This article inaugurates a series dedicated to exploring African cultural survivals in Caribbean society, shedding light on the profound impact of African heritage on the physical and social behavior of Caribbean people. Through a detailed analysis of their daily gestures and codes of politeness, we delve into the rich cultural tapestry of the African diaspora, illustrating how these traditions endure and transform in the French Caribbean.

Journey through Caribbean cultural heritage: an exploration of African roots

Nofi invites you, through a series of articles, to dive into the depths of Caribbean culture with a captivating piece from the emblematic work directed by Jean-Luc Bonniol1, Historial antillais. Tome I. Guadeloupe et Martinique. Des îles aux hommes. This exploration, spanning pages 275 to 289 and published by Dajani Éditions in 1981, is a deep reflection based on Huguette Bellemare2‘s analysis titled Survivances africaines.

Join us on this enriching journey, revealing the nuances of the physical and social behavior of Caribbean people, a vibrant testament to the indelible influence of African heritage on the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique.

Physical (African) and social behavior of Caribbean people

Physical attitudes

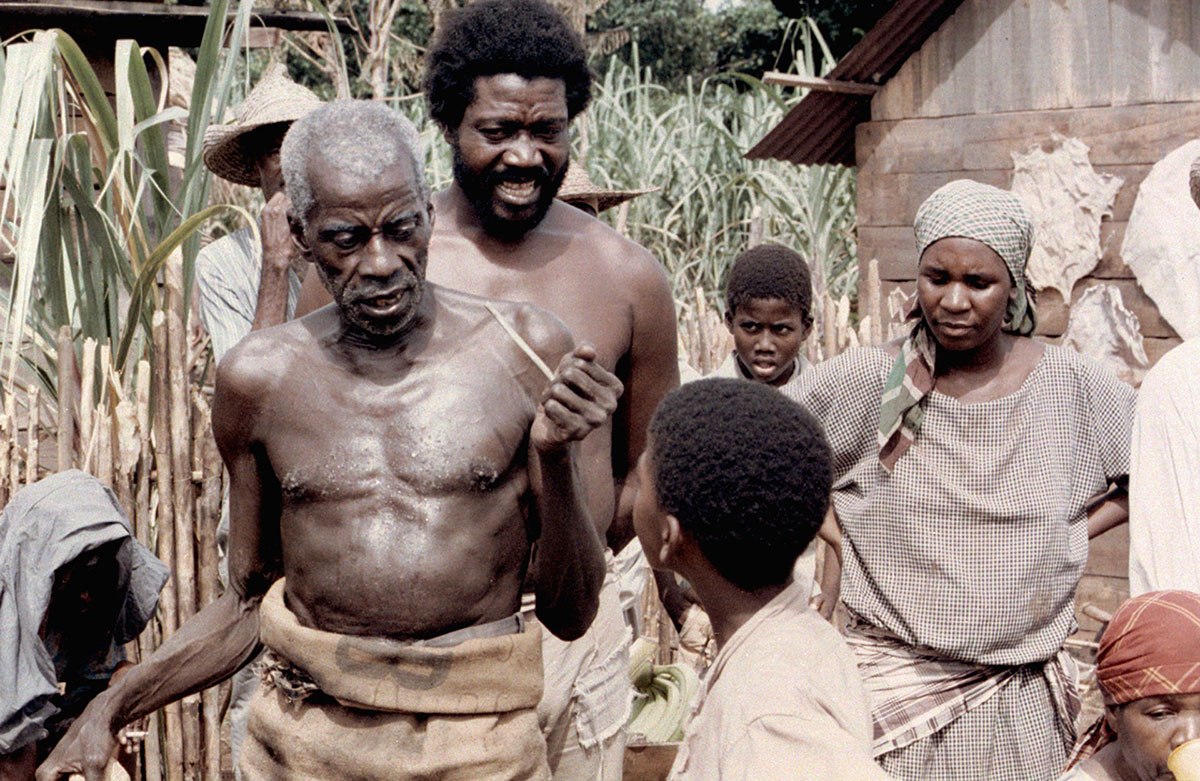

In the everyday gestures of Caribbean people, African origins can be seen.

As described by Father Du Tertre3, Caribbean women still carry their children on their hips, just like the first African slaves did. Additionally, the widespread habit of carrying children “à dada” (astride on the back) seems to be a somewhat diluted survival of the traditional African method of carrying children, though the cloth (pagne) has been lost along the way.

Like in Africa, Caribbean people also carry light objects on the flat of their upturned hands and heavier loads on their heads (note the role women play in maintaining these ancient gestures).

It should be noted that these deeply ingrained physical behaviors are independent of physical type. At most, they may be linked to social class. A Caribbean woman whose socio-professional status involves the need to transport loads will carry them in this manner, regardless of her ethnic origin. This shows that culture is primarily learned and not necessarily tied to physical or racial type.

Social Behavior

In precolonial West African societies, individuals were part of a complex network of social and political relations. These African social systems could not coexist with the slavery system in America. However, African traits persist in the social behavior of Caribbean people, especially in their interactions with others.

Etiquette

There is, among the Caribbean people, and more generally among Black people in the Americas, a code of politeness that is strictly followed.

In Martinique, some elderly individuals still turn their faces away when they laugh; the gesture of covering the mouth with the hand in this situation is even more common and is still seen among rural youth. According to Herskovits4, who observed the same behaviors in the United States, these are attitudes of African origin.

When two Caribbean individuals meet, their exchange takes the form of an institutionalized dialogue, meaning that while one speaks, the other ritually agrees with responses like, “Yes, Han-Han, Ebin, ou ka conprann…“

Moreover, this behavior occurs even in situations where someone from another culture (for instance, Western) would not think to agree. Thus, during a lecture, a conference, or an explanation given by a guide, for example, such exchanges can be punctuated with “yes sir“—especially when the audience is of modest origin.

This attitude is also observed among Black people in the United States and has even been institutionalized by Black pastors (Oh yes, Oh no…).

It should be connected to the African conception of politeness, where passively listening to another’s words is considered impolite.

Finally, an important chapter in Caribbean politeness, and even in its morality, is the respect due to elders. We will address this point later.

Forms of cooperation

Solidarity is an important element of African ethics, cementing the group and manifesting in cooperative habits in the economic domain.

This practice of solidarity could only be reinforced by slavery: in fact, the organization of labor on plantations5 likely helped maintain habits of communal labor. Furthermore, slaves, left to themselves outside of the required tasks, had to organize their lives and survival, which they could only achieve through mutual help. Even today, African solidarity practices persist in the rural masses that are still imperfectly integrated into the modern economy.

Cooperative labor

In rural areas of the Caribbean, to accomplish an important task (clearing and tilling a field, but also building a house or grating cassava), one rarely resorts to paid labor6. Instead, an “assaut” (assault) is organized – the “assaut-tè,” for instance: neighbors gather on the land to be cleared or plowed. The women serve drinks and prepare food – drinks and food provided by the landowner; the men encourage each other with songs, jokes, and challenges… In the past, the owner even ensured the presence of an orchestra or at least a drum player:

“… ON THE CHOSEN DAY, THEY ALL COME WITH HOES, MACHETES, PICKS, SPADES. ONE ONLY HAS TO PREPARE THE POT OF VEGETABLES (AND SALTED PORK), THE BARREL OF RUM, AND THE DRUM.” Zobel7 : Diab’là, p. 76-79. Nouvelle Édition Latine.

Zobel: Diab’là, pp. 76-79. Nouvelle Édition Latine. This form of labor organization is found in Guadeloupe (called “convoi”), in Trinidad (“Gayap”), in Haiti (famously known as “coumbite” described by Roumain), in the United States, and more generally, wherever there are strong concentrations of Black people across the American continent.

“HOWEVER, THE ASSAUT IS EXPENSIVE, REVERT TELLS US, BECAUSE OF THE RECEPTION THAT ACCOMPANIES IT. NOWADAYS, PEOPLE INCREASINGLY RELY ON ‘HELPING HANDS’ EXCHANGED BETWEEN NEIGHBORS, ON A GIVE-AND-TAKE BASIS.”

Bastide notes a similar evolution in Haiti, where collective work has shifted from associations (exchanging labor for money or food) to the “ron”—derived from the French “ronde” (work exchanged for work). Bastide also suggests that collective work in Haiti was linked to the extended family (Laku), which originated in Africa.

While acknowledging the importance of collective labor for Black societies, various authors have questioned whether its origin is exclusively African. Bastide notes that these practices exist in traditional peasant societies in Europe, which he calls “folk societies.”

However, Herskovits already observed that while cooperative labor did exist among early American colonists (“the pioneers”), it was certainly not practiced in regions with slaves, as they were there, by definition, to perform all tasks, from the lightest to the heaviest. Thus, he believes that these cooperative labor traditions are inherited from West Africa, particularly from the Dahomean Dopkwe.

What remains of these customs today?

What remains of work done to music are work songs preserved in our folklore.

In economically disadvantaged communities, the practice of mutual help continues, especially to build small houses in a single day (often on Sundays) and secretly from the authorities, constructing the small shacks that make up the slums of the suburbs.

Mutual aid societies

Everyone is familiar with the importance of secret societies in West Africa, but much less has been said about the numerous other associations that have played a considerable role in African social structures.

Caribbean people have particularly inherited the “associative” nature of their African ancestors. Moreover, as we mentioned, slavery and the post-slavery society, having left the Black masses excluded from economic (banks…) and social circuits (insurance, mutual funds…), forced these populations to organize their own mutual aid.

For all these reasons, mutual aid societies have developed significantly in the Caribbean8. Examples include L’Humanité Solidaire, Vers La Lumière, La Fraternité, L’Espoir, and others. These societies aim to provide reimbursement for medical and pharmaceutical expenses in case of illness and financial assistance to the families of the deceased, particularly to help them cope with funeral expenses.

However, according to Bangou, “aside from these material advantages, they primarily fulfill a need for Caribbean people to come together and organize regular festivities.” In this sense, they may have initially played a compensatory role for Black individuals who were first excluded from the broader society.

Finally, in the domain of cooperation, we should mention the institution that the Yoruba call esusu and which can be found in Trinidad under the name susu:

“A fixed number of people agree to deposit a certain amount of money each week with one of their members; the latter asks for no compensation for the services rendered… They commit to handing over the accumulated funds of the week to another member, and this continues until all have been able to realize something with these contributions… This system allows a person, without needing to save systematically, to finance personal projects without having the means.” — Melville Herskovits, 1966: The Negro Heritage: Myth and Reality, Présence Africaine

This institution can be found under the same name (sousou) and functioning in the same way with the same goals in Martinique, where it is still practiced today despite urbanization and the Westernization of lifestyles, even among the more acculturated layers of society—the petite bourgeoisie.

Summary

Footnotes

- Jean-Luc Bonniol is a renowned French anthropologist and researcher specializing in the study of Caribbean and Guyanese societies. He is known for his in-depth work on identity, memory, and cultural mixing in these regions. His research and publications, notably in the work Historial Antillais. Volume I. Guadeloupe and Martinique. From Islands to People, provide valuable perspectives on the history and cultural dynamics of Caribbean societies. ↩︎

- Huguette Bellemare is a researcher and author who has explored the cultural and social aspects of Caribbean communities. She is notably recognized for her article Survivances Africaines (African Survivals), which examines the enduring African influences in the physical and social behaviors of Caribbean people. Her work sheds light on the depth and complexity of African cultural legacies in the Caribbean, contributing to a better understanding of identity and cultural practices in the region. ↩︎

- Father Jean-Baptiste Du Tertre was a 17th-century French Dominican missionary and naturalist. He is known for his detailed writings on the Caribbean, including his historical and geographical account of the islands of America, where he described the fauna, flora, and societies of the Caribbean islands, including the customs and practices of the indigenous peoples and African slaves. His works provide a valuable glimpse into life in the Caribbean during the colonial period. ↩︎

- Melville J. Herskovits was an American anthropologist renowned for his pioneering research on African culture and its influences in the New World, particularly in the Caribbean and America. His works, including The Myth of the Negro Past, are fundamental for understanding the persistence and transformation of African cultural practices in African diasporas and helped shape the field of cultural anthropology. ↩︎

- Work on plantations: The cutting of crops, in particular, was done by teams of workers (men, women, and often children), with each person assigned a task complementary to the others. ↩︎

- Money circulation in rural society: In traditional rural society, at least, money circulated very little, if at all. The economy was based on the exchange of services and gifts. Money only appeared during major, often unfortunate, events, such as accidents or illnesses affecting a relative or neighbor (again reflecting a sense of solidarity). Even then, it wasn’t always kept in liquid form. Savings often took the form of a woman’s jewelry or livestock (pigs, cattle) that could be sold or slaughtered in times of hardship. (See Zobel’s novels on this subject). ↩︎

- Joseph Zobel was a celebrated Martinican writer, best known for his novel La Rue Cases-Nègres, which offers an intimate look at life on the plantations in Martinique during the 1930s. His work is appreciated for its authentic representation of Caribbean culture, highlighting social challenges and community dynamics of the time. Zobel is often cited for his contribution to Caribbean literature and his commitment to representing the lives and perspectives of Caribbean people in his writing. ↩︎

- Mutual Aid Societies: In 1951, the Mutual Aid Federation of Martinique grouped 66 associations with nearly 60,000 members, and in 1952, the Guadeloupe Federation had over 70 societies gathering around 40,000 people.” (Leiris, Contacts de Civilisation, p. 62). ↩︎