ou spirituelles.

The domino effect: Where it all went wrong

Black Vulcan opened the floodgates for a slew of electrified Black characters. Why? Because electricity is simple, effective, and visually appealing. Creators didn’t want to reinvent the wheel, and by constantly recycling the concept, it became a trope.

Then came Static Shock, a teenage hero with electric powers, created by Milestone Comics in 1993. Static added depth by tackling social issues like racism and urban violence. Yet his success reinforced the idea that Black superheroes must have electric powers.

Need another example? Consider Soul Power, a character created to replace Black Lightning in the Static Shock animated series (because DC still didn’t want to pay Tony Isabella). Seriously, how many times can the same concept be recycled before it becomes absurd?

A lazy stereotype or an unconscious strategy?

Giving electric powers to Black superheroes might seem harmless. After all, it’s just a power, right? But when viewed collectively, it highlights a deeper issue: a limited vision of what it means to be a Black hero. Creators, often white, associate electricity with raw, untamed power—a perspective that reflects unconscious racial stereotypes.

It’s as if Black heroes are confined to a role: the badass, unpredictable figure, but rarely the strategist or charismatic leader. That’s a problem. Why not explore other types of powers? Why not create Black heroes who embody something other than destructive force?

Miles Morales: Redefining the trope

Thankfully, some characters have managed to transcend this cliché. Take Miles Morales, the modern iteration of Spider-Man. Yes, he has electric powers, but that’s just one aspect of his character. Miles is also a clever, creative, and deeply human teenager. He proves that Black superheroes can be more than just lightning machines.

But for every Miles Morales, there are countless electric-powered heroes with little depth. That’s where the real issue lies: an industry struggling to break out of its comfort zone, even as it claims to champion diversity.

So, what’s next?

The goal isn’t to ban Black superheroes with electric powers but to diversify representation. Black heroes deserve varied stories, powers, and perspectives. Electricity is cool, but it’s time to move on. Why not a Black hero who controls dreams? Or manipulates gravity? The possibilities are endless.

Ultimately, comics are a mirror of society. If that mirror keeps reflecting the same clichés, maybe it’s time to shatter it and rebuild. Because while electricity can light up a room, it can also power change. So when will we see a Black hero who electrifies minds, not just enemies?

Bibliography and references

- Malkia: A dive into mythical Africa

The two volumes of Malkia, published by Nofi Editions, explore a fantastical Africa blending myths, heroism, and adventure. This work highlights Afro-descendant narratives in a contemporary and engaging setting. Available from: Nofi Editions. - Black Lightning and the legacy of comics

Created in 1977 by Tony Isabella, Black Lightning played a crucial role in representing African Americans in comic books, becoming a pioneer among original Black superheroes at DC Comics. For archives and additional details, consult: DC Comics Archives. - Static shock and Milestone Comics

Introduced in 1993 by Milestone Media, a subsidiary of DC Comics, Static Shock became iconic thanks to an animated series aired in the early 2000s, popularizing this teenage hero and his fight against social injustices. For more information, see: The Milestone Universe: A Revolution in Comics. - Raikage and Kumogakure in Naruto

The Hidden Cloud Village (Kumogakure), featured in the manga Naruto by Masashi Kishimoto, draws inspiration from various global cultures. It showcases powerful Black characters, including the Raikage, masters of electricity. For detailed information, see: Masashi Kishimoto, Naruto Databook, Shueisha. - African mythology and electricity

In African stories, figures like Shango (Yoruba) and Mwindo (Congolese mythology) highlight the connection between lightning and power. These stories enrich global imagination around electricity. Source: Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher, African Myths and Legends. - The role of copyright in comics

The story of Black Vulcan, created to circumvent royalties owed to Tony Isabella, reflects the economic and legal dynamics that have influenced the comic book industry. This story is detailed in several interviews and analyses, particularly in: Comic Book History of Black Superheroes, Smithsonian Editions. - Diversity in modern comics

Characters like Miles Morales in Spider-Man illustrate an evolution toward more nuanced and varied representation of Black superheroes while maintaining a connection to electric powers. For an in-depth analysis, see: Jeffrey A. Brown, Superheroes and Identity Politics.