A dive into the intricacies of Françafrique with the revelations of Robert Bourgi. Nofi explores the covert financing of French politics by African regimes, a complex system that continues to shape Franco-African relations even in the face of current reforms and geopolitical tensions.

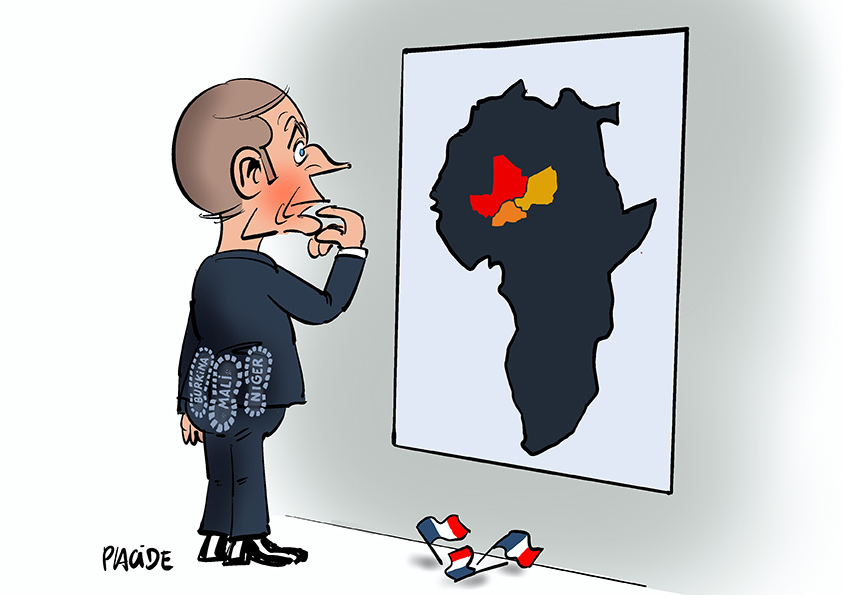

In 2024, Françafrique continues to thrive in the shadows of successive French governments, despite repeated promises of a break. A sprawling system of covert financing, neo-colonial relations, and corruption still permeates the workings of Franco-African politics. This dark network, barely hidden behind diplomatic façades, shapes the future of millions of African citizens while keeping a handful of elites in power. Far from being a mere historical relic, Françafrique is a silent cancer, fed by the insatiable appetite for African resources and the ambitions of French leaders.

The legacy of Françafrique, built on decades of complicity between French leaders and African presidents, has been meticulously documented by journalists and researchers. François-Xavier Verschave, author of Françafrique: The Longest Scandal of the Republic, was one of the first to denounce this incestuous relationship:

“FRANÇAFRIQUE IS A NEOLOGISM BORN TO DENOUNCE THE NEO-COLONIAL ATTITUDE THAT FRANCE MAINTAINS TOWARDS ITS FORMER COLONIES, A NETWORK OF ECONOMIC, POLITICAL, AND MILITARY INTERESTS THAT BETRAY DEMOCRATIC IDEALS.”

This doctrine, which has guided Franco-African relations since the independence of French colonies, rests on a brutal reality: France, although retired from its colonial lands, continues to pull the strings of power through corrupt alliances and secret financing.ue retraitée de ses terres coloniales, continue de tirer les ficelles du pouvoir à travers des alliances corrompues et des financements secrets.

Suitcases of cash and covert financing

Robert Bourgi, lawyer and influential advisor, one of the major players in Françafrique, recently revealed in his book My Life in France-Africa the details of a system where suitcases full of cash regularly passed between Africa and France.

“I CARRIED CASH IN SUITCASES, ASTRONOMICAL AMOUNTS THAT FINANCED ELECTORAL CAMPAIGNS. THIS WAS THE REALITY OF FRANÇAFRIQUE.”

These funds, often taken from the wealth of African countries, notably oil and uranium, were used to buy the influence of French politicians, but also to maintain dictatorial regimes in Africa.

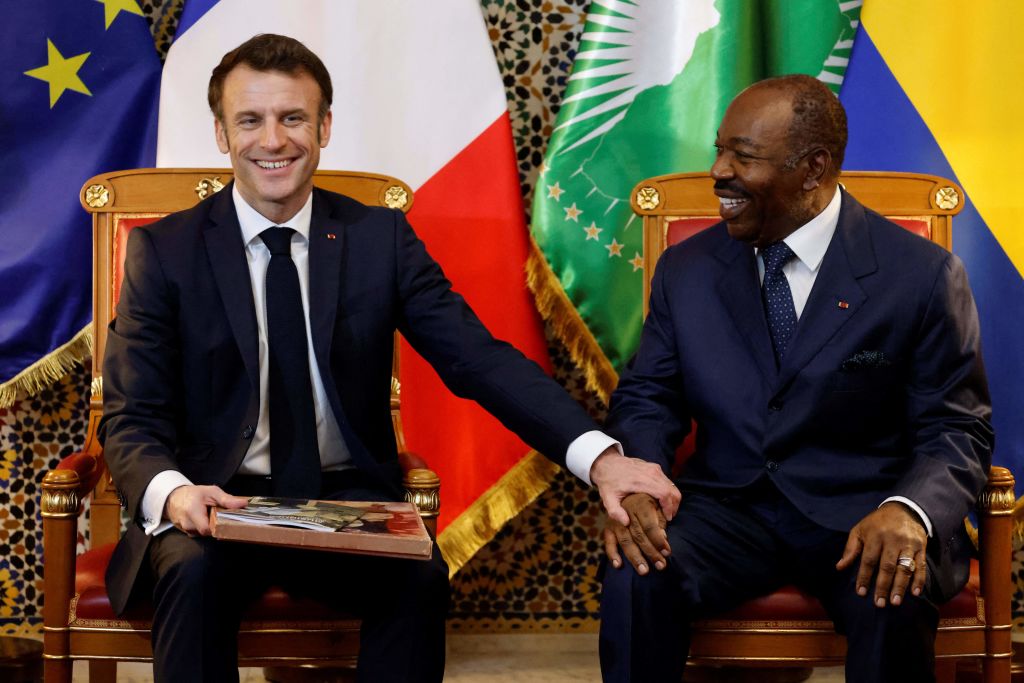

One of the most emblematic examples remains the Elf affair, revealed in the 1990s, which showed the extent of Franco-African corruption. The Elf trial exposed that the leaders of Elf Aquitaine, the oil giant, paid secret commissions to African heads of state, such as Omar Bongo of Gabon, in exchange for lucrative oil contracts. Patrick Pesnot, in The Secrets of Françafrique, explains:

“THE ELF TRIAL REVEALED THE EXTENT OF ORGANIZED CORRUPTION ON AN INTERNATIONAL SCALE, WHERE AFRICAN DICTATORS RECEIVED COMMISSIONS IN EXCHANGE FOR ACCESS TO NATURAL RESOURCES.”

The guilty silence of the Republic

Former French President Jacques Chirac, a symbol of this tradition of covert financing, was accused of maintaining close financial ties with African regimes to fund his electoral campaigns. Bourgi claims to have regularly delivered suitcases of money to Chirac, coming from African presidents such as Omar Bongo (Gabon), Blaise Compaoré (Burkina Faso), and Denis Sassou Nguesso (Congo).

“THE PRESIDENT ASKED ME TO BRING HIM THESE FUNDS. I NEVER DELIVERED LESS THAN A MILLION DOLLARS.”

These practices helped maintain strong ties of influence, making these African heads of state beholden to French power.

Historian Jean-Pierre Bat emphasizes that:

“THESE FINANCIAL FLOWS DID NOT JUST CONCERN THE FINANCING OF FRENCH ELECTORAL CAMPAIGNS. THEY ALSO SERVED TO MAINTAIN AN ECONOMIC DEPENDENCE NETWORK WHERE FRANCE ENSURED ACCESS TO STRATEGIC AFRICAN RESOURCES.”

The failure of democratic revolutions

Throughout recent history, attempts at democratization in Francophone Africa have often been stifled by this invisible grip. In 2010, Ivorian President Laurent Gbagbo was ousted after contesting the election results against Alassane Ouattara, supported by the international community, particularly France. Robert Bourgi claims that Nicolas Sarkozy, then President of France, gave the order to overthrow Gbagbo.

“SARKOZY TOLD ME: ‘I’M GOING TO VITRIFY HIM.’ IT WAS A BRUTAL DEMONSTRATION OF HOW FRANCE HANDLES ITS FORMER AFRICAN ALLIES.”

This statement highlights France’s constant interference in the internal affairs of African countries. Cette déclaration met en lumière l’ingérence constante de la France dans les affaires intérieures des pays africains.

Oil and uranium: the lifeblood of the war

If Françafrique persists, it is largely due to France’s strategic economic interests in Africa. Oil, notably in Gabon and Angola, as well as uranium in Niger, are vital resources for French industry. Jacques Foccart, the father of Françafrique, had already emphasized the importance of these resources for the survival of French power:

“OIL, URANIUM, RAW MATERIALS, THESE ARE THE KEYS THAT ALLOW FRANCE TO MAINTAIN ITS INFLUENCE IN AFRICA.”

Companies like Areva (now Orano) have long maintained close ties with authoritarian African regimes, particularly in Niger, where uranium exploitation is essential for France’s nuclear program. Maintaining regimes favorable to these strategic interests remains a priority for Paris.

A system in mutation?

For several decades, each French president, from François Hollande to Emmanuel Macron, has promised the end of Françafrique. Yet, networks of influence persist. In 2019, Macron announced his desire to “rebuild” Franco-African relations, acknowledging the crimes committed during colonization, but the facts on the ground reveal a different reality.

Historian Antoine Glaser, author of Arrogant as a Frenchman in Africa, explains:

“FRANCE HAS NEVER REALLY ACCEPTED TO GIVE UP ITS INFLUENCE IN AFRICA. BEYOND OFFICIAL SPEECHES, MILITARY AGREEMENTS, AND CLOSE ECONOMIC TIES HAVE BEEN MAINTAINED, ESPECIALLY IN STRATEGIC SECTORS LIKE OIL AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS.”

As economic and political relations transform with the arrival of new actors such as China and Russia, France seems to be losing ground on the African continent. But Françafrique, in new forms, continues to survive. The suitcases of cash may no longer be as frequent, but economic interests remain, as do dubious alliances.

The eternal shadow of Françafrique

Far from disappearing, Françafrique has reinvented itself. It persists, fueled by a global economic system that favors the exploitation of African resources at the expense of local development. Presidents come and go, dictators too, but the system remains. In the corridors of African palaces and at the Elysée, the shadow of Françafrique continues to haunt political decisions.

The challenge for France remains reconciling its colonial past with a future based on equal and transparent partnerships. But as long as African resources continue to fuel the French economy, this page will never truly be turned.

Notes and references

- Verschave, François-Xavier. Françafrique: The Longest Scandal of the Republic, Stock, 1998.

- Bourgi, Robert. My Life in France-Africa, Max Milo, 2017.

- Pesnot, Patrick. The Secrets of Françafrique, Flammarion, 2014.

- Bat, Jean-Pierre. The Foccart Syndrome: French Politics in Africa, from 1959 to Today, Gallimard, 2012.

- Glaser, Antoine. Arrogant as a Frenchman in Africa, Fayard, 2016.

- Gould, Stephen Jay. The Mismeasure of Man, W.W. Norton & Company, 1981.

- Elf Trial. Le Monde, November 7, 2003.

- UNESCO. The Slave Route, Report of the International Scientific Committee, 2022.

- Glaser, Antoine. Africafrance: When African Leaders Become the Masters of the Game, Fayard, 2014.

- Tshiyembe, Mwayila. The Postcolonial State in Africa: Rethinking Democracy and Sovereignty in the Light of Françafrique, Karthala, 2010.