Discover the little-known history of Afro-Iranians, descendants of slaves and African immigrants who have settled in Iran for centuries. Caught between African traditions and Persian culture, their unique journey embodies the resilience of a community oscillating between erased memory and rediscovered identity.

The history of Africa and its diasporas stretches beyond continents and visible borders, as shown by the Afro-Iranians, a group deeply rooted in southern Iran through provinces such as Hormozgan, Sistan, Baluchistan, and Khuzestan. Composed of descendants of slaves brought from East Africa via the eastern slave trade, Afro-Iranians are today a minority rich in cultural heritage, blending Shia Islam, African, and Persian traditions. Although often erased from collective memory, their existence symbolizes the resistance and adaptation of a people shaped by exile and survival.

Origins and routes of the Eastern Slave Trade

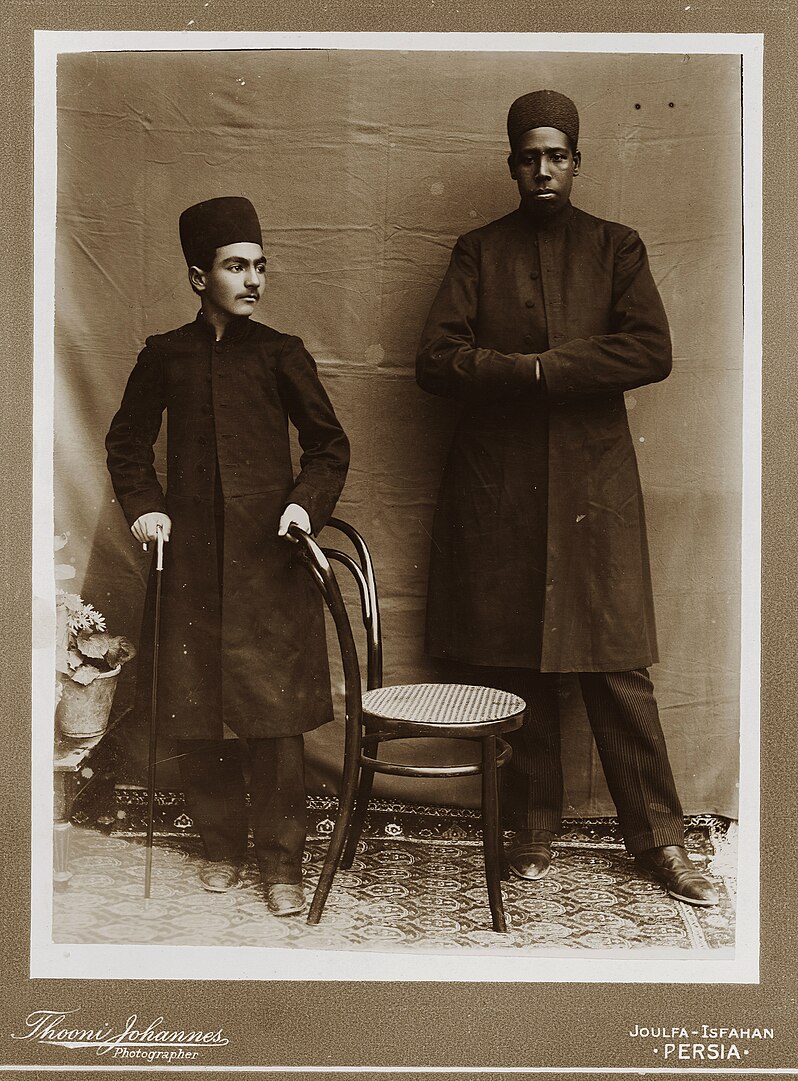

A rare Safavid oil painting depicting an African soldier, Persia, Isfahan, circa 1680-90.

Afro-Iranians, also known as “Siya” (meaning “Black” in Persian) or “Bambasi” for some groups, trace their origins to the Eastern slave trade. Beginning in the 9th century, trade routes linked East Africa to the Middle East, transporting thousands of African men, women, and children to distant lands such as the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian Peninsula, and Persia, present-day Iran. While the Atlantic slave trade is well-documented and recognized, the Eastern slave trade, although less visible in Western historical accounts, is no less significant. For centuries, Africans were exchanged, primarily from the Swahili coast, by Arab, Portuguese, and Persian merchants.

A late practice and cultural traces

The enslavement of Afro-Iranians persisted well after Western abolitions. The 19th century, in particular, marked an intensification of slave imports into Iran, where wealthy Persian families, especially under the Qajar and Safavid dynasties, employed African slaves in aristocratic households for domestic tasks, sometimes alongside Circassian or Eastern European slaves. Black slaves, mainly women and children, were integrated into households, where they became servants or concubines. It was only in 1848, under British pressure, that Mohammad Shah Qajar signed a firman (decree) officially banning the slave trade, although slavery persisted unofficially until the early 20th century. Even today, musical practices like bandari reflect the African roots of these Iranians of sub-Saharan origin, blending African rhythms and Persian songs.

A struggle for visibility

Since the 2020s, a movement for identity rehabilitation has emerged, embodied by collectives like the Collective for Black Iranians, whose mission is to raise visibility for the Afro-Iranian community. The collective aims to bring Afro-Iranians to public attention, highlighting their contribution to Iranian culture and identity as well as the discrimination they still face. Inspired by movements like Black Lives Matter, the collective advocates for the recognition of Iranian Blackness and for the acceptance of the country’s racial diversity.

Activists such as Alex E. Eskandarkhah fight to reverse the negative connotations associated with the term “Siya” and transform this designation into a symbol of affirmation and pride. Through their work, Afro-Iranians assert their place in Iran’s “tapestry,” seeking to deconstruct misconceptions, such as the idea that Afro-Iranians are “black because of the sun.” This type of myth has been reinforced by a culture of denial of slavery, which researchers like Beeta Baghoolizadeh explain as being influenced by the “Aryan myth”: a popular belief inherited from Persian history that “true” Iranians never practiced slavery nor inherited African lineage.

Afro-Iranian tradition and identity

Despite the obstacles, Afro-Iranians continue to preserve their cultural heritage through ancestral practices like the Zārritual, a healing ritual primarily practiced in southern Iran, in Sistan-Baluchistan, and in the Hormozgan region. Zār, an inheritance of African spiritual beliefs, involves songs and dances intended to exorcise evil spirits. Musicians like Saeid Shanbehzadeh, a Black Iranian artist, perpetuate this musical and cultural memory, emphasizing the close ties that bind Afro-Iranians to their African roots while incorporating these practices into contemporary Persian culture.

An unacknowledged yet indelible legacy

Although largely absent from school textbooks and media, the Afro-Iranian community is a living testament to Persian history, transcending ethnic and racial boundaries. In exploring their past, Afro-Iranians demonstrate courage, transforming the stigma of a painful past into a cultural and identity-driven strength. Their journey is undeniable proof of humanity’s capacity to overcome adversity and take control of its destiny.

Sommaire

Notes and references

- Olivier Favier, « Les Africains-Iraniens : une identité taboue », RFI, 17 juillet 2020.

- Michelle Woodward, « Writing Ourselves into Existence with the Collective for Black Iranians », Middle East Research and Information Project, 29 juin 2021.

- Beeta Baghoolizadeh, « The Afro-Iranian Community: Beyond Haji Firuz Blackface, the Slave Trade, & Bandari Music », Ajam Media Collective, 20 juin 2012.

- Gwyn Campbell, The Structure of Slavery in Indian Ocean Africa and Asia, Routledge, 2003.

- Tazmini, Ghoncheh, « The Persian–Portuguese Encounter in Hormuz: Orientalism Reconsidered », Association for Iranian Studies, vol. 50, no. 2, Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Astrid Krivian, « Saeid Shanbehzadeh : “Comme mes ancêtres africains, je suis en exil” », Le Point, 1er janvier 2018.

- UNESCO, Fugitive Slaves, Asylum and Manumission in Iran (1851 – 1913), 2010.