October 30 spans history like a red thread, linking stories of insurrections, injustices, and emancipatory struggles that echo the collective memory of Africa and its diaspora. From Nat Turner, captured after a slave revolt, to Lobengula, King of Matabeleland, and the recent democratic struggles in Burkina Faso, this day reminds us how resistance, sacrifice, and courage shape the history of the African continent and its children worldwide.

Historical events

October 30, 1831: Capture of Nat Turner

In 1831, in Southampton County, Virginia, Nat Turner, a slave and charismatic preacher, led one of the most significant slave revolts in the United States in a daring quest for freedom and justice. After weeks of secret planning, Turner launched the insurrection in August, leading a group of slaves who killed several dozen white slave owners. Though brutal, this act became a symbol of resistance to slavery and provoked violent reactions from authorities.

Turner managed to evade capture for six weeks, hiding in Southampton County’s backwoods. During this time, his wife, Cherry, was captured, beaten, and tortured by authorities attempting to extract information about his location and future plans. Under pressure and violence, she was reportedly forced to surrender documents related to the rebellion.

Finally, on October 30, 1831, Turner was found by a farmer, Benjamin Phipps, hiding in a hollow formed by a fallen tree and covered in branches. Captured, he was imprisoned in Jerusalem, Virginia, the following day. During his imprisonment, Turner confessed his actions and the motivations behind the revolt to Thomas R. Gray, a lawyer and slavery advocate, who later published an account of their conversations. Turner was executed shortly afterward, but his struggle continues to inspire movements for justice and equality.

October 30, 1888: The Rudd Concession

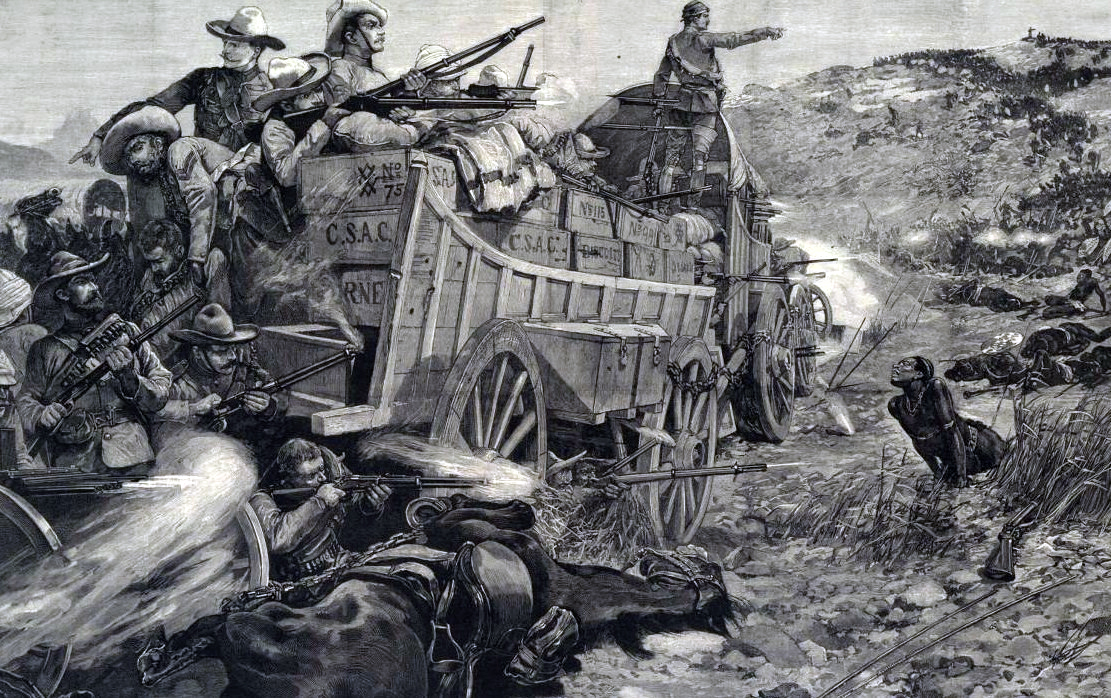

On October 30, 1888, King Lobengula of Matabeleland (present-day Zimbabwe) signed a treaty known as the “Rudd Concession,” granting exclusive mining rights over his territory to Charles Rudd, Francis Thompson, and James Maguire, under Cecil Rhodes’ direction. In exchange for this exclusive right, Lobengula received a sum of money and a substantial supply of arms. Though signed with the approval of some Matabele chiefs, Lobengula quickly contested the treaty, feeling betrayed by the true intentions of the British.

The agreement enabled Rhodes to seek a royal charter, officially granting control of Matabeleland to the British South Africa Company, initiating a process of occupation that would lead to the foundation of Rhodesia. Despite several attempts to rescind the treaty by sending envoys to Queen Victoria, Lobengula was unable to halt the colonial momentum. This concession became a foundation for British expansion in Southern Africa, marking the beginning of the end for the Matabele kingdom.

Today, this episode remains a symbol of the tactics used by colonial powers to seize African wealth and lands, often at the expense of local sovereignties.

October 30, 1963: Ceasefire between Algeria and Morocco

Tensions between Morocco and Algeria peaked in 1963, marked by a series of unsuccessful diplomatic efforts to establish a lasting ceasefire. The first initiative came from Tunisian President Habib Bourguiba, who sought to initiate dialogue between the two nations. However, this mediation quickly failed. Subsequently, a summit was organized in Marrakech from October 15-17 under Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie’s leadership, who was then visiting North Africa. Despite efforts, this negotiation attempt also proved futile.

Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser proposed a North African summit. However, his military support for Algeria undermined his position as a mediator in Morocco’s eyes, making his initiative untenable. Meanwhile, the Arab League, influenced by Egypt, offered mediation, which Morocco rejected, deeming it too favorable to Algiers.

In the face of these failures, Haile Selassie and Malian President Modibo Keita managed to convince both parties to meet at a peace conference in Bamako on October 29-30. An agreement was finally reached, calling for a ceasefire effective November 2 and establishing an international commission to oversee the cessation of hostilities.

2014: Uprising in Burkina Faso

On October 30, 2014, Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou, became the scene of an unprecedented uprising. Thousands of protesters gathered in the suburbs, converging on symbols of power in a mobilization of unmatched intensity. Police attempted to disperse the crowd with tear gas, but the popular pressure was so great that protesters broke through barriers and set several buildings on fire, including the Congress for Democracy and Progress headquarters, the party of President Blaise Compaoré.

Among the targets of popular anger was also the Kosyam presidential palace, defended by the presidential guard. Meanwhile, nearly 1,500 protesters stormed the National Assembly, where deputies had just begun a session. Evacuated in extremis, parliamentarians left behind burning offices and charred documents. Deputy Ablassé Ouedraogo, a witness to the scene, declared: “Protesters are not listening to anyone; things are out of control.”

The violence escalated when the presidential guard opened fire with live ammunition to protect the home of François Compaoré, the president’s brother, killing three civilians. Protesters also stormed the headquarters of Burkina Faso’s Radio and Television Broadcasting, posing with the news anchor as soldiers deployed around the building to try to secure it. Meanwhile, phone networks and 3G were blocked, paralyzing communication.

In other cities, the unrest quickly spread. In Bobo-Dioulasso, the country’s second-largest city, protesters toppled statues and ransacked ruling party offices. Ouahigouya in the north also saw similar scenes of violence. Ouagadougou airport closed, suspending all flights.

Amid the crisis, army chief General Honoré Traoré imposed a national curfew and dissolved the National Assembly, announcing the formation of a transitional government. In response, Blaise Compaoré addressed the nation, mentioning the possibility of talks and paving the way for political transition.

Key figures

Nia Long, icon of african-american cinema

Born October 30, 1970, in Brooklyn, New York, as Nitara Carlynn Long, Nia Long is a leading figure in American cinema and television. Of Trinidadian, Barbadian, and Grenadian descent, she is the daughter of Talita Long and Doughtry “Doc” Long, two engaged educators. From an early age, she displayed an affinity for the arts, practicing dance, gymnastics, and singing. Graduating in 1989, she quickly launched her acting career with the help of her mentor, Betty A. Bridges.

Nia Long achieved early success portraying strong and diverse characters on TV and in movies. She gained recognition in iconic productions such as Boyz N the Hood (1991) and the series The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, where her role as Lisa Wilkes endeared her to audiences. She continued to succeed in notable films, such as the popular comedy Big Momma’s House (2000) and The Best Man (1999), in which she portrayed complex characters with finesse.

Her television talent was also recognized, as she received several NAACP Image Awards for her role in Third Watch, consolidating her status in American TV. Successfully alternating between comedic, dramatic, and even fantasy roles, she demonstrates rare versatility that continues to inspire. Today, Nia Long is a respected figure in African-American cinema, symbolizing talent and resilience and inspiring future generations with her memorable performances and remarkable career.

Warith Deen Mohammed, A reformist leader

Born October 30, 1933, in Hamtramck, Michigan, Warith Deen Mohammed, whose real name was Wallace Delaney Muhammad, was the son of Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam (NoI). Influenced by his father’s fame and teachings, he grew up in an organization that advocated a separatist vision and a radical interpretation of Islam. However, from a young age, Warith Deen developed a more orthodox understanding of the Muslim faith, which led him to distance himself from the NoI ideology.

Upon his father’s death in 1975, Warith Deen Mohammed inherited the NoI leadership. He undertook profound reform, transforming the organization into a Sunni, pacifist movement that rejected Black nationalism and unorthodox doctrines. This bold transformation led to a break with Louis Farrakhan, who reestablished the NoI in 1981, preserving his father’s doctrines. Warith Deen Mohammed, for his part, continued to promote a Sunni Islam that emphasized racial harmony and the integration of African-Americans into American religious and social life.

Until his death on September 9, 2008, Warith Deen Mohammed influenced the American Muslim community by decentralizing mosques and advocating harmonious integration within American society. As an influential religious leader, he became a symbol of reform and openness, embodying a peaceful and tolerant Islam. His legacy endures, inspiring generations of Black American Muslims.

Jam Master Jay, DJ of Run-DMC

Born Jason William Mizell on January 21, 1965, in Brooklyn, New York, Jam Master Jay was an iconic figure in hip-hop culture. A talented child, he learned several instruments, including the trumpet and bass, before dedicating himself to DJing in the 1970s. In 1982, his meeting with Joseph “Run” Simmons and Darryl “D.M.C.” McDaniels led to the formation of Run-D.M.C., a group that would redefine hip-hop and achieve international fame. Together, they made history with hits like Raising Hell and contributed to popularizing the genre by blending rock with hip-hop.

Beyond music, Jam Master Jay left a lasting impact by founding Jam Master Jay Records in 1989, where he launched the group Onyx. In 2002, he established Scratch DJ Academy in Manhattan, a center dedicated to young DJing enthusiasts, continuing his commitment to nurturing hip-hop culture.

On October 30, 2002, at the age of 37, Jam Master Jay was murdered in his studio in Jamaica, Queens. This shocking murder remained unsolved for nearly two decades, leaving the music community in mourning. In 2020, two suspects were finally charged, but the mystery and sadness surrounding his death persist. Despite this tragic fate, Jam Master Jay’s legacy endures, inspiring generations of musicians and underscoring Run-D.M.C.’s indelible impact on the global stage.

Summary

References

- Turner, Nat. Confessions of Nat Turner. Richmond Enquirer, 1831.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. Coloniality of Power in Postcolonial Africa: Myths of Decolonization. CODESRIA, 2013.

- Ayoob, Mohammed. The Third World Security Predicament: State Making, Regional Conflict, and the International System. Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1995.

- Hagberg, Sten. Burkina Faso: Local Dynamics of Democratization. Nordic Africa Institute, 2002.

- Chang, Jeff. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. St. Martin’s Press, 2005.

- “Jam Master Jay, Hip-Hop Pioneer of Run-DMC, Dies at 37,” The New York Times, October 31, 2002.

- Rose, Tricia. Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Wesleyan University Press, 1994.

- Curtis IV, Edward E. Muslims in America: A Short History. Oxford University Press, 2009.