An iconic pharaoh of ancient Egypt, Akhenaten, often considered the pioneer of monotheism, remains a fascinating figure for his radical religious reform and unconventional art. Born as Amenhotep IV, he ascended the throne in the 14th century BCE, inheriting the prosperous reign of his father, Amenhotep III. Akhenaten profoundly impacted history with his attempt to overturn the established religious system in favor of a singular worship dedicated to Aten, symbolized by the solar disk. His vision of divine and royal power continues to captivate historians and archaeologists, nearly 3,300 years after his death.

Akhenaten’s origins and youth

Akhenaten, born under the name Amenhotep (or Amenophis in Greek), was born into one of the most powerful pharaonic dynasties of Egypt. He was the son of Amenhotep III, a pharaoh who ruled over one of Egypt’s most prosperous empires, and Queen Tiye, his principal wife. Born probably in the latter half of the 14th century BCE, Amenhotep IV, who would become Akhenaten, grew up in a deeply religious and intellectual environment, where the clergy of Amun played a prominent role.

Amenhotep III, Akhenaten’s father

Amenhotep III, also known as Amenophis III, was one of the most iconic pharaohs of the 18th dynasty. Under his reign, Egypt experienced a period of political stability, territorial expansion, and economic prosperity. He fathered at least six children with Queen Tiye, seeing his eldest son, Thutmose, as his presumed heir. However, the premature death of Thutmose propelled the young Amenhotep IV into the spotlight as the future pharaoh. It was after this loss that the destiny of young Amenhotep began to unfold toward his ascent to power and the implementation of reforms that would shake ancient Egypt.

The disappeared heir: Prince Thutmose

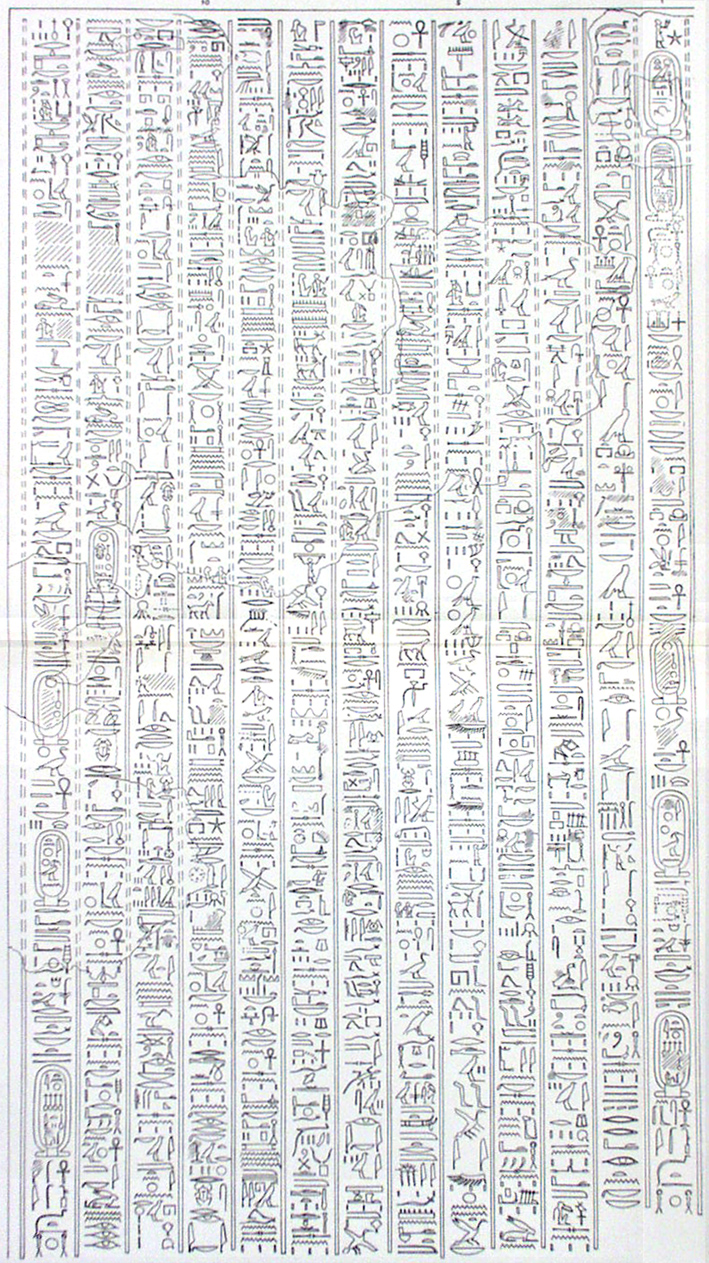

Before the death of his elder brother, Amenhotep IV was not expected to rule. Prince Thutmose, the natural heir to Amenhotep III, was prepared for succession. As the eldest, he received the rigorous education reserved for future kings: mastering hieroglyphics, mathematics, and military skills. However, his death around the 29th year of Amenhotep III’s reign thrust Amenhotep IV into the unexpected role of presumptive heir.

Pharaoh training

Like any young Egyptian prince, Amenhotep IV was likely trained by palace tutors who taught him sciences, literature, and the art of war. It was only later that his religious orientations began to stand out. However, the military and diplomatic training he received, combined with traditional religious education, made him an educated ruler, albeit with a mind radically inclined toward reform.

Ascension to the throne and transition to Aten worship

Amenhotep IV ascended the Egyptian throne upon his father’s death around 1352 BCE. Early depictions of Amenhotep IV show him in traditional postures, with relatively conventional features. He took the coronation name Neferkheperure Waenre, meaning “Perfect are the manifestations of Re, the One of Re.” In accordance with tradition, he organized his father’s funeral and began to honor the dynastic gods, notably Amun-Re.

However, very early in his reign, Amenhotep IV expressed growing interest in Aten, the god represented by a solar disk. Aten was not unknown to Egyptians but had held a secondary place in the Egyptian pantheon. The pharaoh decided to elevate Aten above other deities, presenting him as the sole creative force behind all life on Earth. It was at this point that the religious revolution began.

The rise of Aten

By the third year of his reign, Amenhotep IV intensified his promotion of Aten worship. He declared himself the “first priest” of this god and had several temples erected in his honor, including one in Karnak, at the heart of Amun-Re’s domain. However, he continued to appear under the protection of Amun, marking a phase of transition between the old and new worship.

In the fourth year of his reign, the pharaoh introduced a major innovation: Aten’s name was inscribed within a cartouche, a privilege generally reserved for royal names. This marked the beginning of a new era in which Aten was no longer just one god among others but the only deity deserving official worship.

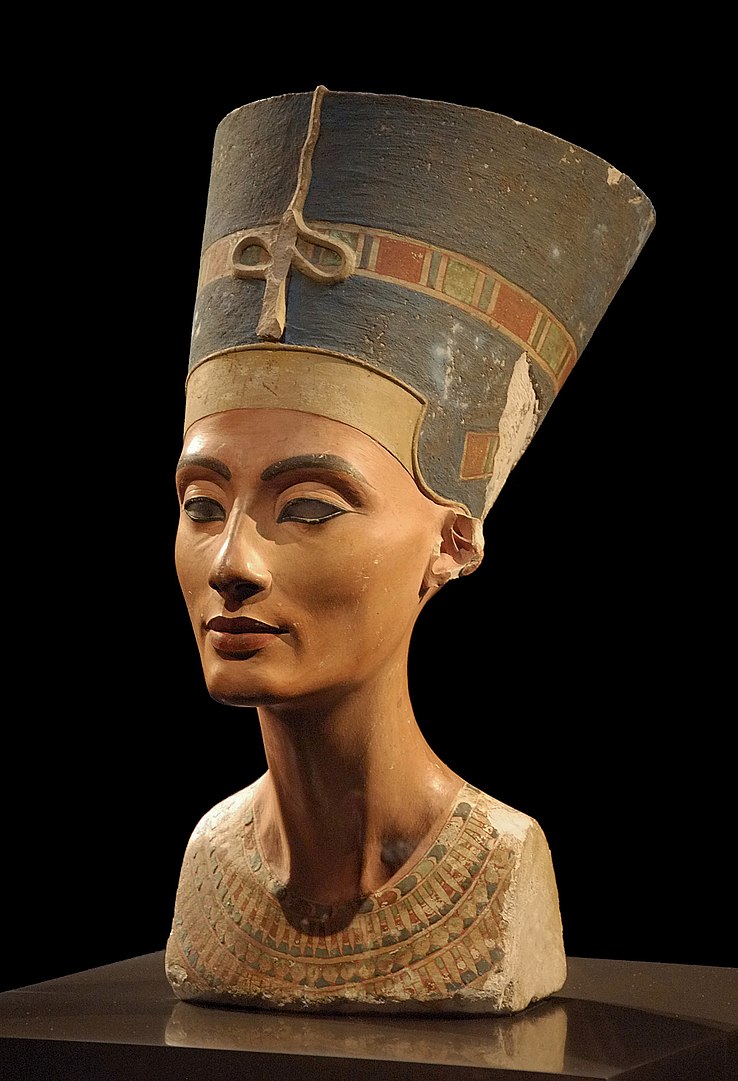

Nefertiti, the Great Royal Wife

Shortly after the start of this religious transition, another iconic figure emerged: Nefertiti, Amenhotep IV’s great royal wife. Her legendary beauty and role alongside the pharaoh are celebrated in numerous depictions. The royal couple was often portrayed together in scenes of worship before Aten, emphasizing the sacred and central nature of this union in the new religion. This union produced at least six daughters, three of whom were born between the fourth and seventh years of Akhenaten’s reign. Nefertiti also played a major political role, participating in the affairs of the kingdom alongside her husband.

The new name: Akhenaten

In the fifth year of his reign, Amenhotep IV made a radical decision. He officially changed his name to Akhenaten, meaning “One who is useful to Aten,” symbolizing his exclusive devotion to this solar deity. He also announced the construction of a new capital, Akhetaten, located halfway between Thebes and Memphis, on a site known today as Tell el-Amarna. This choice marked a complete break with the old capital, Thebes, home to the Amun clergy, who refused to adopt the new religion. Akhetaten, the “City of the Horizon of Aten,” quickly became the religious and political center of Egypt.

A new form of art: Amarna style

With the founding of Akhetaten, Akhenaten also introduced a new aesthetic in Egyptian art. This period, known as Amarna art, is characterized by more naturalistic representations of figures. Scenes depicting the pharaoh and his family broke away from the rigid representations of traditional Egyptian art. Akhenaten is often depicted with distinctive physical features: an elongated face, wide hips, and a nearly androgynous body. Some theories suggest these representations could reflect an actual genetic disorder, although this remains debated.

This revolutionary art also portrayed more intimate moments, notably scenes of tenderness between Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their children, breaking from the formal depictions of royal figures in traditional art.

The Aten cult and the suppression of other deities

From the seventh year of his reign onward, Akhenaten intensified the repression of the old gods. Amun’s name was systematically erased from monuments, and temples dedicated to other deities were closed or repurposed for the worship of Aten. However, this campaign of suppression faced considerable resistance, particularly from the powerful Theban clergy. Despite these efforts, Aten worship never gained widespread acceptance among the Egyptian population, which remained deeply attached to its traditional deities.

Foreign policy under Akhenaten

Internationally, Akhenaten’s reign coincided with a period of instability. The Egyptian Empire, which dominated Syria-Palestine, saw its influence wane in favor of the Hittites, a rising empire. Thanks to letters written in Akkadian, found in Tell el-Amarna, we know that Akhenaten maintained diplomatic relations with the great powers of the time, including the Mitanni, Assyrians, and Babylonians. However, his relations with his Syrian and Canaanite vassals were strained, as they repeatedly rebelled against Egyptian authority.

The final years and death of Akhenaten

The final years of Akhenaten’s reign were marked by personal and political hardships. On a personal level, the pharaoh lost several daughters and his mother, Queen Tiye, during a possible epidemic. Externally, Egypt gradually lost its grip on its territories in Asia, threatened by Hittite expansion. Akhenaten attempted to maintain a buffer state, Amurru, but tensions with the Hittites and the rebellion of Qadesh further weakened Egypt.

Akhenaten died after seventeen years of reign, leaving behind a weakened empire and an unfinished revolution. His son, Tutankhaten, later renamed Tutankhamun, quickly returned to the worship of Amun, erasing nearly all traces of his father’s reign.

The legacy of Akhenaten

Akhenaten’s legacy is complex. Although much of his reign was erased from official records, he remains a fascinating figure in Egyptian history. His attempt to establish a monotheistic cult has often been compared to later religious movements, including Judaism, Islam, and Christianity. His Hymn to Aten, a major religious text from this period, is sometimes seen as one of the earliest expressions of monotheism.

While his cult of Aten did not survive his death, Akhenaten left his mark on history through his audacity and desire for reform, illustrating how inseparable religion and politics were in ancient Egypt. To this day, his reign continues to spark debates about religion, art, and power in antiquity.

Summary

References:

- Théophile Obenga (1990), La philosophie africaine de la période pharaonique : 2780-330 avant notre ère, Paris: l’Harmattan.

- Marc Gabolde (2005), Akhenaten: From Mystery to Light, Paris: Gallimard.

- Fabien Hertier (2012), “Two Mentions of Akhenaten’s Prenomen in a 10th Century Byzantine Encyclopedia,” ENIM 5, pp. 115-117.

- Dimitri Laboury (2010), Akhenaten, Paris: Pygmalion.