The issue of financial reparations for the descendants of Black slaves remains controversial, although regularly discussed in debates about the transatlantic slave trade. Ironically, it is little known that British slave owners were immediately compensated under the Slave Compensation Act of 1837.

The compensation of slave owners: a historical privilege

In the national narratives of Western countries with a history of slavery, which many descendants of slaves naively present as universal historical truths, the end of the transatlantic slave trade is often depicted as the result of a surge of humanism and justice by great white men who put an end to this crime against humanity.

However, a few questions arise: What kind of ‘hero’ worthy of the name would pay criminals to stop their wrongdoings? What kind of justice would maintain former victims in a position of disadvantage to benefit their former oppressors without compensating them?

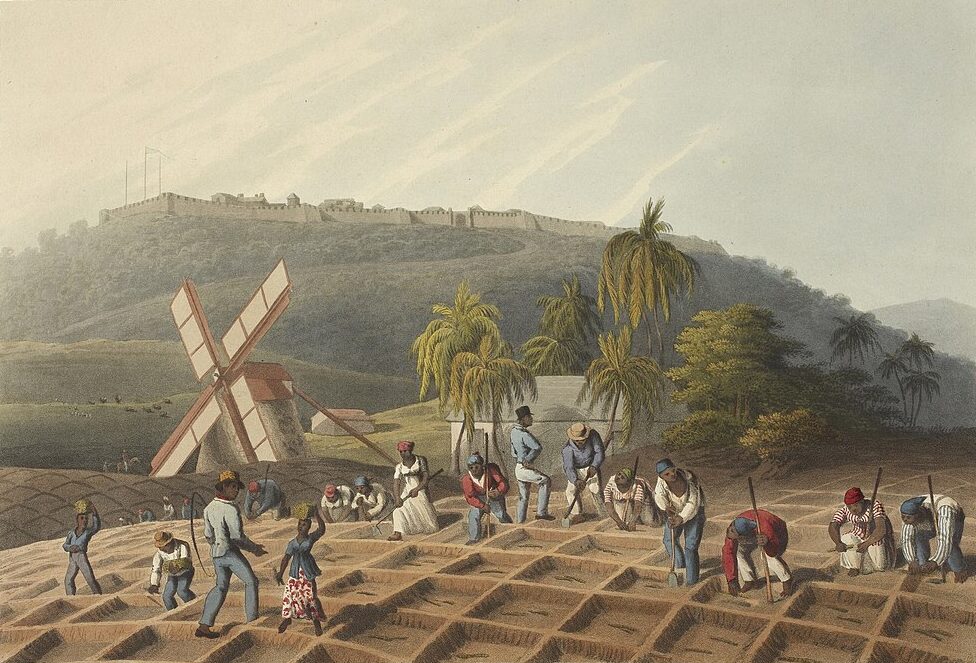

In the British West Indies1, where the slave-based economy significantly contributed to the metropolitan economy, the emancipation of slaves led to compensation from the British state. The compensation of 20 million pounds (estimated at around 76 billion pounds in today’s economy) was not intended for the victims but for those who were ‘victims’ of its abolition.

Former slaves received neither money nor property, with their only prospect being employment at lower wages by their former masters.

In her book The Economics of Emancipation, K.M. Butler highlights a long list of British slave-owning bankers and the astonishing amounts of compensation they received:

- £93,965 for W., R. & S. Mitchell

- £59,545 for W., G. & S. Hibbert

- £38,247 for Judah & Hannah Cohen

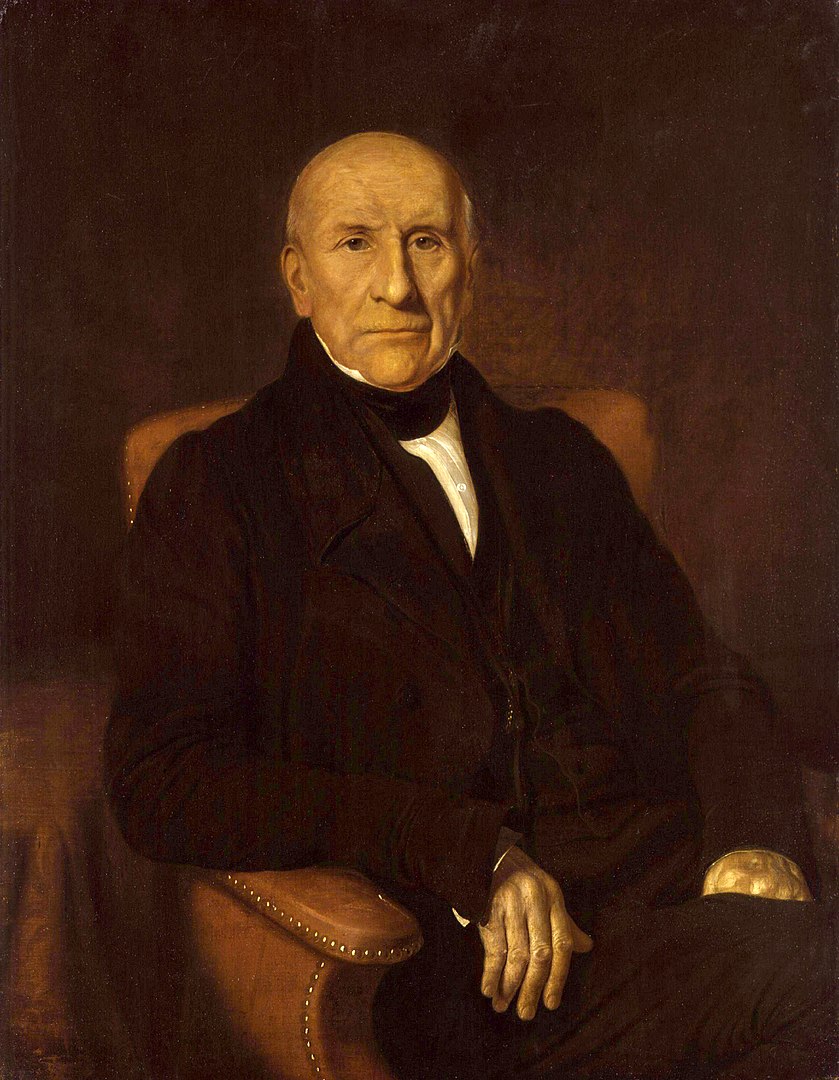

These new earnings were largely reinvested in the British economy, as illustrated by the case of the slave-owning landowner John Gladstone2.

John Gladstone, a British landowner and politician, is a notable example of how slave owners were compensated after the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. Gladstone owned vast sugar plantations in Jamaica and Demerara (now Guyana). He was also president of the West India Association, an influential organization representing the interests of British West Indian planters.

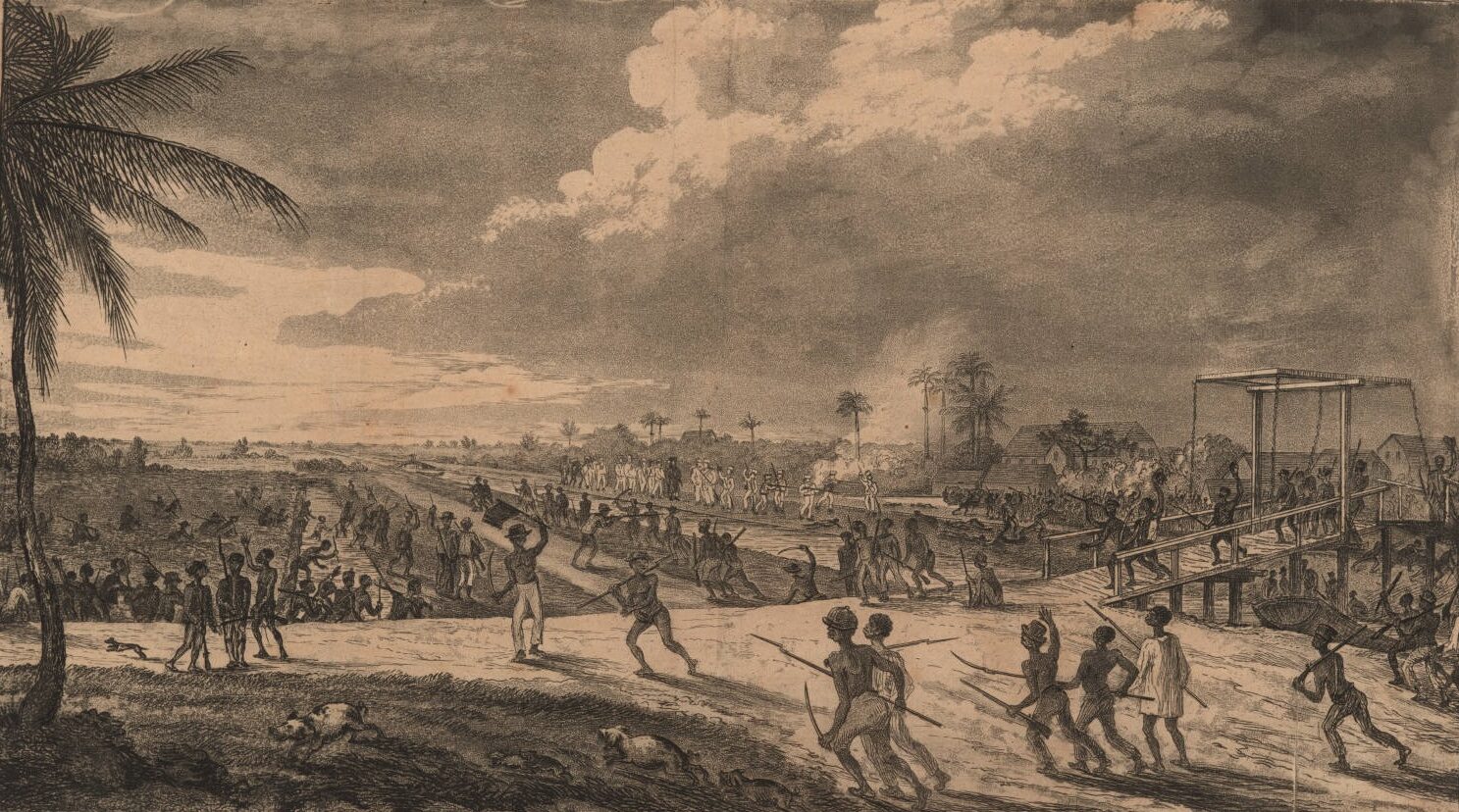

The Demerara Rebellion of 18233, a massive slave uprising, broke out on Gladstone’s plantation in Demerara-Essequibo, in what is now Guyana. This revolt, led by Jack Gladstone4, a slave working as a cooper on John Gladstone’s “Success” plantation, was brutally repressed by the colonial army and militia. Jack Gladstone, who bore the name of his master following the convention of the time, became a symbolic figure of resistance against the horrors of slavery.

With the help of his son William, John Gladstone received a substantial compensation following the abolition of slavery, under the Slave Compensation Act5. This legislation followed the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act6, which ended slavery in the British Empire.

Gladstone’s claim was the largest of all those made to the Slave Compensation Commission. He owned 2,508 slaves in British Guyana and Jamaica and received a payment of £106,769 (equivalent to about €14,487,707.50 in 2023). Gladstone’s claims were spread over several plantations, significantly increasing the total value of his compensation.

The compensation of slave owners and the lack of reparations for slaves raise crucial questions in the contemporary debate on reparations. The fact that slave owners were compensated but not their direct victims constitutes a historical injustice that continues to fuel calls for reparations today.

Supporters of reparations argue that compensatory measures are necessary to correct historical injustices and the persistent socio-economic disadvantages. They advocate for investments in education, healthcare, and economic development in communities descended from slaves to rectify the structural inequalities inherited from the past.

However, opponents of reparations point to several obstacles. They highlight the complexity of determining who should be compensated and to what extent. Additionally, there is political and social resistance to the idea of allocating public funds for financial compensations, fearing that it could rekindle racial tensions.

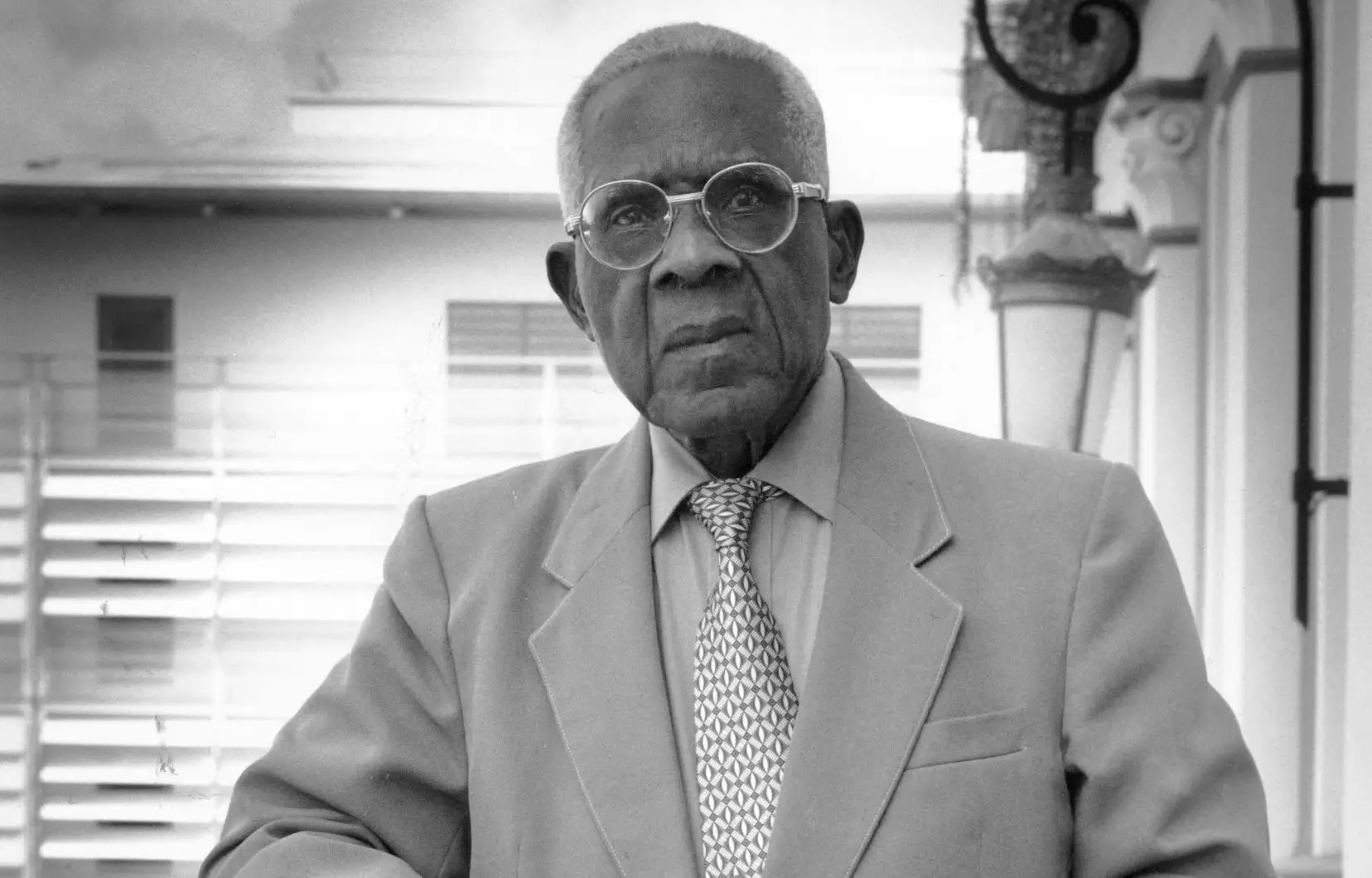

When asked about this issue, Aimé Césaire said:

“IT IS ALREADY VERY IMPORTANT THAT EUROPE HAS COME TO ADMIT THE REALITY OF THE SLAVE TRADE, THIS TRAFFICKING OF HUMAN BEINGS THAT CONSTITUTES A CRIME. BUT I AM NOT IN FAVOR OF REPENTANCE OR REPARATIONS.

THERE IS EVEN, IN MY VIEW, A DANGER TO THIS IDEA OF REPARATIONS. I WOULD NOT WANT A DAY TO COME WHEN EUROPE SAYS: ‘WELL, HERE’S THE TICKET OR THE CHECK, AND LET’S NOT TALK ABOUT IT ANYMORE!’

THERE IS NO POSSIBLE REPARATION FOR SOMETHING IRREPARABLE AND NOT QUANTIFIABLE. WHAT REMAINS IS THAT THE STATES RESPONSIBLE FOR THE SLAVE TRADE MUST REALIZE THAT IT IS THEIR DUTY TO HELP THE COUNTRIES THEY CONTRIBUTED TO PLUNGING INTO POVERTY. BUT TO WANT TO PUT A PRICE ON THIS CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY… THAT’S A DIFFERENT MATTER.”

The issue of reparations for the descendants of Black slaves remains a contentious and controversial subject. The Slave Compensation Act, which left former slaves without support, highlights a major historical injustice. To move toward a more equitable society, it is crucial to acknowledge these past wrongs and engage in serious discussions about how to rectify them.

Bibliography

- The Economics of Emancipation: Jamaica & Barbados, 1823-1843 / Kathleen Mary Butler

- Britain’s Black Debt: Reparations for Caribbean Slavery and Native Genocide / Hilary McD. Beckles

Summary

Footnotes

- British West Indies: A group of British colonies located in the Caribbean Sea, including islands like Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, and others. These colonies played a crucial role in the British economy due to the production of sugar, tobacco, and cotton, which heavily exploited the labor of African slaves until the abolition of slavery in 1838. ↩︎

- Sir John Gladstone, 1st Baronet (1764-1851): A wealthy British landowner and merchant, known for his involvement in the slave trade and for being heavily compensated after the abolition of slavery. He was also the father of William Ewart Gladstone, who later became the British Prime Minister. ↩︎

- Demerara Rebellion (1823): A major slave uprising in British Guiana, led by Jack Gladstone. Approximately 10,000 slaves revolted against oppressive living conditions, but the rebellion was brutally suppressed by colonial authorities. This event garnered significant international attention and contributed to the abolitionist movements in Britain. ↩︎

- Jack Gladstone: Leader of the 1823 Demerara slave rebellion in British Guiana. Son of the slave Quamina Gladstone, he played a central role in one of the most significant uprisings against slavery in the British Caribbean. ↩︎

- Slave Compensation Act (1837): A law passed by the British Parliament providing compensation to slave owners following the abolition of slavery. It allocated £20 million to compensate slave owners for their economic losses, with no compensation given to the freed slaves. ↩︎

- Slavery Abolition Act (1833): A law passed by the British Parliament that abolished slavery in most of the British Empire, marking a crucial milestone in the history of abolition. This law immediately freed children under six years old and established a period of apprenticeship for other slaves before their full liberation. ↩︎